The online market for research chemicals, including the highly potent hallucinogen LSD, has been a cause for concern due to the proliferation of sellers offering these substances. This critical review highlights the key issues surrounding these LSD research chemical sellers.

First and foremost, the sale of LSD as a “research chemical” raises significant ethical and safety concerns. LSD is a powerful psychedelic compound with a long history of recreational use. Marketing it as a research chemical suggests that it is intended for scientific purposes, but in reality, many buyers are likely seeking it for recreational or self-experimentation purposes. This blurs the line between research and personal use and can lead to irresponsible consumption and potential harm.

Furthermore, the online availability of LSD research chemicals poses serious health risks. The purity and dosage of these substances are often questionable, as they are not regulated or subject to quality control measures like pharmaceutical drugs. Buyers risk receiving impure or mislabeled products, leading to unexpected and dangerous experiences.

Additionally, the lack of age restrictions and proper screening when purchasing LSD research chemicals online can make these substances accessible to individuals who should not have access to them. This includes minors and those with a history of mental health issues, putting them at greater risk for adverse reactions.

Moreover, the online market for LSD research chemicals has drawn the attention of authorities and regulatory bodies. Laws surrounding these substances constantly evolve, and sellers may face legal consequences.

Contents

- 1 Summary

- 2 Uses

- 3 Effects

- 4 Adverse effects

- 5 Overdose

- 6 Pharmacology

- 7 Chemistry

- 8 History

- 9 Legal status

- 10 Research

- 11 FAQ

- 11.1 1. What is LSD?

- 11.2 2. How is LSD typically consumed?

- 11.3 3. What are the effects of LSD?

- 11.4 4. Is LSD legal?

- 11.5 5. Can LSD be used for medical or therapeutic purposes?

- 11.6 6. What are the risks associated with LSD use?

- 11.7 7. Can LSD be addictive?

- 11.8 8. What precautions should be taken when using LSD?

- 11.9 9. Can LSD be detected in drug tests?

- 11.10 10. Is microdosing LSD safe?

- 11.11 11. How long does LSD stay in your system?

- 11.12 12. Can LSD cause permanent damage or psychosis?

- 12 References

Summary

LSD, scientifically known as Lysergic acid diethylamide and colloquially referred to as “acid,” is a potent psychedelic drug. Its effects typically involve heightened thoughts, emotions, and sensory perception. At higher doses, LSD primarily induces mental, visual, and auditory hallucinations. It often leads to dilated pupils, increased blood pressure, and elevated body temperature. The onset of effects generally occurs within half an hour and can last up to 20 hours, with an average trip duration of 8-12 hours. Additionally, LSD is known for its potential to trigger mystical experiences and ego dissolution. It is commonly used for both recreational purposes and spiritual exploration.

LSD is regarded as a prototypical psychedelic substance and holds significant scientific and cultural importance. It is synthesized solidly, usually as a powder or crystalline material. To make it consumable, solid LSD is dissolved in a liquid solvent, such as ethanol or distilled water, creating a solution that can be precisely dosed and applied to small pieces of blotter paper known as tabs. LSD is typically ingested orally or placed under the tongue.

From a pharmacological standpoint, LSD is considered non-addictive with a low potential for abuse. However, it can lead to adverse psychological reactions like anxiety, paranoia, and delusions. LSD is highly potent, with doses measured in micrograms, and can induce visual hallucinations even after a single use. Persistent visual disturbances and hallucinogen-persisting perception disorder (HPPD) can sometimes occur.

The mechanism of action of LSD primarily involves its agonistic activity at the 5-HT2A (serotonin) receptor. This leads to increased glutamatergic neurotransmission and reduced activity in the default mode network. Additionally, LSD binds to dopamine D1 and D2 receptors, contributing to its stimulating effects.

LSD’s discovery dates back to 1938 when Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann synthesized it from lysergic acid, a derivative of ergotamine in the ergot fungus. Hofmann accidentally ingested the substance in 1943, leading to the revelation of its effects on humans. During the 1950s and early 1960s, LSD garnered significant attention in psychiatry, with researchers investigating its potential therapeutic applications. The CIA also explored it in projects like MKUltra.

In the 1960s, LSD became symbolic of the counterculture movement for its perceived ability to expand consciousness. This association led to concerns about its impact on American values and its classification as a Schedule I controlled substance in 1968. The United Nations also designated it as Schedule 1 in 1971, and it currently lacks approved medical uses.

As of 2017, approximately 10% of individuals in the United States had used LSD at some point, with 0.7% reporting use in the last year. Notably, its popularity peaked during the 1960s to the 1980s, and its use among US adults increased by 56.4% from 2015 to 2018.

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name | |

| CAS Number | 50-37-3 |

|---|---|

| PubChem CID | 5761 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 17 |

| DrugBank | DB04829 |

| ChemSpider | 5558 |

| UNII | 8NA5SWF92O |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:6605 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL263881 |

| PDB ligand | 7LD (PDBe, RCSB PDB) |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID1023231 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.031 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C20H25N3O |

| Molar mass | 323.440 g·mol−1 |

Uses

Recreational Use: LSD is frequently employed as a substance for recreational purposes.

Spiritual Significance: LSD is recognized for its potential to induce profound spiritual experiences and is thus categorized as an entheogen. Some individuals have reported incidents of being detached from their physical bodies. 1966, Timothy Leary established the League for Spiritual Discovery, with LSD as its sacred sacrament. Stanislav Grof has noted that the religious and mystical encounters facilitated by LSD closely resemble descriptions found in the holy scriptures of major world religions and the ancient texts of various civilizations.

Medical Applications: For medical applications, LSD currently lacks approved uses. Nonetheless, a meta-analysis has indicated that a single dose of LSD can effectively reduce alcohol consumption among individuals grappling with alcoholism. LSD has also undergone research for potential therapeutic applications in addressing conditions such as depression, anxiety, and drug dependence, yielding promising initial results.

Effects

Potency:

LSD stands out for its remarkable power; even 20 micrograms (μg) can elicit noticeable effects.

Physical:

LSD can trigger various biological responses, including pupil dilation, decreased appetite, profuse sweating, and heightened wakefulness. Other physical reactions to LSD are highly diverse and non-specific, with some potentially arising as secondary responses to its psychological impact. Reported physical symptoms include elevated body temperature, blood sugar levels, heart rate, goosebumps, jaw clenching, dry mouth, and hyperreflexia. Adverse experiences may involve sensations of numbness, weakness, nausea, and tremors.

Psychological:

The immediate psychological effects of LSD are primarily characterized by visual hallucinations and illusions, often referred to colloquially as “trips.” The nature and intensity of these experiences depend on dosage and how it interacts with the individual’s brain. Trips typically commence within 20–30 minutes when ingested orally (even faster if snorted or injected), reach their peak three to four hours after ingestion, and can endure for up to 20 hours at high doses. Some users may also encounter an “afterglow,” a sustained improvement in mood or perceived mental state lasting for days or even weeks after ingestion in certain instances.

Positive or “good trips” are described as profoundly stimulating and enjoyable, characterized by intense joy, euphoria, heightened appreciation for life, reduced anxiety, a sense of spiritual enlightenment, and feelings of interconnectedness with the universe. Conversely, negative experiences, known as “bad trips,” induce a range of dark emotions, including irrational fear, anxiety, panic, paranoia, dread, distrust, hopelessness, and, in extreme cases, suicidal thoughts. While predicting a lousy trip is impossible, factors like mood, surroundings, sleep, hydration, social setting, and more can be managed (commonly referred to as “set and setting”) to minimize the risk of such an experience.

Sensory:

LSD induces an intense sensory experience, affecting perception, emotions, memories, time, and awareness for 6 to 20 hours, contingent on dosage and tolerance levels. Typically commencing within 30 to 90 minutes after ingestion, users may undergo a spectrum of perceptual alterations, ranging from subtle shifts to profound cognitive transformations. These alterations often encompass changes in auditory and visual perception.

Sensory effects may encompass experiences of more vibrant or radiant colors, objects appearing to ripple, “breathe,” or exhibit other forms of motion, the emergence of spinning fractals overlaying one’s vision, colored patterns visible with closed eyes, altered time perception, geometric patterns manifesting on textured surfaces, and object morphing. Additionally, food’s texture and taste might be perceived differently, potentially leading to aversions to foods typically enjoyed. Some users report that the inanimate world appears inexplicably, with static objects seeming to move relative to additional spatial dimensions. Many visual effects resemble phosphenes seen when applying pressure to the eyes and have been studied as form constants. Concentration, thoughts, emotions, or music can influence these effects and patterns. Auditory effects of LSD include echo-like distortions of sounds, heightened ability to discern concurrent hearing and visual stimuli, and an overall intensification of the music-listening experience. Higher doses may induce profound distortions of sensory perception, such as synesthesia, the perception of additional spatial or temporal dimensions, and temporary dissociation.

Adverse effects

Safety at Standard Dosages:

LSD, like other classical psychedelics, is generally considered physiologically safe when consumed at standard dosages (ranging from 50 to 200 micrograms, or μg). The primary concerns associated with psychedelics are primarily related to their psychological effects. A notable 2010 study by David Nutt in the UK, evaluating 20 drugs based on their individual and societal harm criteria, positioned LSD as one of the least harmful substances, approximately one-tenth as detrimental as alcohol.

Psychological:

Mental Disorders: LSD can potentially induce panic attacks or extreme anxiety, commonly called a “bad trip.” While population studies have not indicated a heightened incidence of mental illness among psychedelic drug users as a whole, and in fact, psychedelic users often exhibit lower rates of depression and substance abuse compared to control groups, there is evidence suggesting that individuals with severe mental conditions such as schizophrenia may be more susceptible to adverse reactions when using LSD. Reports have linked hallucinogens, including LSD, to the onset of psychiatric disorders such as psychosis and depression. However, these occurrences seem to be triggered in predisposed individuals and typically do not lead to illness in emotionally healthy individuals. Recent reports have also documented behavioral-related fatalities and suicides associated with LSD.

Suggestibility:

Although publicly available documents indicate that the CIA and the Department of Defense have discontinued research into the use of LSD for mind control, research from the 1960s suggests that individuals, both mentally ill and healthy, are more suggestible while under the influence of the substance.

Flashbacks: “Flashbacks” represent a psychological phenomenon wherein an individual re-experiences some of LSD’s subjective effects even after the drug’s effects have subsided. These flashbacks can persist for days or months after the use of hallucinogens. Individuals afflicted with hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (HPPD) may endure intermittent or chronic flashbacks, causing distress or impairment in their daily lives. The causes of the “flashback” phenomenon appear multifaceted, with some researchers attributing certain cases to somatic symptom disorder or associative reactions to contextual cues. Pre-existing psychopathologies may also contribute to these experiences. HPPD is considered rare, with estimates ranging from 1 in 20 users for type 1 HPPD to 1 in 50,000 users for the more concerning type 2 HPPD.

Contrary to online rumors claiming long-term storage of LSD in the spinal cord or other body parts, pharmacological evidence indicates that LSD has a short half-life of 175 minutes. It undergoes enzymatic metabolism into more water-soluble compounds, like 2-oxo-3-hydroxy-LSD, which are then eliminated through urine. There is no evidence supporting the notion of long-term LSD storage in the body.

Clinical evidence suggests that LSD-induced flashbacks can be potentiated by chronic use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), even months after discontinuing LSD use. 145

Drug Interactions:

Several psychedelics, including LSD, are metabolized by CYP2D6, and some SSRIs significantly inhibit CYP2D6. Therefore, co-administering SSRIs with LSD may increase the risk of serotonin syndrome (SS). 145 Chronic use of SSRIs, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) can diminish the subjective effects of psychedelics, likely due to SSRI-induced downregulation of 5-HT2A receptors and MAOI-induced desensitization of 5-HT2A receptors. 145 The interactions between psychedelics, antipsychotics, and anticonvulsants are not well-documented. Still, reports suggest that combining psychedelics with mood stabilizers like lithium may provoke seizures and dissociative effects in individuals with bipolar disorder. 146 Combining lithium with LSD has been reported to significantly intensify LSD reactions, potentially leading to acute comatose states.

Lethal Dose:

Researchers have estimated the lethal oral dose of LSD in humans to be 100 milligrams, based on reported LD50 and lethal blood concentrations observed in rodent studies.

Tolerance:

LSD demonstrates a significant tachyphylaxis phenomenon, with tolerance emerging within 24 hours after a single administration. However, the occurrence of tachyphylaxis at intervals shorter than 24 hours is not well understood. Reports suggest that after a single administration of LSD (or other psychedelics with cross-tolerance), three or four days of abstinence are required for tachyphylactic tolerance to return to baseline. Tolerance to LSD also develops with consistent use and has been shown to cross-tolerate with substances like mescaline, psilocybin, and, to some extent, DMT. Serotonin 5-HT2A receptor downregulation is believed to underlie LSD tolerance. Researchers propose that tolerance typically returns to baseline after two weeks of abstaining from psychedelics.

Addiction and Dependence Liability:

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) asserts that LSD is addictive, though most other sources argue otherwise, stating that it rarely leads to compulsive use. While it is readily abused, LSD does not typically result in addiction. In laboratory settings, there are no recorded instances of successfully training animals to self-administer LSD. Research indicates that although tolerance to LSD develops rapidly, a withdrawal syndrome does not appear, suggesting that the potential for a withdrawal syndrome does not necessarily correlate with the ability to acquire rapid tolerance to a substance. A comprehensive examination of substance use disorder based on the DSM-IV criteria noted that virtually no hallucinogens result in dependence, unlike psychoactive drugs from other classes like stimulants and depressants.

Cancer and Pregnancy:

The mutagenic potential of LSD remains unclear. Existing evidence tends to suggest limited or negligible effects at commonly used doses. Studies have failed to reveal evidence of the teratogenic or mutagenic effects of LSD use.

Overdose

Lack of Fatal Overdoses:

There are no documented cases of fatal human overdoses resulting from LSD consumption. However, it’s worth noting that there hasn’t been a comprehensive review on this subject since the 1950s, and there has been almost no legal clinical research on LSD since the 1970s. There have been instances where individuals mistakenly ingested an exceptionally high dose of LSD, believing it to be cocaine. In these cases, their blood plasma had LSD levels ranging from 1000 to 7000 micrograms per 100 milliliters of blood plasma. These individuals experienced comatose states, vomiting, respiratory problems, hyperthermia, and mild gastrointestinal bleeding. Fortunately, they survived and suffered no lasting effects after receiving medical attention.

Bad Trips and Excited Delirium:

Individuals undergoing a “bad trip” due to LSD intoxication may encounter severe anxiety, tachycardia, phases of psychotic agitation, and varying degrees of delusions, which can sometimes resemble excited delirium (ExDS). It’s important to note that individuals experiencing ExDS may suddenly die, but there are no reported cases of sudden death directly resulting from a bad trip. However, instances of death during a bad trip have been documented when individuals were subjected to prone maximal restraint (PMR) and positional asphyxia while restrained by law enforcement personnel.

Management of Massive Doses:

Massive LSD doses are primarily managed through symptomatic treatments, and agitation can be alleviated using benzodiazepines. Providing reassurance in a calm and secure environment is also beneficial. Antipsychotic agents like neuroleptics and haloperidol are generally not recommended as they may have adverse psychomimetic effects. Gastrointestinal decontamination with activated charcoal is usually ineffective due to LSD’s rapid absorption unless administered within 30 to 60 minutes of ingesting massive amounts. The administration of anticoagulants, vasodilators, and sympatholytics may help treat ergotism.

Designer Drug Overdose:

A significant concern is the prevalence of novel psychoactive substances, particularly those from the 25-NB (NBOMe) series like 25I-NBOMe and 25B-NBOMe, often sold disguised as LSD on blotter papers. These NBOMe compounds have been associated with life-threatening toxicity and fatalities. Fatalities linked to NBOMe intoxication indicate that many individuals unwittingly ingested substances they believed to be LSD. Researchers have pointed out that individuals familiar with LSD may wrongly assume safety when consuming NBOMe. It’s essential to note that the alleged physiological toxicity of LSD is likely due to psychoactive substances other than LSD itself. NBOMe compounds taste bitter and are not active when ingested orally, typically requiring sublingual administration. Numbness of the tongue and mouth, followed by a metallic chemical taste, is a common side effect of NBOMe compounds, differentiating them from LSD. While recreational doses of LSD have resulted in relatively low incidents of acute toxicity, NBOMe compounds have markedly distinct safety profiles. Testing for the presence of LSD can be done using Ehrlich’s reagent.

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics:

LSD exhibits varying binding affinities for different serotonin receptors, and its effects are primarily mediated through its interactions with these receptors. Notably, LSD has a strong affinity for several serotonin receptors, including 5-HT1A (Ki=1.1nM), 5-HT2A (Ki=2.9nM), 5-HT2B (Ki=4.9nM), 5-HT2C (Ki=23nM), 5-HT5A (Ki=9nM in cloned rat tissues), and 5-HT6 receptors (Ki=2.3nM). Notably, these affinities are above the brain concentration of approximately 10–20 nM, suggesting that many of these receptors are not significantly activated by typical recreational doses of LSD. Additionally, LSD has been found to activate dopamine D2 receptors, which may contribute to its psychoactive effects.

LSD is believed to increase glutamate release in the cerebral cortex, particularly in layers IV and V. This action is thought to lead to increased excitation in these brain regions. The drug also interacts with dopamine D2 receptors and enhances dopamine D2 receptor protomer recognition and signaling in D2–5-HT2A receptor complexes, which may play a role in its psychotropic effects. Furthermore, LSD’s interaction with serotonin receptors results in the preferential recruitment of β-arrestin over activating G proteins, leading to a unique pharmacological profile.

Pharmacokinetics:

The effects of LSD typically last between 6 and 12 hours, depending on various factors, including dosage, tolerance, and age[119]. Despite earlier research suggesting a shorter half-life, more recent and accurate findings indicate that LSD has an elimination half-life of approximately 3.6 hours, with a terminal half-life of about 8.9 hours. After oral administration of a 200 μg dose, peak plasma concentrations are reached at around 1.5 hours. LSD’s effects are closely correlated with its concentration in circulation over time, and no acute tolerance is observed during the experience.

Approximately 1% of the drug is eliminated unchanged in the urine, while 13% is excreted as the major metabolite known as 2-oxo-3-hydroxy-LSD (O-H-LSD) within 24 hours. The specific cytochrome P450 enzymes responsible for O-H-LSD formation are unknown, and whether O-H-LSD possesses pharmacological activity. LSD’s pharmacokinetics have been more comprehensively explored recently, shedding light on its absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion patterns.

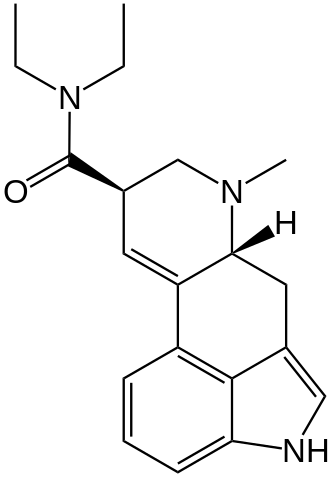

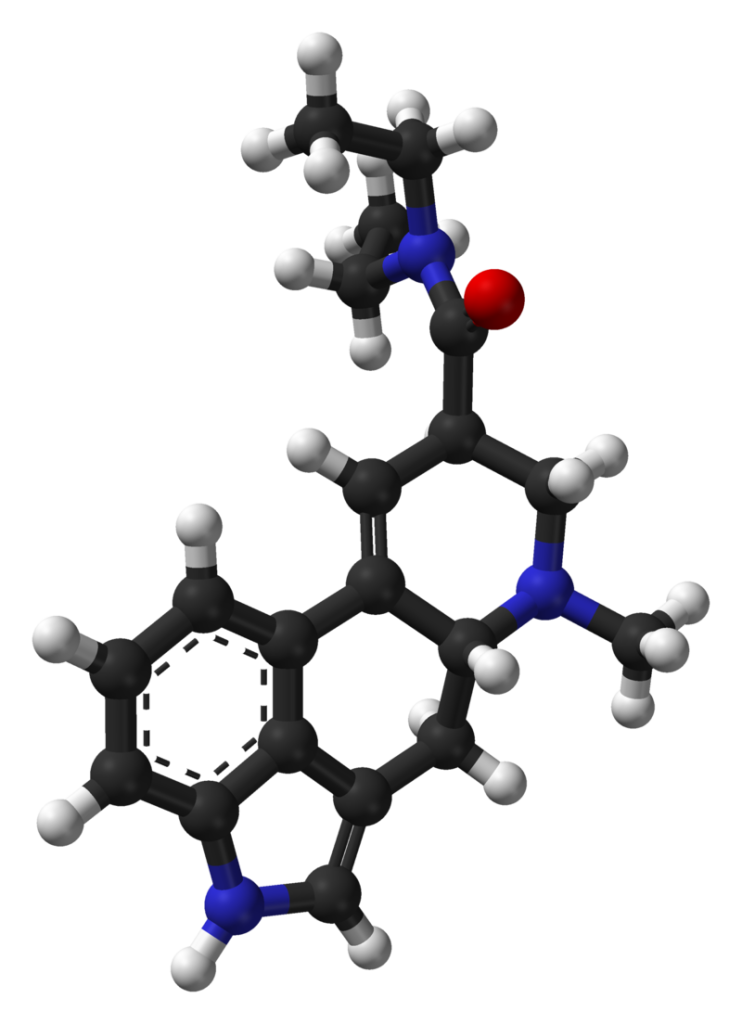

Chemistry

Chemical Properties: LSD is a chiral compound containing two stereocenters at carbon atoms C-5 and C-8, theoretically allowing for four different optical isomers of LSD. The specific isomer (+)-D-LSD has the absolute configuration (5R,8R). Interestingly, the C-5 isomers of lysergamides do not naturally occur and are not formed during the synthesis of d-lysergic acid. Retrosynthetically, the C-5 stereocenter shares the same configuration as the alpha carbon of the naturally occurring amino acid L-tryptophan, the precursor to all biosynthetic ergoline compounds.

However, it’s worth noting that LSD and iso-LSD, the two C-8 isomers, can rapidly interconvert in the presence of bases due to the acidic nature of the alpha proton. If formed during the synthesis, non-psychoactive iso-LSD can be separated by chromatography and subsequently isomerized to LSD.

Pure salts of LSD have the intriguing property of being triboluminescent, emitting small flashes of white light when subjected to mechanical agitation in the dark. Additionally, LSD is strongly fluorescent and exhibits a bluish-white glow when exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light.

Synthesis:

LSD, classified as an ergoline derivative, is typically synthesized by reacting diethylamine with an activated form of lysergic acid. Activating reagents for this process include phosphoryl chloride and peptide coupling reagents. Lysergic acid is derived from lysergamides like ergotamine, usually obtained from the ergot fungus cultivated on agar plates. It can also theoretically be synthesized from ergine (lysergic acid amide, LSA) found in morning glory seeds, although this approach is rare and impractical. Synthetic production of lysergic acid is possible but not commonly employed in clandestine manufacturing due to its low yields and high complexity.

Research:

Notably, lysergic acid, the precursor for LSD, has been successfully produced using genetically modified baker’s yeast.

Dosage:

LSD is measured in micrograms (µg), which are millionths of a gram. A typical single dose of LSD can range from 40 to 500 micrograms, approximately one-tenth the mass of a grain of sand. Threshold effects can be experienced with as little as 25 micrograms of LSD. The practice of using sub-threshold doses is known as microdosing[128].

Historically, the concentration of black market LSD distributed by Owsley Stanley in the mid-1960s was around 270 µg. During the 1970s, street samples varied from 30 to 300 µg. By the 1980s, the amount had decreased to approximately 100 to 125 µg, and further reductions occurred in the 1990s (20–80 µg range) and the 2000s.

Reactivity and Degradation:

LSD is a chemically fragile molecule, particularly vulnerable to degradation. It remains stable indefinitely in stable conditions—away from light, air, cold, and water. However, it has labile protons at C5 and C8, making these centers susceptible to epimerization. The C8 proton, influenced by the electron-withdrawing carboxamide attachment, is especially labile. The C5 proton’s removal is facilitated by the nitrogen’s electron-withdrawing effects and its pi-electron delocalization with the indole ring.

LSD also exhibits enamine-type reactivity due to the electron-donating influence of the indole ring. It is highly reactive to chlorine, which destroys LSD molecules on contact. Even tap water, containing minimal chlorine, can cause LSD to degrade when dissolved. The double bond between the 8-position and the aromatic ring is susceptible to nucleophilic attacks by water or alcohol, especially when exposed to UV light. This process often results in converting LSD to “lumi-LSD,” which is inactive in humans.

Stability studies have shown that LSD concentrations in urine remain relatively stable for up to four weeks at 25°C but exhibit a 30% loss at 37°C and up to 40% at 45°C after four weeks of incubation. The presence of metal ions in urine or buffer solutions can catalyze LSD decomposition, a process mitigated by adding EDTA.

Detection:

LSD can be detected using Ehrlich’s reagent, which turns purple upon reaction with the compound. This reagent is commonly used for field testing.

In laboratory settings, LSD can be quantified in urine, plasma, serum, or whole blood as part of drug abuse testing, poisoning diagnosis, or forensic investigations. LSD and its major metabolite are unstable in biofluids when exposed to light, heat, or alkaline conditions. As a result, specimens are protected from light, stored at low temperatures, and analyzed promptly to minimize losses.

History

LSD, synthesized initially on November 16, 1938, by Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann at Sandoz Laboratories in Basel, Switzerland, emerged from a comprehensive research program focused on exploring medically valuable derivatives of ergot alkaloids. The acronym “LSD” derives from the German “Lysergsäurediethylamid.”

The profound psychedelic properties of LSD were serendipitously discovered by Hofmann himself five years later, following an accidental ingestion of an unknown quantity of the chemical in 1943. Subsequently, Hofmann intentionally consumed 250 µg of LSD on April 19, 1943, anticipating this to be a threshold dose based on dosages of other ergot alkaloids. To his surprise, the effects he experienced were far more potent than he had anticipated. Sandoz Laboratories introduced LSD as a psychiatric medication in 1947, marketing it as a panacea for psychiatric disorders, from schizophrenia to criminal behavior, ‘sexual perversions,’ and alcoholism. Sandoz even provided the drug-free of charge to researchers investigating its effects.

During the 1950s, the United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) initiated Project MKUltra, an extensive research program. As part of this project, the CIA purchased the entire global supply of LSD for $240,000. The agency then distributed LSD through front organizations to American hospitals, clinics, prisons, and research institutions, conducting experiments that included administering the substance to a wide range of subjects without their knowledge, such as CIA employees, military personnel, medical professionals, sex workers, individuals with mental health conditions, and members of the general public. These experiments aimed to study their reactions and behaviors. The project was eventually exposed in the 1975 US Congressional Rockefeller Commission report.

In 1963, the Sandoz patents for LSD expired, leading to the production of the substance by the Czech company Spofa. Sandoz ceased its production and distribution in 1965.

The 1960s witnessed the emergence of several influential figures, including Aldous Huxley, Timothy Leary, and Al Hubbard, who began advocating for LSD. LSD became a focal point of the counterculture movement during this era. Early in the 1960s, the consumption of LSD and other hallucinogens was promoted by proponents of consciousness expansion, such as Leary, Huxley, Alan Watts, and Arthur Koestler. According to L. R. Veysey, these figures profoundly shaped the mindset of the new youth generation.

On October 24, 1968, the United States made possession of LSD illegal[146]. The last FDA-approved study involving LSD in patients concluded in 1980, while a study involving healthy volunteers was conducted in the late 1980s. Legally sanctioned and regulated psychiatric use of LSD persisted in Switzerland until 1993.

In November 2020, Oregon became the first US state to decriminalize the possession of small amounts of LSD following voters’ approval of Ballot Measure 110.

Legal status

The United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances, established in 1971, mandates signatory nations to prohibit LSD. Consequently, LSD is illegal in all countries parties to this convention, including the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and most of Europe. However, the enforcement of these laws varies from one country to another. Importantly, medical and scientific research involving LSD in human subjects is permitted under the provisions of the 1971 UN Convention.

Australia: LSD is classified as a Schedule 9 prohibited substance in Australia according to the Poisons Standard (February 2017). This classification designates substances that have the potential for abuse or misuse, and their manufacture, possession, sale, or use is prohibited by law unless required for medical or scientific research, analytical, teaching, or training purposes with approval from Commonwealth and State or Territory Health Authorities. In Western Australia, specific laws exist regarding possession, with differing thresholds for trial and presumptions of intent or trafficking based on the quantity.

Canada: In Canada, LSD is categorized as a controlled substance under Schedule III of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act. Anyone who attempts to obtain LSD without disclosing authorization 30 days before getting another prescription from a practitioner can be charged with an indictable offense, potentially resulting in imprisonment for up to 3 years. Possession with the intent to traffic is also considered an indictable offense and can lead to a prison sentence of up to 10 years.

United Kingdom: In the United Kingdom, LSD is classified as a Schedule 1 Class “A” drug. This classification signifies that it has no recognized legitimate uses. Possession of LSD without a license can result in a maximum sentence of 7 years’ imprisonment and an unlimited fine. At the same time, trafficking is punishable by life imprisonment and an unlimited fine, as per the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. In 2000, the UK Police Foundation’s Runciman Report recommended the transfer of LSD from Class A to Class B, but this recommendation did not change classification.

United States: LSD is categorized as Schedule I in the United States under the Controlled Substances Act of 1970. This classification signifies that LSD is illegal to manufacture, purchase, possess, process, or distribute without a Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) license. The DEA considers LSD to have a high potential for abuse, no legitimate medical use, and unsafe for use even under medical supervision. The amount of LSD one possesses can lead to different charges in the US, with distinctions between the total mass of the drug and its medium often taken into account for sentencing, as established in the 1995 United States Supreme Court case Neal v. United States. LSD precursors, lysergic acid, and lysergic acid amide are classified under Schedule III of the Controlled Substances Act.

Mexico: In Mexico, possessing small amounts of LSD for immediate consumption and personal use was decriminalized in April 2009 by the 2008 Constitution of Ecuador. However, restrictions apply, such as maintaining a distance of 300 meters from schools, police departments, or correctional facilities when possessing drugs.

Czech Republic: In the Czech Republic, possessing a “larger than small” amount of LSD for personal use was criminalized as of January 1, 1999, to align with international drug regulations. Small amounts for personal use are treated as a misdemeanor and subject to fines.

Ecuador: The 2008 Constitution of Ecuador views drug consumption as a health concern rather than a crime. The State Drugs Regulatory Office CONSEP has established maximum quantities for personal possession of drugs, including LSD.

This text provides a comprehensive overview of the legal status of LSD in various countries and regions. It highlights the variations in drug laws and regulations about LSD worldwide.

Research

Several organizations, including the Beckley Foundation, MAPS (Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies), Heffter Research Institute, and the Albert Hofmann Foundation, are dedicated to funding, promoting, and coordinating research into the potential medicinal and spiritual applications of LSD and related psychedelics. Notably, new clinical trials involving LSD and human subjects commenced in 2009 after a hiatus of 35 years. However, researching potential medical uses of LSD remains challenging due to its legal status in many parts of the world.

In 2001, the United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) stated that LSD did not produce aphrodisiac effects, enhance creativity, offer lasting positive outcomes for treating alcoholism or criminal behavior, induce a “model psychosis,” or generate immediate personality changes. More recent experimental applications of LSD have explored its potential in treating alcoholism and alleviating pain, particularly in cluster headaches, and as a subject of prospective studies for depression. There is accumulating evidence suggesting that psychedelics like LSD may induce molecular and cellular adaptations associated with neuroplasticity, potentially contributing to their therapeutic benefits.

Psychedelic therapy, also known as psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, gained attention in the 1950s and 1960s, with LSD used in psychiatry to enhance psychotherapeutic sessions. Some practitioners believed that LSD could assist patients in overcoming repressed subconscious material and treating conditions such as alcoholism. Ronald A. Sandison, for example, employed LSD in psychotherapy at Powick Hospital in England. One study emphasized the therapeutic value of the LSD experience in promoting self-acceptance and self-surrender, presumably by facilitating the confrontation of personal issues and psychological problems. Nonetheless, recent reviews have highlighted methodological flaws in early trials, including the absence of adequate control groups, limited follow-up, and vague criteria for assessing therapeutic outcomes, casting doubt on the reliability of their findings. Modern organizations like MAPS have revitalized clinical research on LSD, especially in anxiety treatment.

In the 1950s and 1960s, some psychiatrists, like Oscar Janiger, explored the potential influence of LSD on creativity. They conducted experimental studies to measure LSD’s impact on creative activity and aesthetic appreciation. Dr. James Fadiman’s 1966 study explored how psychedelics could facilitate problem-solving and used LSD as a critical element in the research.

Since 2008, ongoing research has investigated the potential of LSD to alleviate anxiety in terminally ill cancer patients grappling with impending deaths. A 2012 meta-analysis discovered that a single dose of LSD, in conjunction with various alcoholism treatment programs, led to a reduction in alcohol abuse that persisted for several months. However, no effect was observed after one year. Adverse events included seizures, moderate confusion and agitation, nausea, vomiting, and unusual behavior.

Furthermore, recent studies have revealed that LSD possesses potent psychoplastogenic properties, meaning it can promote rapid and sustained neural plasticity, potentially offering a broad range of therapeutic benefits. Evidence has shown that LSD can increase markers of neuroplasticity in human brain organoids and enhance memory performance in human subjects. Additionally, LSD may exhibit analgesic properties relevant to pain management in terminally ill patients, addressing phantom pain and potentially serving as a treatment for inflammatory diseases like rheumatoid arthritis.

FAQ

1. What is LSD?

LSD, or Lysergic Acid Diethylamide, is a powerful hallucinogenic substance known for its mind-altering effects. It’s derived from ergot, a fungus that grows on rye and other grains. LSD is famous for inducing vivid and intense sensory experiences, altered perceptions, and hallucinations.

2. How is LSD typically consumed?

LSD is commonly found in the form of small, colorful squares of paper known as “blotter acid.” It can also be taken as a liquid or as gelatin squares. The most common method of consumption is by ingesting it orally, often by placing a blotter paper on the tongue until it dissolves.

3. What are the effects of LSD?

LSD’s effects can vary widely but often include visual hallucinations, distorted perceptions of time, sensory enhancement, and profound alterations in thought and consciousness. These effects typically last for 6 to 12 hours.

4. Is LSD legal?

The legal status of LSD varies by country. In many nations, including the United States, it is classified as a Schedule I controlled substance, making it illegal to possess, manufacture, or distribute.

5. Can LSD be used for medical or therapeutic purposes?

Research into the therapeutic potential of LSD has been ongoing, with some studies suggesting it may have applications in treating conditions like depression, anxiety, and alcoholism. However, due to its legal status, further research is limited in many places.

6. What are the risks associated with LSD use?

LSD use carries several risks, including the potential for “bad trips,” which can lead to extreme anxiety and fear. It can also impair judgment and coordination, increasing the risk of accidents. In some cases, LSD use can trigger lasting psychological issues.

7. Can LSD be addictive?

LSD is not considered physically addictive, and tolerance to its effects develops rapidly, making it challenging to use frequently. However, some individuals may develop a psychological dependence on the drug.

8. What precautions should be taken when using LSD?

If you are in a place where LSD use is legal and you choose to use it, it’s essential to be in a safe and comfortable environment, ideally with a trusted and sober friend as a “trip sitter.” Also, be aware of the potential risks and psychological effects.

9. Can LSD be detected in drug tests?

Standard drug tests, such as urine tests, do not typically screen for LSD. However, specialized tests can detect its presence. It’s crucial to be aware of your local drug testing laws and workplace policies.

10. Is microdosing LSD safe?

Microdosing involves taking small, sub-perceptual amounts of LSD regularly. Some people claim it enhances creativity and productivity while minimizing the risks associated with larger doses. However, the long-term safety of microdosing is not well-established, and individual responses may vary.

11. How long does LSD stay in your system?

The effects of a standard LSD dose can last 6 to 12 hours, but the drug can be detectable in urine for up to 2-4 days and in hair follicles for several months after use.

12. Can LSD cause permanent damage or psychosis?

While LSD does not typically cause permanent physical damage, it can lead to long-lasting psychological effects, especially in individuals with a predisposition to mental health issues. Prolonged or high-dose use may increase the risk of persistent hallucinogen-induced perceptual disorder (HPPD).

Remember that LSD use has legal, health, and safety implications. If you are considering using LSD or have concerns about its effects, it’s essential to seek information and, if necessary, consult with a healthcare professional.

References

- In the realm of chemistry, the term “amide” finds its definition, as per Collins English Dictionary. This definition can be traced back to an archived source dating to April 2, 2015, and was retrieved on January 31, 2015.

- A similar definition of “amide” can be found in the American Heritage Dictionary, accessible at ahdictionary.com. The source is archived from its original version on April 2, 2015, and was retrieved on January 31, 2015.

- Oxford Dictionary offers yet another perspective on the definition of “amide” in English. This source, found at oxforddictionaries.com, was also archived on April 2, 2015, and retrieved on January 31, 2015.

- Exploring a different dimension, the pharmacological world delves into the topic of “Hallucinogen Abuse and Dependence.” This in-depth discussion can be found in “Encyclopedia of Psychopharmacology A Springer Live Reference,” edited by Price LH and Stolerman IP. It is published by Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg in Heidelberg, Germany, and spans pages 1 to 5. The reference was made on June 7, 2014, and bears the DOI: 10.1007/978-3-642-27772-6_43-2. Its ISBN is 978-3-642-27772-6.

- The complexities of hallucinogen abuse and dependence, particularly in relation to LSD and psilocybin, are further examined in this academic text: “Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.),” authored by Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, and Hyman SE. Published by McGraw-Hill Medical in New York in 2009, it encompasses Chapter 15, specifically page 375. The ISBN for this reference is 9780071481274.

- Diving into the pharmacokinetics and concentration-effect relationship of oral LSD in humans, “The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology” offers insights in its June 2015 edition, Volume 19 (1), on page pyv072. The research was conducted by Dolder PC, Schmid Y, Haschke M, Rentsch KM, and Liechti ME. It carries the DOI: 10.1093/ijnp/pyv072 and a PubMed ID of 26108222.

- Passie T, Halpern JH, Stichtenoth DO, Emrich HM, and Hintzen A explore “The pharmacology of lysergic acid diethylamide” in a comprehensive review published in “CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics.” This article can be found in Volume 14 (4), spanning pages 295 to 314, and was published in 2008. Its DOI is 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2008.00059.x, and it carries a PubMed ID of 19040555.

- “Adolescent Health Care: A Practical Guide,” authored by Neinstein LS and published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, delves into various facets of adolescent health care. On page 931 of this book, insights related to the topic can be found. The book is available in its original form and was retrieved on January 27, 2017.

- An intriguing journey through the history of lysergic acid diethylamide is presented in “From Psychiatry to Flower Power and Back Again: The Amazing Story of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide,” an article authored by Mucke HA. This article is featured in “Assay and Drug Development Technologies,” Volume 14 (5), spanning pages 276 to 281, and was published in July 2016. Its DOI is 10.1089/adt.2016.747, and it bears a PubMed ID of 27392130.

- For those delving into addiction psychopharmacology, “Clinical Manual of Addiction Psychopharmacology” proves to be a valuable resource. Authored by Kranzler HR and Ciraulo DA, this manual offers insights on page 216. It was published on April 2, 2007, and has an ISBN of 9781585626632.

- For detailed chemical information about LSD, the resource “Lysergide” can be accessed at pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- The world of psychedelics is explored in depth in “Pharmacological Reviews,” specifically in Volume 68 (2). Edited by Barker EL and authored by Nichols DE, this publication spans pages 264 to 355 and was released in April 2016. Its DOI is 10.1124/pr.115.011478, and it carries a PubMed ID of 26841800.

- The National Institute of Drug Abuse provides valuable insights into “What are hallucinogens?” This resource, dated January 2016, is archived from the original and was retrieved on April 24, 2016.

- “Hallucinations Under Psychedelics and in the Schizophrenia Spectrum: An Interdisciplinary and Multiscale Comparison” is an article published in “Schizophrenia Bulletin.” This interdisciplinary exploration is featured in Volume 46 (6), spanning pages 1396 to 1408, and was published in December 2020. The DOI for this article is 10.1093/schbul/sbaa117, and it carries a PubMed ID of 32944778.

- A comprehensive study on the acute dose-dependent effects of lysergic acid diethylamide in healthy subjects is detailed in “Neuropsychopharmacology,” Volume 46 (3). Authored by Holze F, Vizeli P, Ley L, Müller F, Dolder P, Stocker M, et al., this study can be found on pages 537 to 544 and was published in February 2021. Its DOI is 10.1038/s41386-020-00883-6, and it has a PubMed ID of 33059356.

- For an extensive profile of LSD, encompassing its chemistry, effects, other names, synthesis, mode of use, pharmacology, medical use, and control status, refer to “LSD profile” available at EMCDDA. This resource is archived from the original and was accessed on April 28, 2021.

- The article “This is Why You Can’t Escape an Hours-Long Acid Trip” offers insights into the lasting effects of LSD. Authored by Sloat S, this article was published on January 27, 2017, and is available in its archived form.

- Liechti ME, Dolder PC, and Schmid Y investigate “Alterations of consciousness and mystical-type experiences after acute LSD in humans” in the journal “Psychopharmacology.” This study is featured in Volume 234 (9–10), spanning pages 1499 to 1510, and was published in May 2017. The DOI for this study is 10.1007/s00213-016-4453-0, and it carries a PubMed ID of 27714429.

- “How LSD Went From Research to Religion” is an intriguing exploration of the history of LSD, authored by Gershon L. This article was published on July 19, 2016, and is available in its archived form.

- “Acid dreams: the complete social history of LSD: the CIA, the Sixties, and beyond” is a book authored by Lee MA and Shlain B. It offers an extensive social history of LSD and is available in its original form. The ISBN for this book is 0-8021-3062-3.

- “Psychopharmacology,” a book by Ettinger RH, provides valuable insights into the field. On page 226, it contributes to the understanding of psychopharmacology. This book is available in its archived form and was retrieved on September 27, 2021.

- An intriguing glimpse into “Psychiatric Research with Hallucinogens” is offered on druglibrary.org. This resource is available in its original form and was retrieved on July 26, 2021.

- The potential use of d-lysergic acid diethylamide in the treatment of alcoholism is explored in “Use of d-lysergic acid diethylamide in the treatment of alcoholism,” an article published in the “Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol.” This article is featured in Volume 20 (3), spanning pages 577 to 590, and was published in September 1959. Its DOI is 10.15288/qjsa.1959.20.577, and it carries a PubMed ID of 13810249.

- Krebs TS and Johansen PØ delve into “Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) for alcoholism” in their meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. This study is available in the “Journal of Psychopharmacology,” published on July 2012, and has a DOI of 10.1177/0269881112439253. Its PubMed ID is 22406913.

- In the annals of the United States Congress, discussions surrounding “Increased Controls Over Hallucinogens and Other Dangerous Drugs” took place in 1968. These discussions are documented in the congressional record, featuring H.R. 14096 and H.R. 15355. The discussions transpired on February 19, 26, 276, and March 19, 1968.

- The National Institute on Drug Abuse offers valuable information on “Hallucinogens” in its InfoFacts section. This resource is available in its original form and was retrieved on November 21, 2009.

- A study on the trends in LSD use among U.S. adults from 2015 to 2018 is presented in “Trends in LSD use among US adults: 2015–2018,” authored by Yockey RA, Vidourek RA, and King KA. This study was published in Drug and Alcohol Dependence in July 2020 and has a PubMed ID of 32450479. Its DOI is 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108071.

- The National Institute on Drug Abuse provides a comprehensive overview of “Hallucinogens – LSD, Peyote, Psilocybin, and PCP” in its DrugFacts section. This resource is available in its original form and was published in December 2014.

- “Alcohol and Drugs in North America: A Historical Encyclopedia,” edited by Fahey D and Miller JS, encompasses a wealth of historical information. On page 375, it offers insights into the subject matter. The ISBN for this encyclopedia is 978-1-59884-478-8.

- The San Francisco Chronicle, dated September 20, 1966, sheds light on various facets of the era, including the use of LSD.

- “Realms of the Human Unconscious (Observations from LSD Research),” authored by Grof S and Grof JH, offers an intriguing exploration of the human unconscious. The book, published by Souvenir Press (E & A) Ltd., features insights on pages 13 to 14. Its ISBN is 978-0-285-64882-1.

- Nutt DJ, King LA, and Nichols DE discuss the “Effects of Schedule I drug laws on neuroscience research and treatment innovation” in “Nature Reviews. Neuroscience.” This article was published in August 2013 and has a DOI of 10.1038/nrn3530. Its PubMed ID is 23756634.