Beautiful Plants For Your Interior

Sumamry

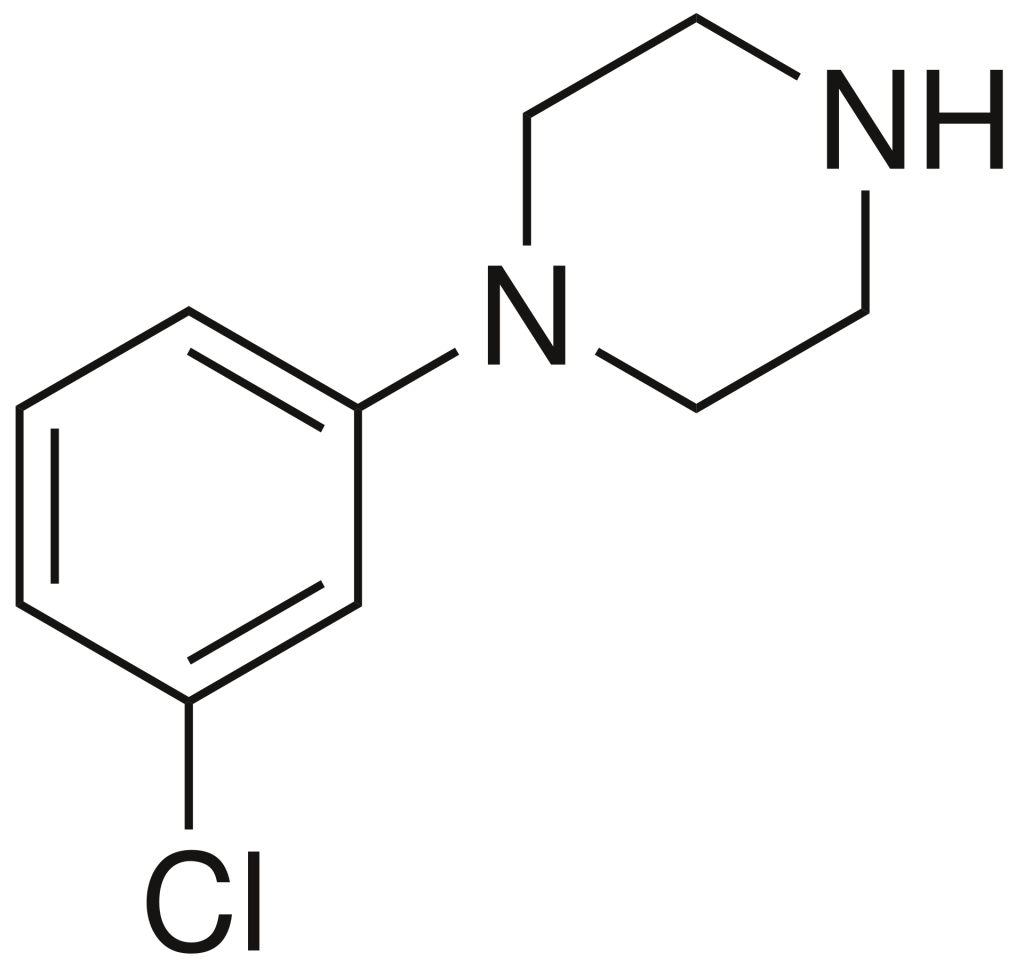

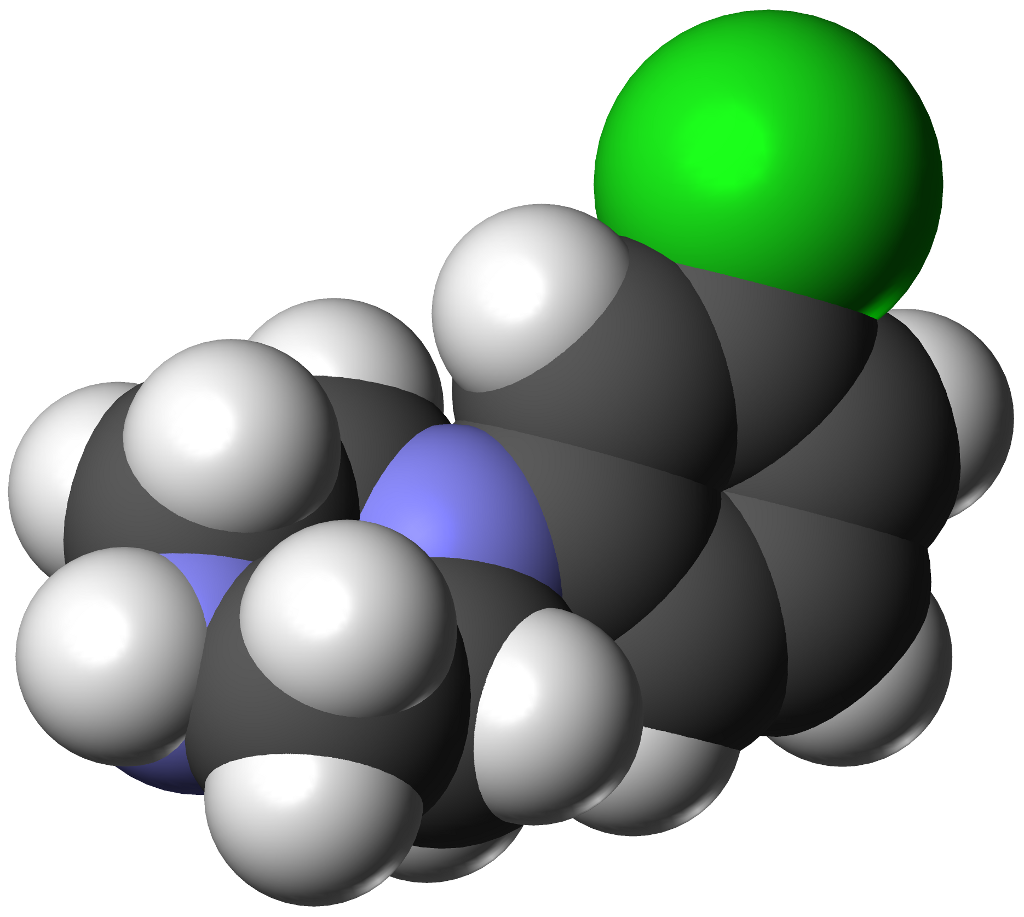

meta-Chlorophenylpiperazine (mCPP) belongs to the phenylpiperazine class of psychoactive drugs. Originally developed for scientific research purposes in the late 1970s, it later found its way into the designer drug market in the mid-2000s. Notably, mCPP has been identified in pills marketed as legal alternatives to illicit stimulants in New Zealand, and it has also been detected in pills sold as “ecstasy” in Europe and the United States.

Despite being marketed as a recreational substance, mCPP is widely recognized as an unpleasant experience and generally undesirable among drug users. It lacks reinforcing effects but is associated with psychostimulant, anxiety-inducing, and hallucinogenic effects. Additionally, it is known to induce dysphoria, depression, and anxiety in both rodents and humans. For individuals susceptible to panic attacks, mCPP has been reported to trigger such episodes. Moreover, it exacerbates symptoms in individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Notably, mCPP has a reputation for causing headaches in humans and has been employed in the testing of potential antimigraine medications. Furthermore, due to its potent anorectic (appetite-suppressing) effects, it has spurred the development of selective 5-HT2C receptor agonists as potential treatments for obesity.

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name | |

| CAS Number | 6640-24-0 |

|---|---|

| PubChem CID | 1355 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 142 |

| ChemSpider | 1314 |

| UNII | REY0CNO998 |

| KEGG | C11738 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:10588 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL478 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID9045138 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.026.959 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C10H13ClN2 |

| Molar mass | 196.68 g·mol−1 |

Pharmacology

mCPP exhibits notable affinity for various serotonin receptors, including 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT1D, 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, 5-HT2C, 5-HT3, and 5-HT7 receptors, in addition to the serotonin transporter (SERT). It also displays some affinity for α1-adrenergic, α2-adrenergic, H1, I1, and NET receptors. mCPP predominantly acts as an agonist at most serotonin receptors. Remarkably, it functions both as a serotonin reuptake inhibitor and a serotonin-releasing agent.

The most pronounced effects of mCPP are observed at the 5-HT2B and 5-HT2C receptors. Its discriminative cue is primarily mediated through the 5-HT2C receptor. Undesirable effects associated with mCPP, such as anxiety, headaches, and reduced appetite, are likely attributed to its actions on the 5-HT2C receptor. Additionally, mCPP can induce nausea, decreased activity, and penile erections, with the latter two effects resulting from increased 5-HT2C activity and the former likely due to 5-HT3 receptor stimulation.

In comparative studies, mCPP displays approximately 10-fold selectivity for the human 5-HT2C receptor over the human 5-HT2A and 5-HT2B receptors (with Ki values of 3.4 nM, 32.1 nM, and 28.8 nM, respectively). It acts as a partial agonist of human 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors but functions as an antagonist of the human 5-HT2B receptors.

Pharmacokinetics:

mCPP undergoes metabolism primarily through the CYP2D6 isoenzyme, involving hydroxylation to form para-hydroxy-mCPP (p-OH-mCPP), which plays a significant role in its metabolism. The elimination half-life of mCPP falls within the range of 4 to 14 hours.

mCPP is a metabolite of various other piperazine-based drugs, including trazodone, nefazodone, etoperidone, enpiprazole, mepiprazole, cloperidone, peraclopone, and BRL-15,572. This metabolite is formed via dealkylation facilitated by the CYP3A4 enzyme. It is essential to exercise caution when administering drugs that produce mCPP as a metabolite concurrently with CYP2D6 inhibitors like bupropion, fluoxetine, paroxetine, and thioridazine, as these combinations are known to elevate concentrations of both the parent compound (e.g., trazodone) and mCPP.

Society and culture

- Belgium: mCPP is illegal in Belgium.

- Brazil: mCPP is illegal in Brazil.

- Canada: mCPP is not a controlled drug in Canada.

- China: As of October 2015, mCPP is a controlled substance in China.

- Czech Republic: mCPP is legal in the Czech Republic.

- Denmark: mCPP is illegal in Denmark.

- Finland: mCPP is illegal in Finland.

- Germany: mCPP is illegal in Germany.

- Hungary: mCPP has been illegal in Hungary since 2012.

- Japan: mCPP has been illegal in Japan since 2006.

- Netherlands: mCPP is legal in the Netherlands.

- New Zealand: Following the recommendation of the EACD, the New Zealand government passed legislation that placed BZP, as well as other piperazine derivatives (TFMPP, mCPP, pFPP, MeOPP, and MBZP), into Class C of the New Zealand Misuse of Drugs Act 1975. Although the ban was initially intended to take effect on December 18, 2007, the law change was enacted the following year. Consequently, the sale of BZP and the other listed piperazines became illegal in New Zealand as of April 1, 2008. An amnesty for possession and usage of these drugs remained in place until October 2008, after which they became entirely illegal. However, it is essential to note that mCPP is legally available for scientific research.

- Norway: mCPP is illegal in Norway.

- Russia: mCPP is illegal in Russia.

- Sweden: mCPP is illegal in Sweden.

- Poland: mCPP is illegal in Poland.

- United States: mCPP is not classified at the federal level in the United States. However, it could be considered a controlled substance analogue of BZP, and as such, its purchase, sale, or possession may be subject to prosecution under the Federal Analog Act. Notably, “chlorophenylpiperazine” is classified as a Schedule I controlled substance in the state of Florida, making it illegal to buy, sell, or possess within the state.

- Turkey: mCPP has been illegal in Turkey since May 20, 2009.

FAQ

1. What is mCPP (meta-chlorophenylpiperazine)?

mCPP is a psychoactive drug belonging to the phenylpiperazine class. It was initially developed for scientific research but later found its way into recreational use.

2. What effects does mCPP produce?

mCPP is known for its psychostimulant, anxiety-provoking, and hallucinogenic effects. It also induces headaches and nausea. Although it has been marketed as a recreational substance, it is generally considered an unpleasant experience by users.

3. What is mCPP’s mechanism of action?

mCPP primarily affects various serotonin receptors, including 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT1D, 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, 5-HT2C, 5-HT3, and 5-HT7 receptors, as well as the serotonin transporter (SERT). It acts as an agonist at most serotonin receptors.

4. How is mCPP metabolized?

mCPP is metabolized through the CYP2D6 isoenzyme, primarily by hydroxylation to para-hydroxy-mCPP (p-OH-mCPP). This metabolite plays a significant role in its metabolism. The elimination half-life of mCPP is 4 to 14 hours.

5. Is mCPP legal in my country?

The legal status of mCPP varies by country. It is essential to check your local laws. In some countries, such as Belgium, Brazil, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Hungary, Japan, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and Poland, mCPP is illegal. In contrast, it is legal in the Netherlands for scientific research purposes.

6. Is mCPP legal in the United States?

At the federal level in the United States, mCPP is not scheduled. However, it could be considered a controlled substance analogue of BZP, which might result in prosecution under the Federal Analog Act. Furthermore, in the state of Florida, “chlorophenylpiperazine” is a Schedule I controlled substance, making it illegal.

7. Is mCPP available for scientific research?

Yes, in some places like the Netherlands and New Zealand, mCPP is legally used for scientific research.

8. What are the side effects of mCPP?

Common side effects of mCPP use include anxiety, headaches, appetite loss, nausea, and hallucinogenic effects. It has also been known to induce panic attacks in susceptible individuals and worsen obsessive–compulsive symptoms.

9. What is the history of mCPP?

mCPP was developed for scientific research in the late 1970s but later became available as a designer drug for recreational use in the mid-2000s. It has been marketed as a legal alternative to illicit stimulants.

10. Does mCPP have any medical applications?

mCPP has been used in testing potential antimigraine medications due to its ability to induce headaches in humans. Additionally, its potent anorectic effects have led to research into selective 5-HT2C receptor agonists for the treatment of obesity.

References

**1. Anvisa (2023-07-24). “RDC Nº 804 – Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial” [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 804 – Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 2023-07-25). Archived from the original on 2023-08-27. Retrieved 2023-08-27.

**2. Rotzinger S, Bourin M, Akimoto Y, Coutts RT, Baker GB (August 1999). “Metabolism of some “second”- and “fourth”-generation antidepressants: iprindole, viloxazine, bupropion, mianserin, maprotiline, trazodone, nefazodone, and venlafaxine”. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 19 (4): 427–42. doi:10.1023/a:1006953923305. PMID 10379419. S2CID 19585113.

**3. Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB (2017). The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychopharmacology, Fifth Edition. American Psychiatric Pub. pp. 460–. ISBN 978-1-58562-523-9.

**4. Bossong MG, Van Dijk JP, Niesink RJ (December 2005). “Methylone and mCPP, two new drugs of abuse?”. Addiction Biology. 10 (4): 321–3. doi:10.1080/13556210500350794. PMID 16318952. S2CID 36169592. Archived from the original on 2013-01-05.

**5. Lecompte Y, Evrard I, Arditti J (2006). “[Metachlorophenylpiperazine (mCPP): a new designer drug]”. Thérapie (in French). 61 (6): 523–30. doi:10.2515/therapie:2006093. PMID 17348609.

**6. Bossong M, Brunt T, Van Dijk J, et al. (March 2009). “mCPP: an undesired addition to the ecstasy market”. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 24 (9): 1395–401. doi:10.1177/0269881109102541. PMID 19304863. S2CID 11186375.

**7. Vogels N, Brunt TM, Rigter S, van Dijk P, Vervaeke H, Niesink RJ (December 2009). “Content of ecstasy in the Netherlands: 1993-2008”. Addiction. 104 (12): 2057–66. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02707.x. PMID 19804461.

**8. World Health Organization. “1-(3-chlorophenyl) piperazine (mCPP) – Expert peer review on pre-review report” (PDF). Retrieved 2021-01-12.

**9. Tancer ME, Johanson CE (December 2001). “The subjective effects of MDMA and mCPP in moderate MDMA users”. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 65 (1): 97–101. doi:10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00146-6. PMID 11714594.

**10. Tancer M, Johanson CE (October 2003). “Reinforcing, subjective, and physiological effects of MDMA in humans: a comparison with d-amphetamine and mCPP”. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 72 (1): 33–44. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(03)00172-8. PMID 14563541.

**11. Nelson DL, Lucaites VL, Wainscott DB, Glennon RA (January 1999). “Comparisons of hallucinogenic phenylisopropylamine binding affinities at cloned human 5-HT2A, -HT(2B) and 5-HT2C receptors”. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology. 359 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1007/pl00005315. PMID 9933142. S2CID 20150858.

**12. Rajkumar R, Pandey DK, Mahesh R, Radha R (April 2009). “1-(m-Chlorophenyl)piperazine induces depressogenic-like behaviour in rodents by stimulating the neuronal 5-HT(2A) receptors: proposal of a modified rodent antidepressant assay”. European Journal of Pharmacology. 608 (1–3): 32–41. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.02.041. PMID 19269287.

**13. Kennett GA, Whitton P, Shah K, Curzon G (May 1989). “Anxiogenic-like effects of mCPP and TFMPP in animal models are opposed by 5-HT1C receptor antagonists”. European Journal of Pharmacology. 164 (3): 445–454. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(89)90252-5. PMID 2767117.

**14. Klein E, Zohar J, Geraci MF, Murphy DL, Uhde TW (November 1991). “Anxiogenic effects of m-CPP in patients with panic disorder: comparison to caffeine’s anxiogenic effects”. Biological Psychiatry. 30 (10): 973–984. doi:10.1016/0006-3223(91)90119-7. PMID 1756202. S2CID 43010184.

**15. Charney DS, Woods SW, Goodman WK, Heninger GR (1987). “Serotonin function in anxiety. II. Effects of the serotonin agonist MCPP in panic disorder patients and healthy subjects”. Psychopharmacology. 92 (1): 14–24. doi:10.1007/bf00215473. PMID 3110824. S2CID 43079787.

**16. Van Veen JF, Van der Wee NJ, Fiselier J, Van Vliet IM, Westenberg HG (October 2007). “Behavioural effects of rapid intravenous administration of meta-chlorophenylpiperazine (m-CPP) in patients with generalized social anxiety disorder, panic disorder and healthy controls”. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 17 (10): 637–642. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.03.005. PMID 17481859. S2CID 41601926.

**17. van der Wee NJ, Fiselier J, van Megen HJ, Westenberg HG (October 2004). “Behavioural effects of rapid intravenous administration of meta-chlorophenylpiperazine in patients with panic disorder and controls”. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 14 (5): 413–417. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2004.01.001. PMID 15336303. S2CID 28987431.

**18. Hollander E, DeCaria CM, Nitescu A, Gully R, Suckow RF, Cooper TB, et al. (January 1992). “Serotonergic function in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behavioral and neuroendocrine responses to oral m-chlorophenylpiperazine and fenfluramine in patients and healthy volunteers”. Archives of General Psychiatry. 49 (1): 21–28. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820010021003. PMID 1728249.

**19. Broocks A, Pigott TA, Hill JL, Canter S, Grady TA, L’Heureux F, Murphy DL (June 1998). “Acute intravenous administration of ondansetron and m-CPP, alone and in combination, in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD): behavioral and biological results”. Psychiatry Research. 79 (1): 11–20. doi:10.1016/S0165-1781(98)00029-8. PMID 9676822. S2CID 30339598.

**20. Pigott TA, Zohar J, Hill JL, Bernstein SE, Grover GN, Zohar-Kadouch RC, Murphy DL (March 1991). “Metergoline blocks the behavioral and neuroendocrine effects of orally administered m-chlorophenylpiperazine in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder”. Biological Psychiatry. 29 (5): 418–426. doi:10.1016/0006-3223(91)90264-M. PMID 2018816. S2CID 37648659.

**21. Leone M, Attanasio A, Croci D, Filippini G, D’Amico D, Grazzi L, et al. (July 2000). “The serotonergic agent m-chlorophenylpiperazine induces migraine attacks: A controlled study”. Neurology. 55 (1): 136–139. doi:10.1212/wnl.55.1.136. PMID 10891925. S2CID 27617431.

**22. Martin RS, Martin GR (February 2001). “Investigations into migraine pathogenesis: time course for effects of m-CPP, BW723C86 or glyceryl trinitrate on appearance of Fos-like immunoreactivity in rat trigeminal nucleus caudalis (TNC)”. Cephalalgia. 21 (1): 46–52. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.2001.00157.x. PMID 11298663. S2CID 8471836.

**23. Petkov VD, Belcheva S, Konstantinova E (December 1995). “Anxiolytic effects of dotarizine, a possible antimigraine drug”. Methods and Findings in Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology. 17 (10): 659–668. PMID 9053586.

**24. Kennett GA, Curzon G (1988). “Evidence that hypophagia induced by mCPP and TFMPP requires 5-HT1C and 5-HT1B receptors; hypophagia induced by RU 24969 only requires 5-HT1B receptors”. Psychopharmacology. 96 (1): 93–100. doi:10.1007/BF02431539. PMID 2906446. S2CID 21417374.

**25. Sargent PA, Sharpley AL, Williams C, Goodall EM, Cowen PJ (October 1997). “5-HT2C receptor activation decreases appetite and body weight in obese subjects”. Psychopharmacology. 133 (3): 309–312. doi:10.1007/s002130050407. PMID 9361339. S2CID 7125577.

**26. Hayashi A, Suzuki M, Sasamata M, Miyata K (March 2005). “Agonist diversity in 5-HT(2C) receptor-mediated weight control in rats”. Psychopharmacology. 178 (2–3): 241–249. doi:10.1007/s00213-004-2019-z. PMID 15719229. S2CID 7580231.

**27. Halford JC, Harrold JA, Boyland EJ, Lawton CL, Blundell JE (2007). “Serotonergic drugs : effects on appetite expression and use for the treatment of obesity”. Drugs. 67 (1): 27–55. doi:10.2165/00003495-200767010-00004. PMID 17209663. S2CID 46972692.

**28. Roth, BL; Driscol, J. “PDSP Ki Database”. Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

**29. Owens MJ, Morgan WN, Plott SJ, Nemeroff CB (1997). “Neurotransmitter receptor and transporter binding profile of antidepressants and their metabolites”. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 283 (3): 1305–22. PMID 9400006.

**30. Hamik A, Peroutka SJ (1989). “1-(m-chlorophenyl)piperazine (mCPP) interactions with neurotransmitter receptors in the human brain”. Biol. Psychiatry. 25 (5): 569–75. doi:10.1016/0006-3223(89)90217-5. PMID 2537663. S2CID 46730665.

**31. Boess FG, Martin IL (1994). “Molecular biology of 5-HT receptors”. Neuropharmacology. 33 (3–4): 275–317. doi:10.1016/0028-3908(94)90059-0. PMID 7984267. S2CID 35553281.

**32. Hamblin MW, Metcalf MA (1991). “Primary structure and functional characterization of a human 5-HT1D-type serotonin receptor”. Mol. Pharmacol. 40 (2): 143–8. PMID 1652050.

**33. Bonhaus DW, Bach C, DeSouza A, Salazar FH, Matsuoka BD, Zuppan P, Chan HW, Eglen RM (1995). “The pharmacology and distribution of human 5-hydroxytryptamine2B (5-HT2B) receptor gene products: comparison with 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors”. Br. J. Pharmacol. 115 (4): 622–8. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb14977.x. PMC 1908489. PMID 7582481.

**34. Rothman RB, Baumann MH, Savage JE, Rauser L, McBride A, Hufeisen SJ, Roth BL (2000). “Evidence for possible involvement of 5-HT(2B) receptors in the cardiac valvulopathy associated with fenfluramine and other serotonergic medications”. Circulation. 102 (23): 2836–41. doi:10.1161/01.cir.102.23.2836. PMID 11104741.

**35. Porter RH, Benwell KR, Lamb H, Malcolm CS, Allen NH, Revell DF, Adams DR, Sheardown MJ (1999). “Functional characterization of agonists at recombinant human 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B and 5-HT2C receptors in CHO-K1 cells”. Br. J. Pharmacol. 128 (1): 13–20. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0702751. PMC 1571597. PMID 10498829.

**36. Bentley JM, Adams DR, Bebbington D, Benwell KR, Bickerdike MJ, Davidson JE, Dawson CE, Dourish CT, Duncton MA, Gaur S, George AR, Giles PR, Hamlyn RJ, Kennett GA, Knight AR, Malcolm CS, Mansell HL, Misra A, Monck NJ, Pratt RM, Quirk K, Roffey JR, Vickers SP, Cliffe IA (2004). “Indoline derivatives as 5-HT(2C) receptor agonists”. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 14 (9): 2367–70. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.05.001. PMID 15081042.

**37. Silverstone PH, Rue JE, Franklin M, et al. (September 1994). “The effects of administration of mCPP on psychological, cognitive, cardiovascular, hormonal and MHPG measurements in human volunteers”. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 9 (3): 173–8. doi:10.1097/00004850-199409000-00005. PMID 7814826. S2CID 25464507.

**38. Samanin R, Mennini T, Ferraris A, Bendotti C, Borsini F, Garattini S (August 1979). “Chlorophenylpiperazine: a central serotonin agonist causing powerful anorexia in rats”. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology. 308 (2): 159–63. doi:10.1007/BF00499059. PMID 503247. S2CID 19293115.

**39. Odagaki Y, Toyoshima R, Yamauchi T (May 2005). “Trazodone and its active metabolite m-chlorophenylpiperazine as partial agonists at 5-HT1A receptors assessed by [35S]GTPgammaS binding”. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 19 (3): 235–41. doi:10.1177/0269881105051526. PMID 15888508. S2CID 27389008.

**40. Pettibone DJ, Williams M (May 1984). “Serotonin-releasing effects of substituted piperazines in vitro”. Biochemical Pharmacology. 33 (9): 1531–5. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(84)90424-6. PMID 6610423.