- 1 Unlocking the Potential of Ethylphenidate – Buying Tips and Safety Insights

- 2 The Appeal of Ethylphenidate Products

- 3 How to Buy Ethylphenidate Safely

- 4 Why Choose Ethylphenidate?

- 5 Start Your Ethylphenidate Journey

- 6 SUMMARY

- 7 Chemistry

- 8 Pharmacology

- 9 Subjective effects

- 10 Toxicity

- 11 Legal status

- 12 FAQ

- 12.1 1. What is Ethylphenidate?

- 12.2 2. What are the Effects of Ethylphenidate?

- 12.3 3. Is Ethylphenidate Legal?

- 12.4 4. How is Ethylphenidate Typically Used?

- 12.5 5. What Are the Potential Risks and Side Effects of Ethylphenidate?

- 12.6 6. Is Ethylphenidate Safe to Use?

- 12.7 7. Can Ethylphenidate Be Used Recreationally or for Research Purposes?

- 12.8 8. Is Ethylphenidate Addictive?

- 12.9 9. Can Ethylphenidate Be Combined with Other Substances?

- 12.10 10. Where Can I Find More Information About Ethylphenidate?

- 13 References

Unlocking the Potential of Ethylphenidate – Buying Tips and Safety Insights

When it comes to synthetic stimulants, Ethylphenidate remains a popular choice for those seeking powerful, fast-acting effects. With a growing number of marketplaces offering Ethylphenidate for sale, knowing how to safely and effectively purchase this compound is crucial. Whether you’re looking to buy Ethylphenidate online USA, explore options for Ethylphenidate Canada, or research Ethylphenidate vendors, understanding the product and market will help you make informed decisions.

The Appeal of Ethylphenidate Products

Ethylphenidate has gained traction for its distinctive properties and effectiveness, making it a go-to stimulant for research and other uses. Enthusiasts can explore various options, including Ethylphenidate powder, Ethylphenidate research chemicals, and more, ensuring preferences are met. For those looking to order Ethylphenidate, trusted platforms provide access to both local and international markets like buy Ethylphenidate Australia or purchase Ethylphenidate in the USA.

Accessibility is another key draw. With platforms specializing in buy Ethylphenidate credit card transactions and Ethylphenidate online shops, finding a reliable source has never been easier. Vendors often ensure discrete shipping, a critical requirement for many buyers, especially when sourcing products like Ethylphenidate bath salts or research compounds.

How to Buy Ethylphenidate Safely

Navigating the market requires careful planning to ensure both safety and quality. If you’re considering buy Ethylphenidate, keep these tips in mind:

- Prioritize Trusted Vendors

Look for well-reviewed sellers with a strong reputation in the synthetic stimulant community. Keywords like Ethylphenidate shop and Ethylphenidate USA suppliers often guide you to vendors who offer reliable products.

- Consider Product Purity

Whether you’re buying research chemicals or Ethylphenidate powder, verify the purity level. Detailed product descriptions and lab testing transparency are signs of a trustworthy supplier.

- Global Accessibility

Many suppliers cater to international needs, allowing options for buy Ethylphenidate Canada, buy Ethylphenidate China, and beyond. Ensure the vendor offers secure and efficient shipping for a seamless purchasing experience.

- Secure Payment Methods

Vendors that allow payment via credit card or other secure methods simplify the buying process while ensuring transactions are safe.

Why Choose Ethylphenidate?

Ethylphenidate appeals to a diverse audience due to its powerful effects and availability in different forms. Whether you prefer Ethylphenidate buy online bundles or smaller, custom quantities, the variety ensures options for every buyer. Furthermore, the wide-reaching capabilities of Ethylphenidate online shops mean that products can be sourced with ease, whether you’re based in the USA, Canada, or abroad.

The market also continues to expand with more vendors, increasing competition and offering better prices on products like Ethylphenidate crystals, research compounds, and stimulants for study. Frequently, sales and quality-focused shops make it easier to securely buy Ethylphenidate online without compromising on standards.

Start Your Ethylphenidate Journey

For buyers ready to explore Ethylphenidate for sale, the opportunities are vast. Finding the right vendor is key to ensuring a safe, smooth purchasing experience. Always prioritize transparency, secure payment processes, and detailed product labeling when you order Ethylphenidate online. Explore your options today and see how purchase Ethylphenidate through trusted suppliers enhances your confidence and convenience.

SUMMARY

Ethylphenidate, also called EPH, is a recently developed stimulant compound belonging to the phenidate class. When consumed, it induces typical stimulant effects.

This substance closely resembles methylphenidate, a well-known stimulant available under brand names like Ritalin and Concerta. Although both substances operate through similar pharmacological pathways, users often distinguish them by their distinct subjective effects, with methylphenidate frequently associated with recreational use.

Ethylphenidate is predominantly disseminated as a research chemical, primarily through online vendors. This distribution method is primarily attributed to its ambiguous legal status in certain countries, existing in a grey area.

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| showIUPAC name | |

| CAS Number | 57413-43-1 |

| PubChem CID | 3080846 |

| ChemSpider | 2338571 |

| UNII | 984DG861KD |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID60912317 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C15H21NO2 |

| Molar mass | 247.338 g·mol−1 |

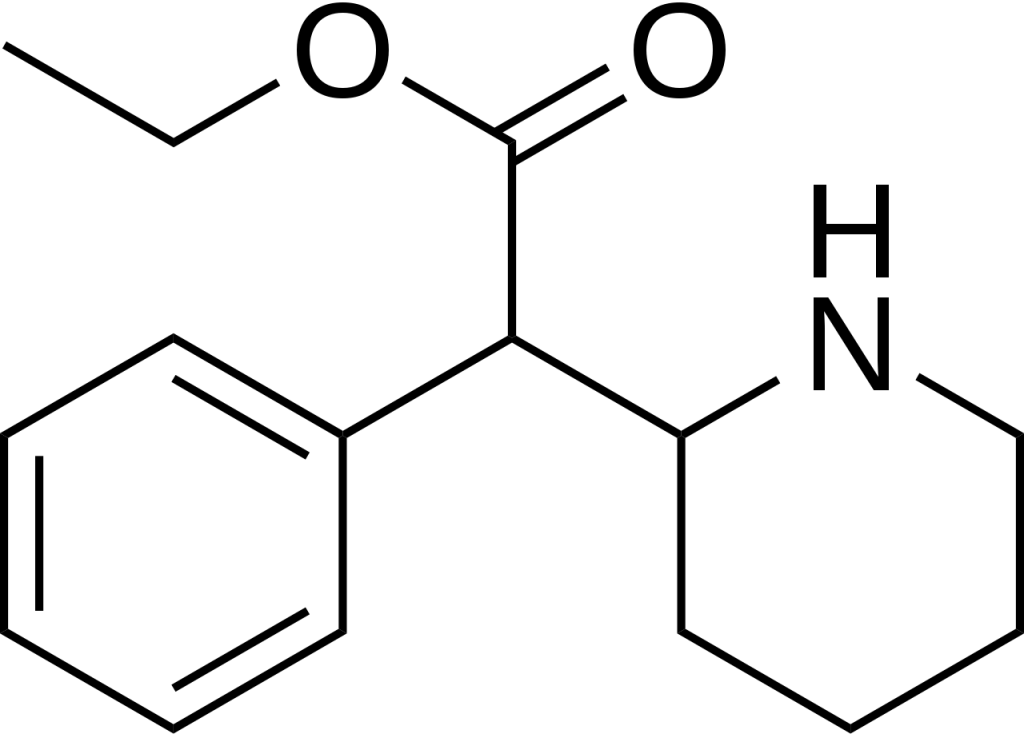

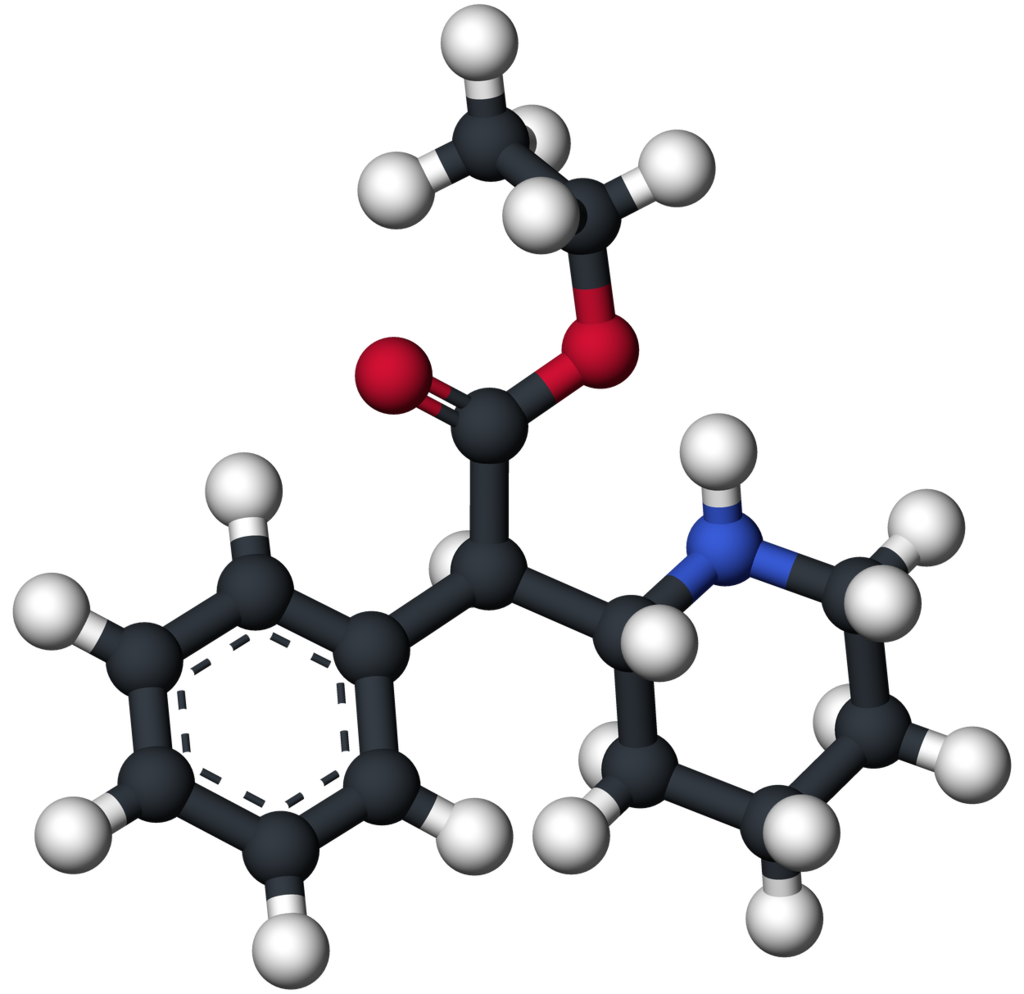

Chemistry

Ethylphenidate is a synthetic compound classified within the substituted phenethylamine and substituted phenidate families. Its molecular structure comprises a phenethylamine core featuring a phenyl ring connected to an amino (-NH2) group via an ethyl chain. Regarding structural similarity, it resembles amphetamine, with a substitution at the Rα position, leading to the incorporation of a piperidine ring terminating at the terminal amine of the phenethylamine chain. Additionally, it incorporates an ethyl acetate group attached to the Rβ position within its structure. Notably, Ethylphenidate distinguishes itself from methylphenidate by having an elongated carbon chain. The nomenclature breaks down as follows: “Ethyl-” signifies the presence of a side chain with two carbon atoms, “Phen-” represents the phenyl ring, “id-” indicates the contraction from a piperidine ring, and “-ate” denotes the acetate group encompassing the oxygen atoms. It’s important to note that Ethylphenidate is a chiral compound, and it is likely produced as a racemic mixture containing equal amounts of both enantiomers.

Pharmacology

Ethylphenidate exerts its effects by functioning as both a dopamine reuptake inhibitor and a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. This means it effectively enhances dopamine and norepinephrine neurotransmitters in the brain by attaching to and partially obstructing the transporter proteins responsible for removing these monoamines from the synaptic cleft. Consequently, this mechanism permits the accumulation of dopamine and norepinephrine within the brain, giving rise to stimulating and euphoric effects.

All available information concerning the pharmacokinetics of methylphenidate is derived from studies conducted on rodents. These studies have revealed that methylphenidate exhibits a higher degree of selectivity toward the dopamine transporter (DAT) when compared to methylphenidate, with approximately the same efficacy as the parent compound. However, it displays considerably less activity on the norepinephrine transporter (NET). Its dopaminergic pharmacodynamic profile closely resembles methylphenidate and is primarily responsible for its euphoric and reinforcing effects.

Below is the binding profile of ethylphenidate in mice alongside that of methylphenidate. The figures for both the racemic and dextrorotary enantiomers are provided for reference:

| Compound | Binding DAT | Binding NET | Uptake DA | Uptake NE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| d-methylphenidate | 139 | 408 | 28 | 46 |

| d-ethylphenidate | 276 | 2479 | 24 | 247 |

| dl-methylphenidate | 105 | 1560 | 24 | 31 |

| dl-ethylphenidate | 382 | 4824 | 82 | 408 |

Ethylphenidate can be generated endogenously in the body, primarily in the liver, through the concurrent ingestion of alcohol and methylphenidate. This phenomenon is most prevalent when substantial quantities of methylphenidate and alcohol are ingested concurrently, typically in scenarios unrelated to medical use or during overdose situations. A similar metabolic process is recognized to transpire when cocaine and alcohol are consumed in tandem, giving rise to cocaethylene. However, it’s important to note that only a small fraction of the ingested methylphenidate, typically a few per cent, undergoes conversion into methylphenidate through this route. As a result, producing a pharmacologically significant dose with observable physiological effects is highly improbable.

Subjective effects

The typical mental state induced by methylphenidate is often marked by intense mental stimulation, heightened focus, and profound euphoria. It encompasses a wide array of typical cognitive effects associated with stimulants. While adverse effects are generally mild at lower to moderate doses, their likelihood increases substantially with higher quantities or prolonged usage, especially during the comedown phase of the experience.

Please note that the effects outlined below are based on the Subjective Effect Index (SEI), derived from anecdotal user reports and personal analyses of contributors to PsychonautWiki. Therefore, they should be approached with a degree of scepticism.

Acknowledging that these effects may not necessarily manifest predictably or consistently is essential. However, higher doses are more likely to produce the full spectrum of effects and the potential for adverse consequences, including addiction, severe harm, or even fatality ☠.

Physical:

- Stimulation: Ethylphenidate is generally reported as providing a distinct but less potent form of energy and stimulation compared to amphetamine or methamphetamine, yet stronger than that of modafinil or caffeine. Lower to moderate doses enhance overall productivity, while higher doses encourage physical activities such as dancing, socializing, running, or cleaning. This stimulation can be forceful, making it difficult to remain still at higher doses, resulting in jaw clenching, involuntary bodily shakes, and vibrations, leading to pronounced bodily tremors, hand instability, and a general loss of fine motor control.

- Dehydration

- Appetite suppression

- Vasoconstriction[citation needed]: Prolonged use of methylphenidate, due to norepinephrine reuptake inhibition, strains the cardiovascular system by causing sympathetic nervous system-induced vessel constriction.

- Increased heart rate[citation needed]

- Increased blood pressure[citation needed]

- Teeth grinding

Cognitive:

- Focus enhancement: Ethylphenidate’s ability to enhance focus is most pronounced at lower to moderate doses, as higher amounts may impair concentration.

- Euphoria: The euphoric rush associated with methylphenidate use, stemming from dopamine reuptake inhibition, is brief and compulsive, similar to that induced by cocaine.

- Time distortion: This effect entails perceiving time passing much faster than usual, as if time were speeding up.

- Thought acceleration

- Analysis enhancement

- Wakefulness

- Motivation enhancement

- Increased music appreciation

After:

The effects during the comedown phase of a stimulant experience are generally less pleasant and may feel negative compared to those experienced during the peak. This phase, often referred to as a “comedown,” arises due to neurotransmitter depletion and typically involves:

- Anxiety

- Cognitive fatigue

- Depression

- Irritability

- Motivation suppression

- Thought deceleration

- Wakefulness

Toxicity

The toxicity and long-term health consequences of recreational ethylphenidate use have not been comprehensively examined within a scientific context, and the precise toxic dosage remains uncertain. This ambiguity arises from the limited historical usage of ethylphenidate by humans.

Anecdotal reports from individuals within the community who have experimented with ethylphenidate suggest that trying this substance at low to moderate doses, used sparingly and in isolation, does not appear to be associated with negative health effects. However, it is essential to exercise caution and acknowledge that no guarantees can be provided.

It is worth noting that ethylphenidate crystals possess abrasive properties and can be somewhat caustic to mucous membranes. Reckless administration can lead to the deterioration of chosen routes of intake. Therefore, it is crucial to practice routine maintenance, such as pre-soaking the sinus cavity with water before and after insufflation to mitigate potential damage.

Inhaling ethylphenidate may irritate lung tissue, resulting in increased phlegm production and an irritated cough.

To ensure safety, it is strongly recommended that harm reduction practices be employed when using this substance.

Tolerance and Addiction Potential:

Similar to other stimulants, chronic ethylphenidate use carries a moderate risk of addiction and a high potential for misuse, leading to psychological dependence in certain individuals. Those who develop an addiction may experience cravings and withdrawal effects if they abruptly cease usage.

Tolerance to many of ethylphenidate’s effects develops with prolonged and repeated use. Consequently, users may find themselves needing to administer increasingly larger doses to achieve the same effects. After ceasing consumption, it typically takes approximately 3 to 7 days for tolerance to diminish by half and 1 to 2 weeks to return to baseline in the absence of further usage. Importantly, ethylphenidate induces cross-tolerance with all other dopaminergic stimulants, meaning that consumption of ethylphenidate diminishes the effects of all stimulants.

Psychosis:

Prolonged and high-dosage use of stimulants, including ethylphenidate, can potentially lead to a stimulant-induced psychosis characterized by symptoms like paranoia, hallucinations, or delusions. A review on the treatment of amphetamine, dextroamphetamine, and methamphetamine abuse-induced psychosis suggests that about 5–15% of users do not fully recover from such episodes. The same review indicates that antipsychotic medications can effectively alleviate symptoms of acute amphetamine psychosis.

Dangerous Interactions:

Combining psychoactive substances can pose unforeseen dangers and even life-threatening risks. Some interactions that may be hazardous include:

- 25x-NBOMe & 25x-NBOH: Combinations with ethylphenidate should be strictly avoided due to the potential for excessive stimulation and heart strain, which can lead to increased blood pressure, vasoconstriction, panic attacks, thought loops, seizures, and in severe cases, heart failure.

- Alcohol: Combining alcohol with stimulants can be risky, as stimulants mask alcohol’s depressant effects. This can result in blackouts and severe respiratory depression when the stimulant’s effects wane. If combined, alcohol consumption should be strictly limited.

- DXM: Combinations with DXM should be avoided due to its inhibitory effects on serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake, which can increase the risk of panic attacks, hypertensive crisis, or serotonin syndrome when combined with serotonin releasers like MDMA.

- MDMA: Combining MDMA with other stimulants may exacerbate neurotoxic effects and pose risks to blood pressure and heart health.

- MXE: Reports suggest that combining MXE with ethylphenidate may elevate blood pressure dangerously and increase the risk of mania and psychosis.

- Dissociatives: Both classes carry risks of delusions, mania, and psychosis, which may be heightened when combined.

- Stimulants: Ethylphenidate can be hazardous when combined with other stimulants like cocaine, as they may excessively raise heart rate and blood pressure.

- Tramadol: Tramadol can lower the seizure threshold, and combining it with stimulants like ethylphenidate may further increase this risk.

- MAOIs: Combining ethylphenidate with MAOIs can raise neurotransmitter levels, including dopamine, to potentially dangerous or fatal levels.

- Cocaine: Combining ethylphenidate with cocaine may put excessive strain on the heart.

It is crucial to conduct independent research to ascertain the safety of combining multiple substances, as potential interactions can vary. Always prioritize safety and responsible usage practices.

Legal status

Ethylphenidate, while not subject to international control, remains readily accessible through online research chemical vendors. However, it is essential to note that its legal status varies across jurisdictions, with specific regulations in place in the following regions:

Australia: In Australia, both state and federal legislation encompass provisions that extend control to analogues of controlled substances. Ethylphenidate is considered an analogue of methylphenidate under this legislation.

Austria: As of January 1, 2012, Ethylphenidate is illegal to possess, produce, and sell in Austria under the Neue-Psychoaktive-Substanzen-Gesetz Österreich (New Psychoactive Substances Act).

Canada: Ethylphenidate was listed on Schedule III of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA) as of May 5, 2017.

Denmark: Ethylphenidate has been illegal in Denmark since February 1, 2013.

Germany: Ethylphenidate falls under Anlage II BtMG (Narcotics Act, Schedule II) in Germany, making it illegal to manufacture, possess, import, export, buy, sell, procure, or dispense without a license since July 17, 2013.

Jersey: Under the Misuse of Drugs (Jersey) Law 1978, Ethylphenidate is considered illegal in Jersey.

The Netherlands: Ethylphenidate was added to the Opiumwet (Opium Act) on Lijst I as of April 27, 2018, making it illegal in the Netherlands.

Sweden: Ethylphenidate has been illegal in Sweden since December 15, 2012.

Switzerland: Ethylphenidate is classified as a controlled substance and specifically named under Verzeichnis D in Switzerland.

United Kingdom: In the United Kingdom, Ethylphenidate was classified as a class B drug as of May 31, 2017, rendering it illegal to possess, produce, or supply.

United States: Ethylphenidate is not explicitly controlled at the federal level in the United States. However, it may potentially be regarded as an analog of a Schedule II substance (methylphenidate) under the Federal Analog Act.

FAQ

1. What is Ethylphenidate?

- Ethylphenidate is a synthetic stimulant compound belonging to the substituted phenethylamine and substituted phenidate classes. It shares structural similarities with methylphenidate, a medication for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

2. What are the Effects of Ethylphenidate?

- Ethylphenidate produces stimulating effects, including increased alertness, focus, and euphoria. It can also lead to physical effects like increased heart rate, appetite suppression, and stimulation.

3. Is Ethylphenidate Legal?

- The legal status of Ethylphenidate varies by country and region. It is illegal or subject to restrictions in some countries, while in others, it may remain unregulated or in a legal grey area. Always check your local laws and regulations before using Ethylphenidate.

4. How is Ethylphenidate Typically Used?

- Ethylphenidate is commonly insufflated (snorted) or taken orally. Some users may also administer it through other routes, but these methods are less common.

5. What Are the Potential Risks and Side Effects of Ethylphenidate?

- Ethylphenidate may carry risks such as addiction, cardiovascular strain, anxiety, and psychosis when used excessively or over an extended period. Users may also experience side effects like increased heart rate, dehydration, and appetite suppression.

6. Is Ethylphenidate Safe to Use?

- The safety of Ethylphenidate use is a topic of concern. Due to limited scientific research, it’s challenging to assess its long-term effects accurately. Safe use practices, harm reduction measures, and adherence to local laws are essential for minimizing risks.

7. Can Ethylphenidate Be Used Recreationally or for Research Purposes?

- Ethylphenidate has been used recreationally by some individuals, although its legal status and potential risks should be carefully considered. Initially marketed as a research chemical, but its availability has dwindled due to regulatory changes.

8. Is Ethylphenidate Addictive?

- Ethylphenidate has the potential for addiction, as it shares characteristics with other stimulants known to be habit-forming. Frequent and high-dosage use increases the risk of developing dependence.

9. Can Ethylphenidate Be Combined with Other Substances?

- Combining Ethylphenidate with other substances, including alcohol or other stimulants, can be dangerous and may lead to unforeseen health risks or interactions. Always exercise caution and consider potential interactions before combining substances.

10. Where Can I Find More Information About Ethylphenidate?

- It’s crucial to rely on reputable sources for information about Ethylphenidate. Consult scientific literature authoritative websites, or consult with healthcare professionals for accurate and up-to-date information. Additionally, always prioritize safety and responsible use when considering its consumption.

References

- Patrick, K. S., Williard, R. L., VanWert, A. L., Dowd, J. J., Oatis, J. E., Middaugh, L. D. (April 21, 2005). “The Synthesis and Pharmacology of Ethylphenidate Enantiomers: The Human Transesterification Metabolite of Methylphenidate and Ethanol.” Published in the Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 48(8), 2876–2881. DOI: 10.1021/jm0490989. ISSN 0022-2623.

- Williard, R. L., Middaugh, L. D., Zhu, H.-J. B., Patrick, K. S. (February 2007). “Methylphenidate and Its Ethanol Transesterification Metabolite Ethylphenidate: Brain Disposition, Monoamine Transporters, and Motor Activity.” Published in Behavioral Pharmacology, 18(1), 39–51. DOI: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3280143226. ISSN 0955-8810.

- Williard, R. L., Middaugh, L. D., Zhu, H.-J. B., Patrick, K. S. (February 2007). “Methylphenidate and Its Ethanol Transesterification Metabolite Ethylphenidate: Brain Disposition, Monoamine Transporters, and Motor Activity.” Published in Behavioral Pharmacology, 18(1), 39–51. DOI: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3280143226. ISSN 0955-8810.

- Markowitz, J. S., DeVane, C. L., Boulton, D. W., Nahas, Z., Risch, S. C., Diamond, F., Patrick, K. S. (June 2000). “Ethylphenidate Formation in Human Subjects after the Administration of a Single Dose of Methylphenidate and Ethanol.” Published in Drug Metabolism and Disposition: The Biological Fate of Chemicals, 28(6), 620–624. ISSN 0090-9556.

- Markowitz, J. S., Logan, B. K., Diamond, F., Patrick, K. S. (August 1999). “Detection of the Novel Metabolite Ethylphenidate after Methylphenidate Overdose with Alcohol Coingestion.” Published in the Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 19(4), 362–366. DOI: 10.1097/00004714-199908000-00013. ISSN 0271-0749.

- Bourland, J. A., Martin, D. K., Mayersohn, M. (December 1997). “Carboxylesterase-Mediated Transesterification of Meperidine (Demerol) and Methylphenidate (Ritalin) in the Presence of [2H6]Ethanol: Preliminary In Vitro Findings Using a Rat Liver Preparation.” Published in the Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 86(12), 1494–1496. DOI: 10.1021/js970072x. ISSN 0022-3549.

- Shoptaw, S. J., Kao, U., Ling, W. (January 21, 2009). “Treatment for Amphetamine Psychosis.” Published in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003026.pub3. ISSN 1465-1858.

- Hofmann, F. G. (1983). “A Handbook on Drug and Alcohol Abuse: The Biomedical Aspects” (2nd ed.). Published by Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195030563.

- Talaie, H.; Panahandeh, R.; Fayaznouri, M. R.; Asadi, Z.; Abdollahi, M. (2009). “Dose-Independent Occurrence of Seizure with Tramadol.” Published in the Journal of Medical Toxicology, 5(2), 63–67. DOI: 10.1007/BF03161089. ISSN 1556-9039. eISSN 1937-6995.

- Gillman, P. K. (2005). “Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors, Opioid Analgesics, and Serotonin Toxicity.” Published in the British Journal of Anaesthesia, 95(4), 434–441. DOI: 10.1093/bja/aei210. ISSN 0007-0912. eISSN 1471-6771. PMID 16051647.

- “Order Amending Schedule III to the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (Methylphenidate).” Published by Public Works and Government Services Canada. Archived from the original on June 13, 2017. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- “Anlage II BtMG” (in German). Published by Bundesministerium der Justiz und für Verbraucherschutz. Retrieved December 23, 2019.

- “Siebenundzwanzigste Verordnung zur Änderung betäubungsmittelrechtlicher Vorschriften” (in German). Published by Bundesanzeiger Verlag. Retrieved December 23, 2019.

- “§ 29 BtMG” (in German). Published by Bundesministerium der Justiz und für Verbraucherschutz. Retrieved December 23, 2019.

- “Misuse of Drugs (General Provisions) Order 2009” (Revised Edition) (in English). Published by Jersey Law. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- “Opiumwet” (in Dutch). Published by Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- “Forordning 1992:1554 om kontroll av narkotika” (in Swedish). Published by Riksdagen. Retrieved 1992:1554.

- “Verordnung des EDI über die Verzeichnisse der Betäubungsmittel, psychotropen Stoffe, Vorläuferstoffe und Hilfschemikalien” (in German). Published by Bundeskanzlei [Federal Chancellery of Switzerland]. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- “The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (Amendment) Order 2017” (in English).