- 1 Methylphenidate – A Guide to Buying Safely and Effectively

- 2 Why Choose Methylphenidate

- 3 Tips for Purchasing Methylphenidate Securely

- 4 The Convenience of Methylphenidate Shopping

- 5 Make Your Purchase Count

- 6 Summary

- 7 History and culture

- 8 Chemistry

- 9 Pharmacology

- 10 Subjective effects

- 11 Toxicity

- 12 Legal status

- 13 FAQ

- 13.1 1. What is Methylphenidate?

- 13.2 2. How does Methylphenidate work?

- 13.3 3. What are the common brand names for Methylphenidate?

- 13.4 4. What are the common uses for Methylphenidate?

- 13.5 5. Is Methylphenidate safe to use?

- 13.6 6. What are the potential side effects of Methylphenidate?

- 13.7 7. Can Methylphenidate be abused or addictive?

- 13.8 8. How should Methylphenidate be taken?

- 13.9 9. Can Methylphenidate be used by children and adults?

- 13.10 10. Are there any drug interactions with Methylphenidate?

- 13.11 11. Can Methylphenidate be stopped suddenly?

- 13.12 12. Is it safe to drive or operate machinery while taking Methylphenidate?

- 13.13 13. Can Methylphenidate be used for purposes other than ADHD or narcolepsy?

- 13.14 14. Is Methylphenidate available over-the-counter (OTC)?

- 14 References

Methylphenidate – A Guide to Buying Safely and Effectively

When choosing a stimulant like Methylphenidate, understanding reliable purchasing methods, safety measures, and the benefits it offers is critical. Whether you’re looking to buy Methylphenidate online, find Ritalin for sale in the USA or Canada, or explore Methylphenidate shop options globally, informed decisions ensure a better experience.

Why Choose Methylphenidate

Methylphenidate has become a preferred option due to its versatility and effectiveness. It appeals to individuals seeking a trusted stimulant for research purposes or personal use. With global availability in markets offering Ritalin buy services, finding a reliable supplier is now easier than ever. The ability to purchase MPH in a variety of forms ensures that consumer needs are met conveniently.

For those looking to buy Methylphenidate USA or Methylphenidate online Canada, platforms offering Methylphenidate for sale provide access to trusted solutions. With competitive pricing and transparent product descriptions, these vendors cater to both local and international buyers.

Tips for Purchasing Methylphenidate Securely

Making a confident and safe purchase requires following some essential guidelines. If you’re planning to order Methylphenidate online, consider these tips for a smooth process:

- Research Trusted Vendors

Sellers specializing in Methylphenidate research chemicals should have positive reviews and transparent policies. Opt for Methylphenidate buy online options with verified authenticity.

- Clarify Product Availability

Whether you’re looking for Methylphenidate powder, Methylphenidate usa suppliers, or options to buy Methylphenidate bath salts, confirm availability and specifications upfront.

- Secure Payment Options

Reliable vendors provide secure payment systems, such as credit card payments, ensuring a safer and more convenient checkout experience.

- Global Shipping Options

Whether you’re based in the USA, Australia, or elsewhere, prioritize vendors offering discreet packaging and efficient delivery to guarantee your product arrives securely.

The Convenience of Methylphenidate Shopping

Online platforms offering Methylphenidate for sale have revolutionized access to this sought-after stimulant. With easy-to-navigate Methylphenidate shop features, international buyers can explore options to buy Methylphenidate Australia, Methylphenidate Canada, or even source MPD China. This convenience ensures that regardless of your location, high-quality products are within reach.

From finding Methylphenidate vendors with clear return policies to platforms specializing in order Methylphenidate online, today’s market provides numerous opportunities for consumers to shop with confidence.

Make Your Purchase Count

Whether you’re searching for Methylphenidate buy online USA or researching the best Methylphenidate usa suppliers, taking the time to find trusted vendors ensures both safety and satisfaction. Start exploring now and experience the benefits of purchasing Methylphenidate through reliable sources.

Summary

Methylphenidate, known by various names such as MPH, MPD, Ritalin, Concerta, and Methylin, belongs to the classical stimulant category within the phenidate class. Within this family of stimulants, one can find related compounds like ethylphenidate and isopropylphenidate. The primary mode of action of Methylphenidate involves elevating the levels of neurotransmitters dopamine and norepinephrine in the brain.

This substance was initially synthesized in 1944 and gained approval for medical use in the United States in 1955. The Swiss company CIBA, which has since become Novartis, was the original distributor. Methylphenidate is primarily sanctioned for the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and narcolepsy. Notably, it is also employed by students, both with and without ADHD, as a cognitive enhancer and study aid.

The subjective effects attributed to Methylphenidate encompass stimulation, improved focus, enhanced motivation, heightened libido, reduced appetite, and feelings of euphoria. Typically administered orally, it can also be taken through insufflation or rectal administration. Its effects are often likened to those of amphetamine, albeit with less pronounced euphoria and generally lower recreational value. Some users additionally report a more pronounced comedown compared to amphetamine.

Methylphenidate does pose a moderate risk of abuse. Prolonged use, characterized by high doses and repeated administration, can lead to compulsive redosing, escalating tolerance, and psychological dependence. Therefore, responsible use and the implementation of harm reduction strategies are strongly recommended for individuals considering the use of this substance.

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| showIUPAC name | |

| CAS Number | 20748-11-2 |

| PubChem CID | 4158 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 7236 |

| DrugBank | DB00422 |

| ChemSpider | 4015 |

| UNII | 207ZZ9QZ49 |

| KEGG | D04999 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:6887 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL796 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID5023299 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.662 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C14H19NO2 |

| Molar mass | 233.311 g·mol−1 |

History and culture

Methylphenidate received its first approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) back in 1955, primarily intended for the treatment of a condition then referred to as “hyperactivity.” Although it was prescribed to patients as early as the 1960s, its widespread use only gained momentum in the 1990s, coinciding with the broader recognition and acceptance of ADHD as a legitimate medical diagnosis.

In 2013, there was a notable surge in the global consumption of methylphenidate, with an estimated 66% increase compared to the previous year, reflecting a growing reliance on this medication. By 2019, it had secured a position as the 51st most frequently prescribed medicine in the United States, with over 14 million prescriptions written annually. Notably, generic versions of this medication are readily available, contributing to its accessibility and widespread use.

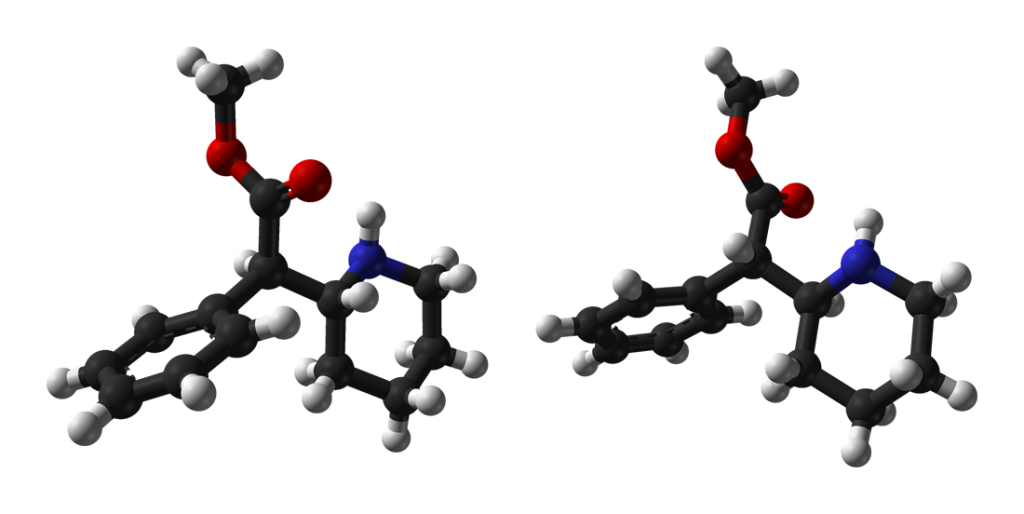

Chemistry

Methylphenidate belongs to the synthetic molecules falling within the substituted phenethylamine and substituted phenidate classes. Its chemical structure comprises a phenethylamine core characterized by a phenyl ring linked to an amino (-NH2) group via an ethyl chain.

Structurally akin to amphetamine, Methylphenidate features a substitution at the Rα position, forming a piperidine ring culminating at the terminal amine of the phenethylamine chain. Additionally, it incorporates a methyl acetate group bound to its Rβ place.

Within chiral compounds, Methylphenidate is presumed to exist as a racemic mixture. However, an enantiopure variant is also accessible as a pharmaceutical product; this dextrorotary enantiopure form is commonly known as “dexmethylphenidate” and is frequently marketed under the names Focalin and Focalin XR.

Considering the two chiral centers within its structure, Methylphenidate presents the possibility of four isomers. Among these, d-three-methylphenidate predominantly manifests the pharmacologically desired effects. Notably, the erythro diastereomers possess pressor amine properties, distinguishing them from the threo diastereomers. Initially, the drug was available as a 4:1 mixture of erythro:threo diastereomers, but it was subsequently reformulated to consist exclusively of the threo diastereomers. “TMP” denotes a three-product devoid of any erythro diastereomers, specifically (±)-three-methylphenidate. Since the three isomers are energetically favored, removing undesired erythro isomers is straightforward.

The variant containing solely dextrorotatory Methylphenidate is occasionally referred to as d-TMP, although this terminology is infrequent. It is more commonly recognized as dexmethylphenidate, d-MPH, or d-three-methylphenidate. A comprehensive synthesis review of enantiomerically pure (2R,2’R)-(+)-three-methylphenidate hydrochloride has been published.

Pharmacology

Methylphenidate primarily functions as a norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor (NDRI), with its primary impact centered on dopamine modulation and, to a lesser degree, norepinephrine regulation. This action occurs by binding to and obstructing dopamine and norepinephrine transporters.

It is essential to recognize that while amphetamine and Methylphenidate have dopaminergic properties, their mechanisms of action differ somewhat. Specifically, Methylphenidate serves as a dopamine reuptake inhibitor, whereas amphetamine acts as both a releasing agent and a reuptake inhibitor for dopamine and norepinephrine. It is worth noting that the influence of these drugs on norepinephrine is relatively less potent than their effects on dopamine.

The precise mechanism by which Methylphenidate affects dopamine-norepinephrine release remains controversial. However, it deviates fundamentally from the majority of other phenethylamine derivatives. Methylphenidate is believed to augment the general firing rate, while amphetamine diminishes the firing rate and alters the monoamine flow via TAAR1 activation, representing a distinctive contrast in their modes of action.

Subjective effects

Disclaimer: The following effects are derived from the Subjective Effect Index (SEI), a research literature based on anecdotal user accounts and personal analyses conducted by contributors to PsychonautWiki. Therefore, they should be approached with a degree of caution.

Understanding that these effects may not manifest predictably or consistently, with higher doses more likely to encompass the complete spectrum of products, is essential. Adverse effects become more probable at elevated amounts and can contain addiction, severe harm, or even fatality ☠.

Physical:

- Stimulation: Methylphenidate typically imparts an energetic and stimulating sensation, though milder compared to amphetamine or methamphetamine and more robust than that of modafinil and caffeine. Lower to moderate doses promote general productivity, while higher doses may encourage physical activities like dancing, socializing, running, or cleaning. This stimulation can be characterized as “forced,” leading to difficulty remaining still, jaw clenching, involuntary bodily shakes, vibrations, extreme body shaking, unsteady hands, and reduced motor control.

- Increased heart rate

- Irregular heartbeat

- Dehydration

- Frequent urination

- Dry mouth

- Appetite suppression

- Increased perspiration

- Nausea (more likely at higher doses, tends to diminish quickly)

- Dizziness (more likely at higher doses, tends to diminish quickly)

- Teeth grinding (more common at higher doses but less pronounced than with other stimulants like amphetamine or MDMA)

- Vasoconstriction

- Increased libido (not as intense or reliable as amphetamines or cocaine, especially at higher doses)

- Pupil dilation

Cognitive:

- Anxiety (slightly more frequent than with other common stimulants like amphetamine or cocaine)

- Cognitive euphoria (milder than other stimulants, may occur at higher or non-oral doses)

- Ego inflation

- Emotion suppression (most intense at light and typical doses, often associated with medical usage rather than recreational)

- Derealization (common at moderate/high doses)

- Focus enhancement (most effective at low to moderate doses; higher doses can impair concentration)

- Wakefulness

- Memory enhancement (therapeutic doses improve working memory in both standard and ADHD individuals)

- Time distortion (perception of time speeding up)

- Thought acceleration

- Thought organization

- Analysis enhancement

- Motivation enhancement

- Suggestibility suppression

- Increased music appreciation (milder compared to amphetamine or cocaine, more prominent at higher doses)

- Compulsive redosing (reported but less frequent than with other common stimulants, usually at high or non-oral doses)

After:

The after-effects during the decline of a stimulant experience are generally negative and uncomfortable compared to the peak effects. This is often called a “comedown” and results from neurotransmitter depletion. Common after-effects include:

- Anxiety

- Cognitive fatigue

- Depression

- Irritability

- Motivation suppression

- Increased heart rate

- Thought deceleration

- Wakefulness

Compared to other stimulants like amphetamine and caffeine, methylphenidate exhibits more pronounced after-effects akin to MDMA.

Toxicity

A toxic dose of Methylphenidate is considered to be more than 2 mg/kg or 60 mg of an immediate-release formulation or more than 4 mg/kg or 120 mg of an intact extended-release formulation. In most cases in one study, methylphenidate overdose was asymptomatic or characterized by minor symptoms, even in children under age 6.

However, a significant amount of patients (31%) in the study developed symptoms typical of stimulant overdose, most commonly tachycardia, agitation, and paradoxically lethargy. In the 2012 National Poison Data System report, methylphenidate exposure was reported 9,787 times, with 1,609 reporting no adverse effects, 1,009 reporting mild effects, 662 reporting moderate effects, 33 reporting significant symptoms, and no cases resulting in death.

It is strongly advised to use harm reduction practices if using this substance.

Dependence and abuse potential

In terms of its tolerance, Methylphenidate can be used multiple days in a row for extended periods and is often prescribed to be used in this way. Tolerance to many of the effects of Methylphenidate develops with prolonged and repeated use. Users have to administer increasingly large doses to achieve the same impact.

In the case of acute (i.e., one-off) exposure, it generally takes about 3 – 7 days for the tolerance to be reduced to half and 1 – 2 weeks to be back at baseline (in the absence of further consumption). Methylphenidate presents cross-tolerance with all dopaminergic stimulants, meaning that after consuming Methylphenidate, all stimulants will have a reduced effect.”

As with other stimulants, the chronic use of Methylphenidate can be considered moderately addictive with a high potential for abuse and is capable of causing psychological dependence among certain users. When addiction has developed, cravings and withdrawal effects may occur if a person suddenly stops their usage.

Methylphenidate has some potential for abuse due to its action on dopamine transporters. Methylphenidate, like other stimulants, increases dopamine levels in the brain. However, at therapeutic doses, this increase is slow, and thus, euphoria only rarely occurs, even when it is administered intravenously. The abuse and addiction potential of Methylphenidate is, therefore, significantly lower than other dopaminergic stimulants.

The abuse potential is increased when Methylphenidate is crushed and insufflated (snorted) or injected. It should be noted that due to the fillers in the pill, however, this can harm the nasal cavities, and intravenous use can cause emphysema (a lower respiratory tract disease, aka Ritalin lung, when caused by Ritalin tablets). The intravenous use of Methylphenidate, commonly marketed as Ritalin and widely used as a stimulant in treating attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, can lead to emphysematous changes known as Ritalin lung.

. The primary source of Methylphenidate for abuse is the diversion from legitimate prescriptions rather than illicit synthesis. Those who use Methylphenidate medicinally generally take it orally as instructed, while intranasal and intravenous are the preferred means for recreational use. [26]

Psychosis

Main article: Stimulant psychosis

Chronic use (i.e., high dose, repeat dosing) may increase the risk of psychosis. The safety profile of short-term methylphenidate therapy has been well-established, with short-term clinical trials revealing a very low incidence (0.1%) of methylphenidate-induced psychosis at therapeutic dose levels.

Psychotic symptoms from Methylphenidate can include hearing voices, visual hallucinations, urges to harm oneself, severe anxiety, mania, disinhibition, paranoid and grandiose delusions, confusion, emotional suppression, increased aggression, and irritability.

Combination with alcohol

Methylphenidate (when taken orally) has a low bioavailability, around 30%. Suppose taken with alcohol (ethanol), blood plasma levels of dexmethylphenidate increase by up to 40%. A metabolite called ethylphenidate is also formed.

Dangerous interactions

Warning: Many psychoactive substances that are reasonably safe to use alone can suddenly become dangerous and even life-threatening when combined with certain other substances. The following list provides some known dangerous interactions (although it is not guaranteed to include all of them).

Always conduct independent research (e.g., Google, DuckDuckGo, PubMed) to ensure that a combination of two or more substances is safe to consume. Some of the listed interactions have been sourced from TripSit.

- 25x-NBOMe & 25x-NBOH – 25x compounds are highly stimulating and physically straining. Combinations with Methylphenidate should be strictly avoided due to excessive stimulation and heart strain risk. In extreme cases, this can result in increased blood pressure, vasoconstriction, panic attacks, thought loops, seizures, and heart failure.

- Alcohol – Combining alcohol with stimulants can be dangerous due to the risk of accidental over-intoxication. Stimulants mask alcohol’s depressant effects, which most people use to assess their degree of intoxication. Once the motivation wears off, the depressant effects will be left unopposed, which can result in blackouts and severe respiratory depression. If mixing, users should strictly limit themselves to only drinking a certain amount of alcohol per hour.

- DXM – Combinations with DXM should be avoided due to its inhibiting effects on serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake. There is an increased risk of panic attacks, hypertensive crisis, or serotonin syndrome with serotonin releasers (MDMA, methylone, mephedrone, etc.). Monitor blood pressure carefully and avoid strenuous physical activity.

- MDMA – Any neurotoxic effects of MDMA are likely to be increased when other stimulants are present. Excess blood pressure and heart strain (cardiotoxicity) are also risks.

- MXE – Some reports suggest that combinations with MXE may dangerously increase blood pressure and the risk of mania and psychosis.

- Dissociatives – Both classes risk delusions, mania, and psychosis, and these risks may be multiplied when combined.

- Stimulants – Methylphenidate may be dangerous to combine with other stimulants like cocaine as they can increase one’s heart rate and blood pressure to dangerous levels.

- Tramadol – Tramadol is known to lower the seizure threshold[31], and combinations with stimulants may further increase this risk.

- MDMA – The neurotoxic effects of MDMA may be increased when combined with other stimulants.

- MAOIs – This combination may increase the amount of neurotransmitters such as dopamine to dangerous or even fatal levels. Examples include Syrian rue, banisteriopsis caapi, and some antidepressants.

Legal status

Internationally, methylphenidate is subject to various legal classifications:

Australia: Methylphenidate is categorized as a ‘Schedule 8’ controlled substance. These substances must be securely stored and can only be dispensed with a prescription. Possession without a prescription carries substantial fines and possible imprisonment.

Austria: Methylphenidate is permitted for medical use under the AMG (Arzneimittelgesetz Österreich) but is illegal when sold or possessed without a prescription, as per the SMG (Suchtmittelgesetz Österreich).

Canada: Methylphenidate is listed in Schedule III of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, placing it in the same category as LSD, psychedelic mushrooms, and mescaline. Possessing without a prescription under Part G (section G.01.002) of the Food and Drug Regulations as outlined in the Food and Drugs Act is unlawful.

Germany: Methylphenidate is classified as a controlled substance under Anlage III of the BtMG. It can only be prescribed on a narcotic prescription form.

New Zealand: Methylphenidate is classified as a ‘Class B2 controlled substance.’ Unauthorized possession can result in a six-month prison sentence, while distribution is punishable by a 14-year sentence.

Sweden: Methylphenidate is designated a List II controlled substance with recognized medical utility. Possession without a prescription may lead to up to three years of imprisonment.

Switzerland: Methylphenidate is explicitly named as a controlled substance under Verzeichnis A. Medicinal use is permitted.

Turkey: Methylphenidate is available only with a ‘red prescription’ and is illegal to sell or possess without a prescription.

United Kingdom: Methylphenidate is categorized as a controlled ‘Class B’ substance. Possession without a prescription can result in a sentence of up to 5 years and an unlimited fine, while supplying it may lead to 14 years and an unlimited fine.

United States: Methylphenidate is classified as a Schedule II controlled substance, applied to substances with recognized medical value but a high potential for abuse.

It’s important to note that the belief that methylphenidate can yield false-positive results for amphetamines in drug screenings is a widespread misconception. Extensive laboratory studies have found no immunoassay cross-reactivity, debunking this myth.

FAQ

1. What is Methylphenidate?

Methylphenidate is commonly prescribed to treat attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and narcolepsy. It belongs to the class of drugs known as central nervous system (CNS) stimulants.

2. How does Methylphenidate work?

Methylphenidate primarily works by increasing the levels of certain neurotransmitters, specifically dopamine and norepinephrine, in the brain. This helps improve focus, attention, and impulse control in individuals with ADHD.

3. What are the common brand names for Methylphenidate?

Methylphenidate is available under various brand names, including Ritalin, Concerta, Metadate, Daytrana, and Quillivant XR.

4. What are the common uses for Methylphenidate?

Methylphenidate is primarily prescribed for ADHD and narcolepsy. It helps manage the symptoms of these conditions, such as inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity.

5. Is Methylphenidate safe to use?

Methylphenidate is generally considered safe when used as prescribed by a healthcare professional. However, like all medications, it can have side effects, and a healthcare provider should closely monitor its use.

6. What are the potential side effects of Methylphenidate?

Common side effects of Methylphenidate may include insomnia, loss of appetite, nervousness, stomach upset, and increased heart rate. It’s essential to discuss any side effects with your healthcare provider.

7. Can Methylphenidate be abused or addictive?

Yes, Methylphenidate has a potential for abuse and addiction, mainly when not used as prescribed. It is classified as a Schedule II controlled substance in the United States due to its abuse potential.

8. How should Methylphenidate be taken?

Methylphenidate is typically taken orally in the form of tablets or capsules. Follow your healthcare provider’s instructions carefully regarding dosing and timing. Only crush or break extended-release records with approval from your doctor.

9. Can Methylphenidate be used by children and adults?

Yes, Methylphenidate is approved for use in children and adults, depending on the diagnosis and the healthcare provider’s recommendations.

10. Are there any drug interactions with Methylphenidate?

Methylphenidate can interact with certain medications, including monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), and should not be taken with them. Always inform your healthcare provider of all your drugs and supplements to avoid potential interactions.

11. Can Methylphenidate be stopped suddenly?

It is generally not recommended to stop Methylphenidate abruptly, especially if you have been taking it for an extended period. Consult your healthcare provider to discuss the best way to discontinue the medication.

12. Is it safe to drive or operate machinery while taking Methylphenidate?

Methylphenidate can affect your alertness and coordination, so assessing how it affects you personally before driving or operating heavy machinery is crucial. Your healthcare provider can offer guidance based on your specific situation.

13. Can Methylphenidate be used for purposes other than ADHD or narcolepsy?

Using Methylphenidate for non-medical or recreational purposes is illegal and unsafe. It can lead to serious health consequences and legal issues.

14. Is Methylphenidate available over-the-counter (OTC)?

No, Methylphenidate is not available without a prescription from a licensed healthcare provider. It is a controlled substance due to its potential for abuse.

References

- Health Canada – Ritalin (PDF)

- Lange, K. W., Reichl, S., Lange, K. M., Tucha, L., Tucha, O. (December 2010). “The history of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder”. ADHD Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders. 2 (4): 241–255. doi:10.1007/s12402-010-0045-8. ISSN 1866-6116.

- Diller, L. H. (1999). Running on ritalin: a physician reflects on children, society, and performance in a pill. Bantam Books. ISBN 9780553379068.

- Lange, K. W., Reichl, S., Lange, K. M., Tucha, L., Tucha, O. (2010). “The history of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder”. Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders. 2 (4): 241–255. doi:10.1007/s12402-010-0045-8. ISSN 1866-6116.

- “Narcotics monitoring board reports 66% increase in global consumption of methylphenidate”. The Pharmaceutical Journal. 2015. doi:10.1211/PJ.2015.20068042. ISSN 2053-6186.

- “The Top 300 of 2019”. ClinCalc. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- “Methylphenidate – Drug Usage Statistics”. ClinCalc. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- Heal, D. J., Pierce, D. M. (2006). “Methylphenidate and its Isomers: Their Role in the Treatment of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Using a Transdermal Delivery System”. CNS Drugs. 20 (9): 713–738. doi:10.2165/00023210-200620090-00002. ISSN 1172-7047.

- Prashad, M. (July 2001). “Approaches to the Preparation of Enantiomerically Pure (2R,2′R)-(+)-threo-Methylphenidate Hydrochloride”. Advanced Synthesis & Catalysis. 343 (5): 379–392. doi:10.1002/1615-4169(200107)343:5<379::AID-ADSC379>3.0.CO;2-4. ISSN 1615-4150.

- Heal, D. J., Pierce, D. M. (1 September 2006). “Methylphenidate and its Isomers”. CNS Drugs. 20 (9): 713–738. doi:10.2165/00023210-200620090-00002. ISSN 1179-1934.

- Iversen, L. (January 2006). “Neurotransmitter transporters and their impact on the development of psychopharmacology”. British Journal of Pharmacology. 147 (Suppl 1): S82–S88. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706428. ISSN 0007-1188.

- Volkow, N. D., Wang, G. J., Fowler, J. S., Gatley, S. J., Logan, J., Ding, Y. S., Hitzemann, R., Pappas, N. (October 1998). “Dopamine transporter occupancies in the human brain induced by therapeutic doses of oral methylphenidate”. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 155 (10): 1325–1331. doi:10.1176/ajp.155.10.1325. ISSN 0002-953X.

- Focalin XR review

- Concerta XL slow release

- Montastruc, F., Montastruc, G., Montastruc, J.-L., Revet, A. (22 June 2016). “Cardiovascular safety of methylphenidate should also be considered in adults”. BMJ: i3418. doi:10.1136/bmj.i3418. ISSN 1756-1833.

- Leonard, B. E., McCartan, D., White, J., King, D. J. (April 2004). “Methylphenidate: a review of its neuropharmacological, neuropsychological and adverse clinical effects”. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental. 19 (3): 151–180. doi:10.1002/hup.579. ISSN 0885-6222.

- Nestler, E. J., Hyman, S. E., Malenka, R. C. (2009). Molecular neuropharmacology: a foundation for clinical neuroscience (2nd ed ed.). McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 9780071481274.

- Nutt, D., King, L. A., Saulsbury, W., Blakemore, C. (24 March 2007). “Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse”. The Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–1053. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. ISSN 0140-6736.

- Scharman, E. J., Erdman, A. R., Cobaugh, D. J., Olson, K. R., Woolf, A. D., Caravati, E. M., Chyka, P. A., Booze, L. LL., Manoguerra, A. S., Nelson, L. S., Christianson, G., Troutman, W. G., American Association of Poison Control Centers (November 2007). “Methylphenidate poisoning: an evidence-based consensus guideline for out-of-hospital management”. Clinical Toxicology (Philadelphia, Pa.). 45 (7): 737–752. doi:10.1080/15563650701665175. ISSN 1556-3650.

- White, S. R., Yadao, C. M. (1 December 2000). “Characterization of Methylphenidate Exposures Reported to a Regional Poison Control Center”. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 154 (12): 1199. doi:10.1001/archpedi.154.12.1199. ISSN 1072-4710.

- 2012 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers ’ National Poison Data System (NPDS)

- Swanson, J., Gupta, S., Guinta, D., Flynn, D., Agler, D., Lerner, M., Williams, L., Shoulson, I., Wigal, S. (September 1999). “Acute tolerance to methylphenidate in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children”. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 66 (3): 295–305. doi:10.1016/S0009-9236(99)70038-X. ISSN 0009-9236.

- Volkow, N. D., Wang, G. J., Fowler, J. S., Gatley, S. J., Logan, J., Ding, Y. S., Dewey, S. L., Hitzemann, R., Gifford, A. N., Pappas, N. R. (January 1999). “Blockade of striatal dopamine transporters by intravenous methylphenidate is not sufficient to induce self-reports of “high””. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 288 (1): 14–20. ISSN 0022-3565.

- Volkow, N. D., Swanson, J. M. (November 2003). “Variables That Affect the Clinical Use and Abuse of Methylphenidate in the Treatment of ADHD”. American Journal of Psychiatry. 160 (11): 1909–1918. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.11.1909. ISSN 0002-953X.

- Morton, W. A., Stockton, G. G. (October 2000). “Methylphenidate Abuse and Psychiatric Side Effects”. Primary Care Companion to The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2 (5): 159–164. ISSN 1523-5998.

- Klein-Schwartz, W. (April 2002). “Abuse and toxicity of methylphenidate:”. Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 14 (2): 219–223. doi:10.1097/00008480-200204000-00013. ISSN 1040-8703.

- Spensley, J., Rockwell, D. A. (20 April 1972). “Psychosis during Methylphenidate Abuse”. New England Journal of Medicine. 286 (16): 880–881. doi:10.1056/NEJM197204202861607. ISSN 0028-4793.

- Ritalin & Ritalin-SR Prescribing Information

- Patrick, K., Straughn, A., Minhinnett, R., Yeatts, S., Herrin, A., DeVane, C., Malcolm, R., Janis, G., Markowitz, J. (March 2007). “Influence of Ethanol and Gender on Methylphenidate Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics”. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 81 (3): 346–353. doi:10.1038/sj.clpt.6100082. ISSN 0009-9236.

- Markowitz, J. S., DeVane, C. L., Boulton, D. W., Nahas, Z., Risch, S. C., Diamond, F., Patrick, K. S. (June 2000). “Ethylphenidate formation in human subjects after the administration of a single dose of methylphenidate and ethanol”. Drug Metabolism and Disposition: The Biological Fate of Chemicals. 28 (6): 620–624. ISSN 0090-9556.

- Talaie, H.; Panahandeh, R.; Fayaznouri, M. R.; Asadi, Z.; Abdollahi, M. (2009). “Dose-independent occurrence of seizure with tramadol”. Journal of Medical Toxicology. 5 (2): 63–67. doi:10.1007/BF03161089. eISSN 1937-6995. ISSN 1556-9039. OCLC 163567183.

- Gillman, P. K. (2005). “Monoamine oxidase inhibitors, opioid analgesics and serotonin toxicity”. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 95 (4): 434–441. doi:10.1093/bja/aei210 Freely accessible. eISSN 1471-6771. ISSN 0007-0912. OCLC 01537271. PMID 16051647.

- “Green List: Annex to the annual statistical report on psychotropic substances (form P)” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 August 2012. (1.63 MB) 23rd edition. August 2003. International Narcotics Board, Vienna International Centre. Retrieved 2 March 2006.

- “POISONS STANDARD DECEMBER 2019”. Office of Parliamentary Counsel. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- “SCHEDULE III”. Department of Justice. Archived from the original on April 16, 2011. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- Anlage III BtMG – Einzelnorm

- Narkotikastrafflag (1968:64) (NSL)

- “Verordnung des EDI über die Verzeichnisse der Betäubungsmittel, psychotropen Stoffe, Vorläuferstoffe und Hilfschemikalien” (in German). Bundeskanzlei [Federal Chancellery of Switzerland]. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- KIRMIZI REÇETEYE TABİ İLAÇLAR

- Misuse of Drugs Act 1971

- Breindahl, Torben; Hindersson, Peter (2012). “Methylphenidate is Distinguished from Amphetamine in Drug-of-Abuse Testing”. Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 36 (7): 538–539. doi:10.1093/jat/bks056. ISSN 0146-4760.

Leave a Reply