- 1 Exploring the Dynamics of Cocaine Market Trends

- 2 Understanding the Attraction to Cocaine Powder

- 3 The Emergence of Unique Variants Like Pink Cocaine Drug

- 4 Buying Cocaine Online and Its Risks

- 5 Alternatives to the Traditional Market

- 6 Concluding Thoughts on Cocaine’s Shifting Dynamics

- 7 Summary

- 8 History and culture

- 9 Chemistry

- 10 Pharmacology

- 11 Subjective effects

- 12 Forms

- 13 Toxicity

- 14 Legal status

- 15 FAQ

- 15.1 1. What is cocaine?

- 15.2 2. How is cocaine typically used?

- 15.3 3. What are the short-term effects of cocaine use?

- 15.4 4. What are the risks and dangers associated with cocaine use?

- 15.5 5. Is cocaine addictive?

- 15.6 6. Are there any medical uses for cocaine?

- 15.7 7. How long do the effects of cocaine last?

- 15.8 8. Can cocaine use lead to long-term health problems?

- 15.9 9. Is there any safe or responsible way to use cocaine?

- 15.10 10. What should I do if I or someone I know is struggling with cocaine addiction?

- 15.11 11. Is cocaine use illegal?

- 15.12 12. Can cocaine use be detected in drug tests?

- 15.13 13. What resources are available for individuals seeking help for cocaine addiction?

- 16 References

Exploring the Dynamics of Cocaine Market Trends

Cocaine has held an infamous reputation for decades, captivating attention both for its widespread use and the societal challenges it presents. Whether addressed as a cultural phenomenon or tackled in the context of its legal and illegal trade, the subject of cocaine and its market dynamics sparks curiosity and concern. Today, we’ll evaluate some key facets linked to this pervasive drug, using relevant search terms to build a deeper understanding of the broader discussion surrounding it.

Understanding the Attraction to Cocaine Powder

Cocaine powder stands out as one of the most commonly recognized forms of the drug. Its fine, white crystalline texture has been widely associated with its recreational use. Many individuals seek to buy cocaine online, a controversial trend that speaks to the growing digital marketplace for substances. This, in turn, poses a significant challenge for regulatory bodies attempting to control the distribution of such drugs.

For users, the allure often lies in the promised effects. These “cocaines drug effects” might include feelings of euphoria, increased energy, and temporary confidence boosts. However, the initial draw fades quickly, leaving serious ramifications in its wake, including heightened addiction risks and adverse health outcomes.

The Emergence of Unique Variants Like Pink Cocaine Drug

The rise of variants like the pink cocaine drug adds a new layer to the conversation. Often marketed as exotic and exclusive, pink cocaine appeals to niche audiences seeking to explore diverse recreational experiences. Skepticism surrounds what drug is pink powder, as it is often composed of a mix of substances that make potency and safety questionable. Variants like this point to rapid shifts in the marketplace and pose challenges for law enforcement and public health educators alike.

Trending searches, such as where can I buy cocaine, further underline this growing niche. Users seek specific sources, relying on the anonymity of online platforms to make transactions. But amid this, the risks of consuming unknown mixtures, such as liquid cocaine drug versions, add a layer of unpredictability to this growing demand.

Buying Cocaine Online and Its Risks

The question of where to buy cocaine has increasingly led individuals to turn to online platforms. While the internet provides unprecedented access, it also brings considerable risks. Those attempting buying cocaine online often encounter counterfeit products, scams, and even legal repercussions. Despite promises regarding quality, buying medications or substances online often involves taking a leap of faith that can end in dangerous consequences.

For sellers, how to sell cocaine and maintaining an online presence is a high-stakes gamble. Law enforcement cracks down heavily on digital operations, and cocaines drug bust operations regularly make headlines across the globe. These busts, while impactful in disrupting supply chains, often fail to address the consumer demand fueling these operations.

Alternatives to the Traditional Market

Interestingly, the concept of selling cocaine has expanded beyond the streets. Powder cocaine, often referred to in slang as coke powder, remains a major player, but new forms like sniffing powder and liquid cocaine are surfacing. These emerging formats capitalize on consumer curiosity—leveraging unique branding terms to draw attention while presenting evolving challenges to authorities.

The availability of substances like cocain for sale or cocaine for sale on digital black markets reflects a significant evolution in narcotics trafficking. Carefully crafted marketing verbiage often entices buyers who are unaware of the full legal and physical ramifications involved.

Concluding Thoughts on Cocaine’s Shifting Dynamics

From powder cocaine to experimental variants like pink cocaine drug, the industry around cocaine is both far-reaching and rapidly changing. Whether driven by the desire to purchase from secure sources, inquiries on how to buy cocaine, or attempts to harness anonymity with keywords like where can I buy cocaine, the conversation around cocaine is escalating to a global scale.

Ultimately, any exploration of buying cocaine drugs or engaging within its market, physically or digitally, underscores the need for awareness. Regulatory efforts, public education, and healthcare support are critical to managing and mitigating the damaging effects of this infamous drug. Each day offers an opportunity to not only understand the nature of the cocaine market but also its impact on individuals and societies everywhere.

Summary

Cocaine, also known colloquially as coke, cola, snow, blow, white, and other names, belongs to the tropane class of classical stimulant substances. This alkaloid is naturally derived from the leaves of coca plants, primarily Erythroxylum coca and Erythroxylum novogranatense. Cocaine’s mechanism of action involves elevating serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine levels in the brain.

This illicit substance is among the world’s most widely distributed and heavily regulated drugs. A 2007 United Nations report ranked it the second most frequently used substance globally, trailing only behind cannabis. Cocaine is categorized as a significant street drug and a substance of abuse, alongside heroin and methamphetamine.

Its subjective effects encompass stimulation, heightened blood pressure, appetite suppression, disinhibition, increased motivation, ego inflation, boosted libido, and euphoria. Cocaine is typically administered through insufflation (commonly known as “snorting” or “sniffing”) and occasionally via injection. While oral consumption is less common, it yields a considerably longer duration of effects—around 60 minutes, as opposed to the 10 to 20 minutes experienced with insufflation or 5 minutes when smoked.

The typical cocaine high is characterized by a swift onset and brief duration, featuring an intense euphoric “rush” followed by a noticeable comedown or “crash,” which can encourage compulsive redosing. Prolonged and excessive use can elevate the risk of anxiety, paranoia, minor hallucinations, mania, and, in rare instances, psychosis.

Cocaine carries a high potential for abuse. Chronic use, particularly at high doses and with repeated administration, is associated with the development of tolerance and physiological dependence, which can become severe if untreated.

Moreover, there is evidence suggesting that cocaine presents distinct cardiotoxic hazards when compared to other central nervous system stimulants, including the entire amphetamine class. Even occasional use has been linked to the emergence of enduring heart conditions and appears to trigger sudden cardiac death in susceptible individuals (see the relevant section for further details).

It is strongly recommended to practice harm reduction measures to minimize associated risks and potential harm when using this substance.

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name | |

| CAS Number | 50-36-2 |

|---|---|

| PubChem CID | 446220 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 2286 |

| DrugBank | DB00907 |

| ChemSpider | 10194104 |

| UNII | I5Y540LHVR |

| KEGG | D00110 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:27958 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL370805 |

| PDB ligand | COC (PDBe, RCSB PDB) |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID2038443 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.030 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C17H21NO4 |

| Molar mass | 303.358 g·mol−1 |

History and culture

Cocaine, known informally as coke, cola, snow, blow, white, and by various other names, has a rich history dating back a thousand years. Evidence of its use has been discovered in a rock shelter in Bolivia, where paraphernalia containing traces of five psychoactive chemicals, including cocaine and components of ayahuasca, were found.

In its early days, cocaine was not consumed as the powder we recognize today but as coca leaves, which were chewed to produce a milder stimulant effect akin to caffeine. This transition marked the beginning of cocaine’s separation from coca leaf use. The isolation of cocaine alkaloid was first documented in 1855 by German chemist Friedrich Gaedcke in the journal “Archiv der Pharmazie,” where he named it “erythoxyline.” In 1860, Albert Niemann isolated the alkaloid from coca and bestowed upon it the name cocaine. This marked the inception of cocaine’s journey away from coca leaf usage, and it soon piqued the interest of the Western medical community, leading to research publications within pharmaceutical circles.

One notable publication was Sigmund Freud’s “Cocaine Papers,” which, upon their initial release and rediscovery in 1974, significantly contributed to cocaine’s popularity. Freud speculated on cocaine’s medical potential as an anaesthetic due to its numbing effects and impact on hunger, sleep, and fatigue. He noted feelings of exhilaration, euphoria, increased self-control, and enhanced vitality, all without the unpleasant after-effects of alcohol. This contrasts with the modern understanding of cocaine’s propensity to induce cravings and compulsive redosing.

Freud also suggested cocaine’s use in morphine withdrawal treatment. His work culminated in “Uber Coca” in 1884, offering a scientific breakdown of cocaine’s potential uses and detailing various effects, including the euphoria and trademark mouth numbing.

According to a 2007 United Nations report, cocaine is the world’s second most widely used illicit substance, trailing only behind cannabis. In terms of usage rates as of 2007, Spain led with the highest rate (3.0% of adults in the previous year), followed by the United States (2.8%), England and Wales (2.4%), Canada (2.3%), Italy (2.1%), Bolivia (1.9%), Chile (1.8%), and Scotland (1.5%).

The name “cocaine” is derived from “coca” and the alkaloid suffix “-ine.” Cocaine boasts many common or street names, including coke, coca, cola, snow, ski, blow, nose candy, white, girl, and various regional variations such as Biff, Charlie, lemon, and flake in the UK.

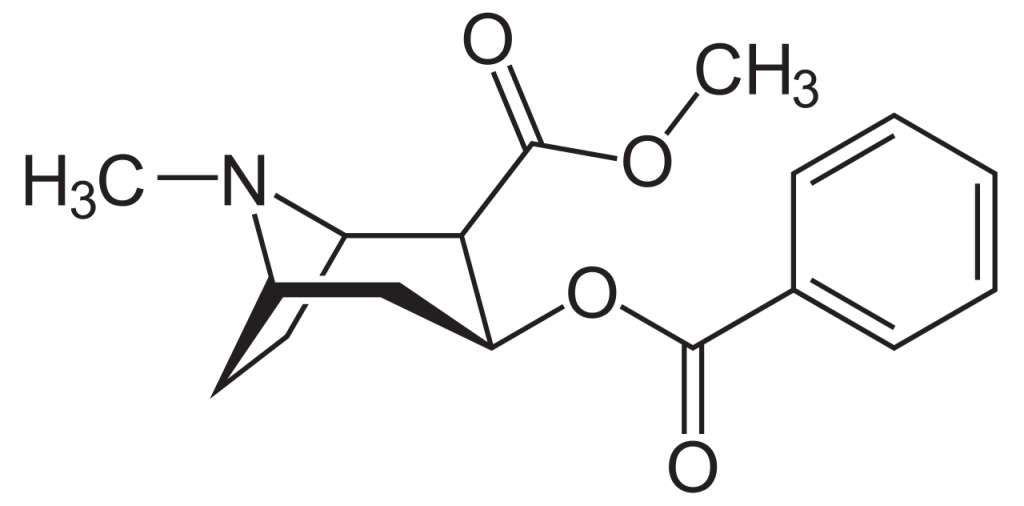

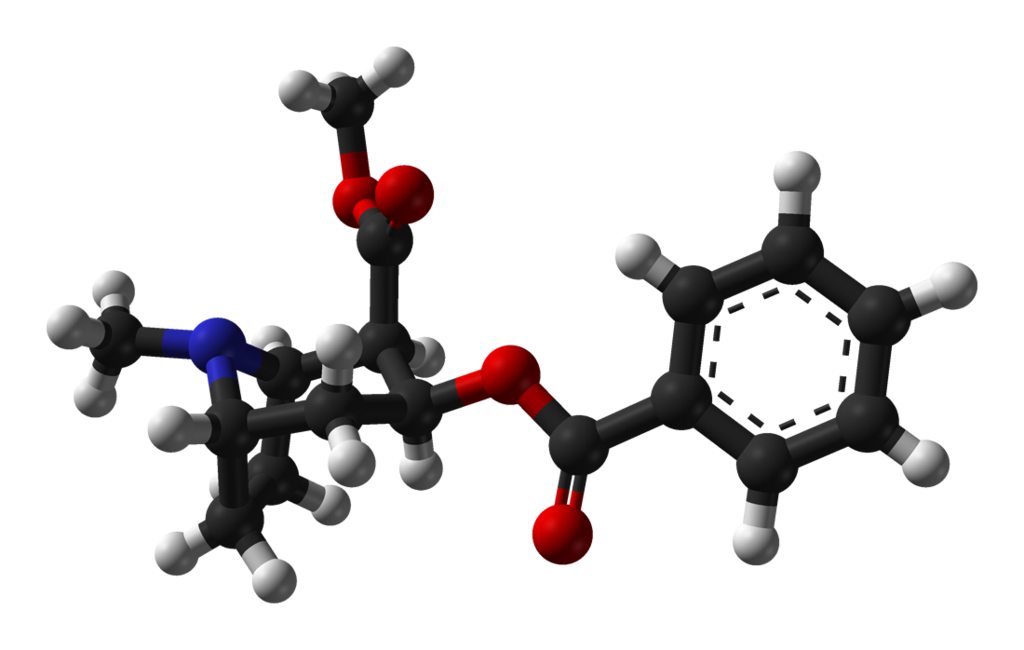

Chemistry

Cocaine, a tropane alkaloid, naturally occurs in the coca plant leaves, Erythroxylum coca. It is most commonly encountered in its hydrochloride salt form, typically synthesized in clandestine laboratories in countries like Colombia. Notably, cocaine is sensitive to high temperatures and tends to decompose when exposed to intense heat. To facilitate vaporization, cocaine is sometimes converted into alternative forms: the freebase and hydrogen carbonate salts. These variants, known as cocaine base and “crack,” respectively, possess significantly lower boiling points than hydrochloride salt.

Cocaine’s chemical composition comprises three key components: a hydrophilic methyl ester moiety and a lipophilic benzoyl ester moiety. These elements replace the carboxylic acid and hydroxyl groups of ecgonine, facilitating rapid absorption through nasal membranes and the blood-brain barrier.

Due to two ester groups, cocaine exhibits relative instability in warm and humid conditions. When stored openly or in environments with high moisture levels, cocaine may experience a decrease in apparent potency over time. This decline is attributed to hydrolysis, leading to methyl ecgonine or benzoylecgonine formation.

Pharmacology

Cocaine’s primary and extensively studied impact on the central nervous system revolves around its ability to block the dopamine transporter. In essence, it functions as a reuptake inhibitor, halting the recycling of dopamine. This interruption leads to an excessive accumulation of dopamine in the synaptic cleft, the junction between neurons. The consequence is a heightened and prolonged post-synaptic effect of dopaminergic signalling. Additionally, to a lesser degree, cocaine exhibits similar reuptake-inhibiting effects on serotonin and noradrenaline neurotransmitters. This sudden surge of neurotransmitters produces the characteristic euphoric effects associated with cocaine use.

The pharmacodynamics of cocaine entail intricate interactions among neurotransmitters, with approximate ratios of monoamine uptake inhibition in rats being serotonin: dopamine = 2:3 and serotonin: norepinephrine = 2:5. The central focus of cocaine’s impact lies in its blockade of the dopamine transporter protein. Ordinarily, dopamine released during neural signalling is reabsorbed through this transporter, which binds to the neurotransmitter and shuttles it back into the presynaptic neuron for storage.

Cocaine forms a tight bond with the dopamine transporter, creating a complex that impedes the transporter’s function. Consequently, the dopamine transporter can no longer perform its reuptake duty, leading to the accumulation of dopamine in the synaptic cleft. This heightened dopamine concentration activates post-synaptic dopamine receptors, rewarding the drug and driving compulsive cocaine use.

Subjective effects

Disclaimer: The effects described below are based on anecdotal user reports and the subjective analysis of PsychonautWiki contributors, known as the Subjective Effect Index (SEI). It is essential to approach these effects with a degree of scepticism.

Additionally, these effects may not manifest predictably or reliably, with higher doses more likely to produce the full effects. It is crucial to note that higher doses can also increase the risk of adverse effects, including addiction, severe injury, or even death ☠.

Cocaine’s cognitive effects are dose-dependent, increasing intensity as the dosage increases. The typical mental state induced by cocaine is characterized by profound mental stimulation, heightened motivation, increased libido, and an overwhelming sense of euphoria and satisfaction. However, it’s essential to consider that the subjective experience of cocaine can vary significantly due to differences in quality and purity.

Physical Effects:

- Stimulation: Cocaine provides an intense and energetic stimulation comparable to methamphetamine but often stronger than amphetamines, modafinil, caffeine, or methylphenidate. Users may experience uncontrollable physical movements at higher doses, including jaw clenching, body shakes, and vibrations, leading to a lack of fine motor control. This stimulation transitions into mild fatigue and exhaustion during the comedown.

- Abnormal Heartbeat: Cocaine significantly elevates heart rate to potentially dangerous levels, especially with prolonged or high-dose use. Even minimal physical activity, such as walking, can cause an unusually rapid heartbeat, surpassing the effects of other stimulants. Users are advised to engage in less physical activity than usual due to the drug’s pronounced impact on heart rate and cardiac output.

- Physical Euphoria

- Increased Heart Rate

- Increased Blood Pressure

- Appetite Suppression: This effect can be less intense for inexperienced users.

- Enhanced Bodily Control

- Bronchodilation: Sometimes, this effect can be very noticeable, potentially leading to difficulty swallowing.

- Dehydration

- Frequent Urination

- Bowel Movements

- Increased Body Temperature

- Increased Perspiration

- Pain Relief: Cocaine’s anaesthetic properties cause numbness, primarily felt in the nasal passages, throat, and front teeth when insufflated. A numbing effect on the entire face may indicate the presence of cutting agents such as Novacaine.

- Pupil Dilation

- Mouth Numbing

- Tactile Hallucinations: High doses or prolonged use of cocaine can lead to hallucinatory sensations, such as the feeling of bugs crawling on or under the skin (formication), often referred to as “coke bugs.”

- Teeth Grinding: This effect is generally less intense than with MDMA.

- Temporary Erectile Dysfunction

- Vasoconstriction: Cocaine, like other stimulants, can cause users to feel colder in certain body parts, particularly the hands. Combining cocaine with other vasoconstrictors, such as nicotine, can be dangerous.

Cognitive Effects:

- Analysis Enhancement: Typically present at low to moderate doses.

- Anxiety or Anxiety Suppression

- Compulsive Redosing: More prevalent with cocaine than with most other commonly used stimulants.

- Cognitive Euphoria: When insufflated, an initial “rush” is felt within the first 5-10 minutes, followed by a lesser degree of mental euphoria. However, other mental and physical effects may persist beyond this initial rush.

- Disinhibition

- Ego Inflation: Occurs inconsistently or sporadically, sometimes only on the tail-end or with repeated dosing. It is notably less pronounced than with MDMA and entactogens.

- Focus Enhancement: Most effective at low to moderate doses; higher doses may impair concentration. However, it is less prominent than with amphetamines.

- Increased Libido: This may be more prominent due to its effects on testosterone levels, in addition to increased dopamine. Dosage can impact the intensity of this effect.

- Increased Music Appreciation: May diminish or disappear with regular or prolonged use.

- Irritability: Often experienced during the peak or comedown phase, known colloquially as “coke rage.”

- Mania: Particularly noticeable with insufflation, marking cocaine as less clear-headed and functional compared to equipotent doses of amphetamines.

- Memory Enhancement: Typically present only during the brief peak effects but can be notably pronounced, likely due to cocaine’s increased signalling of acetylcholine in the brain.

- Memory Suppression: More prevalent at higher doses, primarily affecting short-term memory.

- Suggestibility Suppression

- Motivation Enhancement

- Ringing in Ears: Commonly experienced when cocaine is administered intravenously, referred to as a “bell ringer.”

- Thought Acceleration: This aspect may persist even after the main effects have worn off.

- Thought Organization: Less pronounced compared to amphetamines.

- Time Compression: Users may feel that time passes much quicker than usual.

- Wakefulness: Less prominent compared to amphetamine stimulants, primarily methamphetamine.

After Effects:

The effects of stimulant use during the comedown phase are often adverse and uncomfortable, resulting from neurotransmitter depletion. The severity of the “crash” may depend on the dose. Common aftereffects include anxiety, cognitive fatigue, compulsive redosing, depression (especially at higher doses), irritability, motivation suppression, respiratory depression, tactile hallucinations, thought deceleration, and headaches.

Forms

Cocaine Paste: An unrefined extract derived from coca leaves containing 40% to 91% cocaine sulfate, other coca alkaloids and varying amounts of benzoic acid, methanol, and kerosene.

Salts: Cocaine is classified as a weakly alkaline compound (an “alkaloid”) and can form different salts when combined with acidic substances. The hydrochloride (HCl) salt of cocaine is the most commonly encountered, although sulfate (-SO4) and nitrate (-NO3) salts are occasionally found. These salts have varying solubilities in different solvents. The hydrochloride salt is polar and highly soluble in water.

Freebase: “Freebase” refers to the primary form of cocaine, as opposed to the salt form. It is nearly insoluble in water, unlike the hydrochloride salt, making it unsuitable for sublingual use or insufflation. Freebase cocaine can be converted into the salt form by treatment with ethers, isopropyl alcohol, and hydrochloric acid.

“Crack”: “Crack” is a lower-purity form of freebase cocaine, typically produced by neutralizing cocaine hydrochloride with a solution of baking soda (sodium bicarbonate, NaHCO3) and water. This process results in a complex, brittle, off-white-to-brown substance that contains sodium carbonate, entrapped water, and other impurities.

Smoking or Vaporization: Inhaling cocaine by smoking or vaporizing it into the lungs leads to an almost immediate and highly potent “high,” known as a “rush.” While the stimulating effects can persist for hours, the euphoria is short-lived, often prompting users to seek more immediately.

Coca Leaf Infusions: In regions where coca leaves are grown, coca herbal infusions (coca tea) are consumed much like other medicinal herbal infusions worldwide. The legal sale of dried coca leaves, marketed as filtration bags for “coca tea,” is actively promoted by governments in Peru and Bolivia for its perceived medicinal properties. Native populations also use coca leaves for various purposes, including treating altitude sickness.

Coca Leaf Chewing: Chewing coca leaves, often with lime, is a common practice in coca-producing areas. This practice numbs the mouth and provides mild stimulation.

Toxicity

Long-term Cocaine Use and Neurotoxicity:

Chronic cocaine use has been demonstrated to lead to neurotoxic effects in rodents and humans, resulting in significant morbidity and mortality rates. Prolonged use or abuse of cocaine can also lead to the short-term downregulation of neurotransmitters.

Cardiovascular Risks

While neurological effects are a concern, cocaine’s most potentially harmful physical consequences are cardiovascular. High doses of cocaine pose a severe risk of cardiac adverse events, particularly sudden cardiac death, due to cocaine’s inhibition of cardiac sodium channels. Additionally, sustained cocaine use may result in cocaine-related cardiomyopathy.

Nasal and Nasopharyngeal Effects

Regular cocaine insufflation, the most common method of consumption, can cause detrimental effects on the nasal passages and cavities. These adverse effects encompass the loss of the sense of smell, nosebleeds, difficulty swallowing, hoarseness, and chronic rhinorrhea.

Harm Reduction

It is essential to emphasize harm reduction practices when using this substance.

Lethal Dosage

Vulnerable individuals have succumbed to doses as low as 30 mg applied to mucous membranes, while addicts may tolerate daily doses of up to 5 grams.

Dependence and Abuse Potential

Like other stimulants, chronic cocaine use carries a high potential for addiction and abuse, leading to psychological dependence in some users. Cravings and withdrawal symptoms can emerge upon discontinuation, with addiction being a significant risk for heavy recreational users but unlikely for typical medical use.

Tolerance and Cross-Tolerance

Tolerance to cocaine’s effects develops with prolonged and repeated use, necessitating larger doses for the same effects. Cocaine exhibits cross-tolerance with all dopaminergic stimulants, diminishing their effectiveness after cocaine consumption.

Withdrawal Symptoms

Regular cocaine use can lead to addiction. When discontinuing the substance abruptly, users may experience a “crash” accompanied by withdrawal symptoms, including paranoia, depression, decreased libido, anxiety, itching, mood swings, irritability, fatigue, insomnia, intense cravings, and, occasionally, nausea and vomiting. These symptoms can persist for weeks to months, with an enduring desire to continue using cocaine.

Psychosis

Cocaine carries the potential to induce temporary psychosis, with over half of cocaine users reporting psychotic symptoms at some point. Symptoms include paranoid delusions, hallucinations, and delusional parasitosis (the sensation of “cocaine bugs”). Cocaine-induced psychosis may intensify with repeated intermittent use.

Dangerous Interactions

Combining cocaine with certain substances can lead to dangerous and life-threatening interactions. Examples include:

- Increased anxiety levels when combined with psychedelics.

- Heightened risk of heart issues when mixed with alcohol.

- The potential for seizures when used with tramadol.

Always research potential interactions before consumption.

Legal status

Australia: Cocaine is categorized as a Schedule 8 controlled drug, allowing for limited medical use, but is otherwise prohibited.

Austria: Possessing, producing, and selling cocaine is illegal in Austria under the SMG (Suchtmittelgesetz Österreich).

Bolivia: Limited coca cultivation is lawful, with coca leaf chewing and tea consumption considered cultural practices. Processed cocaine remains illegal.

Brazil: Personal cocaine use is decriminalized, while public consumption is considered a crime. Cultivation, transportation, and sale are illegal.

Canada: Cocaine is classified as a Schedule I drug under Canada’s Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.

Colombia: Despite previous legalization of less than 1 gram of personal possession, sale and possession are now illegal under a new nationwide police code.

Germany: Cocaine is controlled under Anlage III BtMG (Narcotics Act, Schedule III) and can only be prescribed on a narcotic prescription form. Possession of up to 5 grams is considered minor and may lead to prosecution.

Hong Kong: Use and possession of cocaine is illegal, except with a license issued by the Department of Health.

India: Using and possessing cocaine is illegal and requires a 10-year sentence.

Lithuania: Cocaine is classified as a Schedule I substance, prohibiting possession, production, and trade.

Mexico: Small doses of cocaine for personal use, among other substances, were legalized as of August 25, 2009. No action is taken for those carrying up to half a gram.

The Netherlands: Cocaine is deemed an illegal hard drug under the Opium Law 1928. Possession, production, and trade are prohibited, although possession of less than half a gram is typically not punished.

New Zealand: Cocaine is categorized as a Class A drug, with specific preparations containing minimal cocaine base considered Class C.

Nigeria: Possession of cocaine is a crime.

Pakistan: Use and possession of cocaine are illegal.

Peru: Coca plant cultivation is legal, and coca leaves are openly sold. Possession of up to 2 grams of cocaine or up to 5 grams of cocaine basic paste is legal for personal use, subject to specific conditions.

Portugal: Personal cocaine use is decriminalized, with drug abuse addressed through administrative and medical interventions. Trafficking remains illegal.

Saudi Arabia: Use and possession of cocaine are punishable by death.

Singapore: Possessing over 30 grams of cocaine results in a mandatory death sentence, although the Department of Health can grant exceptions.

South Africa: Cocaine is a controlled substance.

Switzerland: Cocaine is a controlled substance listed under Verzeichnis A.

United Kingdom: Cocaine is classified as a Class A drug under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. Medical use by doctors for pain control is permitted.

United States: Cocaine is designated as a Schedule II Narcotic under the Controlled Substances Act of the United States.

FAQ

1. What is cocaine?

Cocaine is a powerful stimulant drug derived from the coca plant. It is known for stimulating and euphoric effects on the central nervous system.

2. How is cocaine typically used?

Cocaine is commonly used by snorting it in powder form or dissolving it and injecting it intravenously. It can also be smoked when converted into the “crack” form. Less commonly, it may be ingested orally.

3. What are the short-term effects of cocaine use?

Short-term effects of cocaine use include increased energy, alertness, and euphoria. Users may also experience increased heart rate, dilated pupils, decreased appetite, and heightened sensitivity to stimuli.

4. What are the risks and dangers associated with cocaine use?

Cocaine use can lead to various health risks, including addiction, cardiovascular problems, respiratory issues, anxiety, paranoia, and even overdose, which can be fatal. Long-term use can also result in physical and mental health problems.

5. Is cocaine addictive?

Yes, cocaine is highly addictive. Many individuals who use cocaine regularly develop a strong psychological and physical dependence on the drug, making quitting challenging.

6. Are there any medical uses for cocaine?

Cocaine does have limited medical uses, primarily as a local anaesthetic in specific medical procedures. However, its medical use is tightly regulated due to its potential for abuse.

7. How long do the effects of cocaine last?

The duration of cocaine’s effects can vary depending on the method of use. Snorting cocaine typically results in effects lasting 15 to 30 minutes, while smoking or injecting may lead to a shorter but more intense high.

8. Can cocaine use lead to long-term health problems?

Yes, chronic cocaine use can have severe consequences, including cardiovascular issues, respiratory problems, neurological impairments, mental health disorders like depression and anxiety, and damage to various organ systems.

9. Is there any safe or responsible way to use cocaine?

Cocaine use is associated with significant health risks, and there is no safe way to use it recreationally. It is a highly addictive drug with the potential for life-threatening consequences.

10. What should I do if I or someone I know is struggling with cocaine addiction?

If you or someone you know is facing cocaine addiction, seek help immediately. Contact a healthcare professional, addiction counsellor, or a local addiction treatment centre. Recovery is possible with the proper support and treatment.

11. Is cocaine use illegal?

In many countries, including the United States and most of Europe, the possession, sale, and use of cocaine for recreational purposes are illegal. Legal restrictions and penalties vary by location.

12. Can cocaine use be detected in drug tests?

Yes, cocaine use can typically be detected through various drug tests, including urine, blood, saliva, and hair. Detection times vary, but cocaine is generally detectable for several days to a few weeks after use.

13. What resources are available for individuals seeking help for cocaine addiction?

Numerous resources are available, including addiction treatment centres, support groups, counselling services, and hotlines. Organizations like Narcotics Anonymous (NA) and local addiction treatment facilities can assist.

Remember that cocaine use carries significant risks, and it is essential to prioritize your health and well-being. If you or someone you know is struggling with cocaine addiction, seeking help and support is crucial for recovery.

References

- Barnett, G., Hawks, R., Resnick, R. (March 1981). “Cocaine pharmacokinetics in humans”. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 3 (2–3): 353–366. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(81)90063-5. ISSN 0378-8741.

- Jeffcoat, A. R., Perez-Reyes, M., Hill, J. M., Sadler, B. M., Cook, C. E. (April 1989). “Cocaine disposition in humans after intravenous injection, nasal insufflation (snorting), or smoking”. Drug Metabolism and Disposition: The Biological Fate of Chemicals. 17 (2): 153–159. ISSN 0090-9556.

- Aggrawal, A. (1995). Narcotic Drugs. National Book Trust. ISBN 9788123713830.

- http://www.unodc.org/pdf/research/wdr07/WDR_2007.pdf

- Wilkinson, P., Van Dyke, C., Jatlow, P., Barash, P., Byck, R. (March 1980). “Intranasal and oral cocaine kinetics”. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 27 (3): 386–394. doi:10.1038/clpt.1980.52. ISSN 0009-9236.

- Coe, M. A., Jufer Phipps, R. A., Cone, E. J., Walsh, S. L. (1 June 2018). “Bioavailability and Pharmacokinetics of Oral Cocaine in Humans”. Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 42 (5): 285–292. doi:10.1093/jat/bky007. ISSN 0146-4760.

- Nutt, D., King, L. A., Saulsbury, W., Blakemore, C. (24 March 2007). “Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse”. The Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–1053. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. ISSN 0140-6736.

- O’Leary, M. E., Hancox, J. C. (28 January 2010). “Role of voltage-gated sodium, potassium and calcium channels in the development of cocaine-associated cardiac arrhythmias: Voltage-gated ion channels and cocaine-induced arrhythmia”. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 69 (5): 427–442. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03629.x. ISSN 0306-5251.

- Miller, M. J., Albarracin-Jordan, J., Moore, C., Capriles, J. M. (4 June 2019). “Chemical evidence for the use of multiple psychotropic plants in a 1,000-year-old ritual bundle from South America”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (23): 11207–11212. doi:10.1073/pnas.1902174116. ISSN 0027-8424.

- Gaedcke, F. (1855). Ueber das Erythroxylin, dargestellt aus den Blättern des in Südamerika cultivirten Strauches Erythroxylon Coca Lam. https://doi.org/10.1002/ardp.18551320208

- https://libgen.top/ads3b7a7a253eb54644e9ca79039ca3e0f105V1622B

- http://www.unodc.org/pdf/research/wdr07/WDR_2007.pdf

- Rothman, R. B., Baumann, M. H., Dersch, C. M., Romero, D. V., Rice, K. C., Carroll, F. I., Partilla, J. S. (1 January 2001). <32::AID-SYN5>3.0.CO;2-3 “Amphetamine-type central nervous system stimulants release norepinephrine more potently than they release dopamine and serotonin”. Synapse. 39 (1): 32–41. doi:10.1002/1098-2396(20010101)39:1<32::AID-SYN5>3.0.CO;2-3. ISSN 0887-4476.

- Hummel, M., Unterwald, E. M. (April 2002). “D1 dopamine receptor: A putative neurochemical and behavioral link to cocaine action”. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 191 (1): 17–27. doi:10.1002/jcp.10078. ISSN 0021-9541.

- Morani, A. S., Panwar, V., Grasing, K. (March 2013). “Tactile Hallucinations with Repetitive Movements Following Low-Dose Cocaine: Implications for Cocaine Reinforcement and Sensitization: Case Report”. The American Journal on Addictions. 22 (2): 181–182. doi:10.1111/j.1521-0391.2013.00336.x. ISSN 1055-0496.

- Urban Dictionary: Coke Rage

- https://one.nhtsa.gov/people/injury/research/job185drugs/cocain.htm

- Ask Erowid : ID 3151 : Can freebase cocaine be converted back to powder?

- Nutt, D., King, L. A., Saulsbury, W., Blakemore, C. (24 March 2007). “Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse”. The Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–1053. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. ISSN 0140-6736.

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7874143/

- “Cocaine-Related Cardiomyopathy: Overview, Cardiac Effects of Cocaine, Epidemiology”. 16 October 2021.

- Cocaine and crack drug profile

- Brady, K. T., Lydiard, R. B., Malcolm, R., Ballenger, J. C. (December 1991). “Cocaine-induced psychosis”. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 52 (12): 509–512. ISSN 0160-6689.

- Psychosis Among Substance Users

- Elliott, A., Mahmood, T., Smalligan, R. D. (March 2012). “Cocaine Bugs: A Case Report of Cocaine-Induced Delusions of Parasitosis: Cocaine Bugs”. The American Journal on Addictions. 21 (2): 180–181. doi:10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00208.x. ISSN 1055-0496.

- Schanzer, B. M., First, M. B., Dominguez, B., Hasin, D. S., Caton, C. L. M. (October 2006). “Diagnosing Psychotic Disorders in the Emergency Department in the Context of Substance Use”. Psychiatric Services. 57 (10): 1468–1473. doi:10.1176/ps.2006.57.10.1468. ISSN 1075-2730.

- Health, Poisons Standard October 2019

- “Suchtgiftverordnung”. Government of Austria. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2004-2006/2006/lei/l11343.htm

- http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-38.8/page-23.html#h-26

- http://www.signonsandiego.com/news/world/20040405-0915-legalizeddrugs.html

- http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2004/04/05/world/main610293.shtml

- “Gesetz über den Verkehr mit Betäubungsmitteln (Opiumgesetz)” (in German). Reichsministerium des Innern. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- “Anlage III BtMG” (in German). Bundesministerium der Justiz und für Verbraucherschutz. Retrieved December 19, 2019.

- “Bundesgerichtshof: Urt. v. 01.02.1985, Az.: 2 StR 685/84” (in German). 2. Strafsenat des Bundesgerichtshofs. February 1, 1985. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- http://vvkt.lt/lit/I-narkotiniu-ir-psichotropiniu-medziagu-saraas/312

- USATODAY.com – Mexico votes to legalize small amounts of cocaine, heroin and marijuana

- http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,193616,00.html

- http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2006/05/03/world/main1575608.shtml

- http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2006/04/12/world/main1491595.shtml

- http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/12535896

- http://www.lwl.org/LWL/Jugend/KoopSucht/nl/Repression/index_html#b

- http://www.drugsbeleid.nl/nederlands/projecten/drugsverbod_juridisch_ontmaskeren.htm

- http://www.druglawreform.info/en/country-information/peru/item/207-peru?pop=1&tmpl=component&print=1

- Tony (2012), Drugs in Peru: The Laws of Possession

- http://www.cato.org/pubs/wtpapers/greenwald_whitepaper.pdf

- “Verordnung des EDI über die Verzeichnisse der Betäubungsmittel, psychotropen Stoffe, Vorläuferstoffe und Hilfschemikalien” (in German). Bundeskanzlei [Federal Chancellery of Switzerland]. Retrieved January 1, 2020.