- 1 MDMA: Forms, Effects, and Online Purchasing Options

- 2 Where to Buy MDMA Online

- 3 Understanding Different Forms of MDMA

- 4 Effects and Appeal of Molly

- 5 Tips for Buying MDMA

- 6 Final Thoughts

- 7 Summary

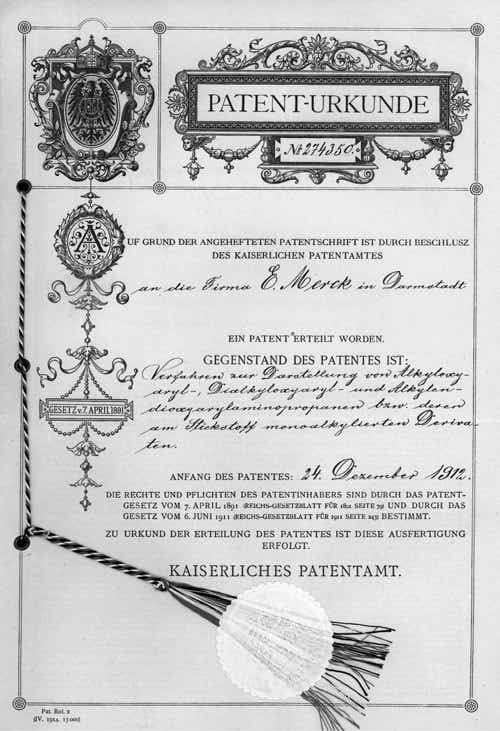

- 8 History and culture

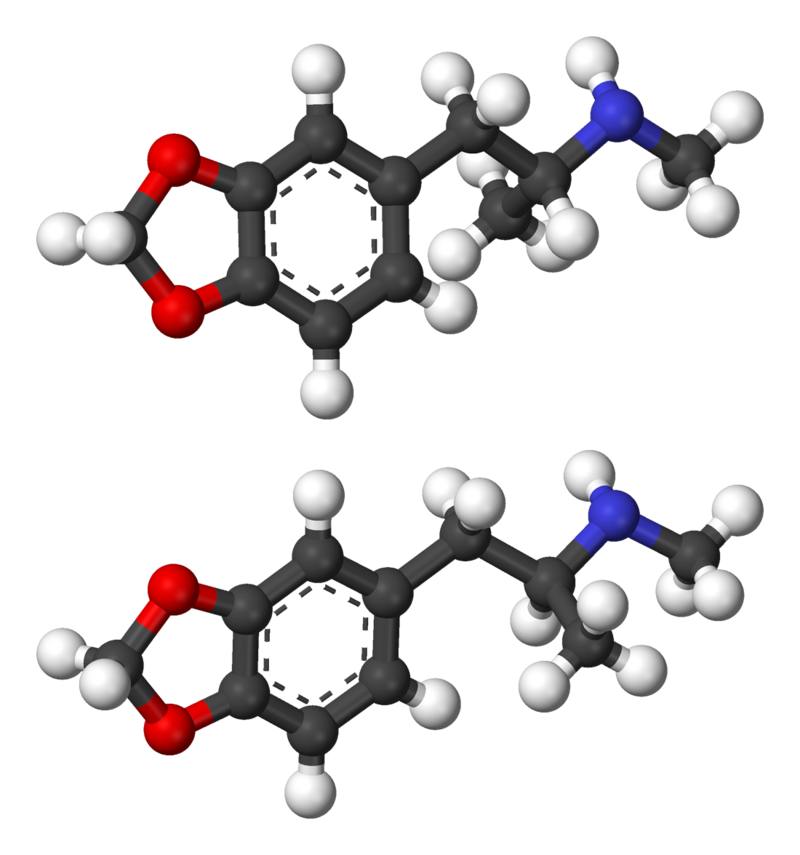

- 9 Chemistry

- 10 Pharmacology

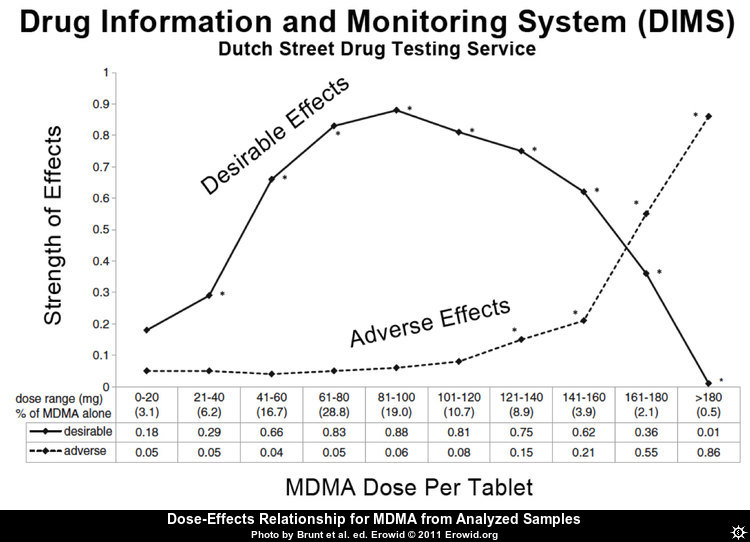

- 11 Dosage

- 12 Subjective effects

- 13 Names and forms

- 14 Research

- 15 Reagent results

- 16 Toxicity

- 16.1 Water Intoxication and Electrolyte Imbalance:

- 16.2 Preventing Water Intoxication and Electrolyte Imbalance:

- 16.3 Neurotoxicity:

- 16.4 Retracted Article on Dopaminergic Neurotoxicity:

- 16.5 Cardiotoxicity:

- 16.6 Dependence and Abuse Potential:

- 16.7 Dangerous Interactions:

- 16.8 Serotonin Syndrome Risk:

- 17 Legal status

- 18 FAQ

- 18.1 1. What is MDMA?

- 18.2 2. How is MDMA typically consumed?

- 18.3 3. What are the effects of MDMA?

- 18.4 4. Is MDMA legal?

- 18.5 5. Are there any medical uses for MDMA?

- 18.6 6. What are the short-term risks of MDMA use?

- 18.7 7. Can MDMA be addictive?

- 18.8 8. What are the long-term effects of MDMA use?

- 18.9 9. Are there dangerous drug interactions with MDMA?

- 18.10 10. How can I reduce the risks associated with MDMA use?

- 18.11 11. Is it safe to use MDMA recreationally?

- 18.12 12. Where can I find help for MDMA-related issues?

- 19 References

MDMA: Forms, Effects, and Online Purchasing Options

MDMA, often referred to as “molly” or “ecstasy,” has remained a popular choice for those seeking enhanced social experiences and heightened sensory effects. With forms ranging from crystalline powder to pills, finding MDMA products that meet your needs has never been more accessible.

Where to Buy MDMA Online

Navigating the modern market for MDMA is increasingly digital. Trusted platforms offering MDMA for sale online provide a range of options, from party-ready extasy drugs to specialized research chemicals. Whether you’re looking to buy MDMA powder or explore molly drug effects, reputable vendors prioritize product quality and discreet delivery.

When conducting an MDMA online purchase, look for suppliers who detail their offerings, ensuring clarity around options like MDMA in crystal form or powdered variants. For those exploring topics like “where can I buy molly” or “buy mdma online,” secure platforms with positive reviews are a smart starting point.

Understanding Different Forms of MDMA

MDMA is available in several popular formats to suit various preferences:

- Crystallized MDMA: Featuring visible crystals, this is one of the purest forms of MDMA available. Perfect for experienced users or those seeking concentrated effects.

- Molly Crystals: Known for their rock-like appearance, molly crystals offer a potent and aesthetically appealing option.

- Molly Powder: Easier to measure, this variant is ideal for precise usage and blends seamlessly into social settings.

- Drugs Pills and XTC Drugs: Traditional ecstasy pills often combine MDMA with other substances for varied experiences.

With terms like “molly crystal form” or “buy mdma canada,” users can find the style that best matches their preferences while exploring a wide range of options online.

Effects and Appeal of Molly

Dubbed as one of the best “love drugs,” MDMA is known for its ability to enhance emotional connection and empathy. It’s a popular choice at parties and festivals, appealing to individuals seeking heightened tactile sensations and engaging social interactions.

Molly in crystal form provides a more intense experience, while powdered MDMA allows users to control dosages. This versatility attracts those searching for the best combination of intensity, safety, and recoverability. Whether it’s enjoying the effects of molly drugs in rock form or testing black molly drugs, MDMA remains a staple for unforgettable moments.

Tips for Buying MDMA

For those considering purchasing MDMA for sale online, here are a few tips to ensure you’re making informed decisions:

- Check Vendor Reputation: Always choose suppliers with verified reviews and clear product descriptions.

- Select Your Form: From crystalized MDMA to mdma powder, ensure the format matches your intended use.

- Confirm Discreet Shipping: Look for vendors offering secure and anonymous delivery, especially when buying internationally in markets like the USA or UK.

For individuals researching “mdma buy” or “order mdma online,” weighing these factors will help you make safe, reliable choices.

Final Thoughts

Whether you’re exploring molly drug effects or simply searching for “where can I buy ecstasy,” MDMA’s appeal lies in its versatility and social enhancements. From powder MDMA to crystallized molly variants, the right product can elevate any experience. Take time to research, confirm product purity, and choose trusted sellers for a secure and satisfying purchase.

Summary

3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine, commonly known as MDMA or by various street names like ecstasy, E, XTC, Emma, molly, mandy, and pingers, belongs to the entactogen class within the amphetamine category. It is the most recognized and widely utilized entactogen, encompassing other compounds such as MDA, methylone, 4-MMC, and 6-APB. Its mode of action primarily involves the stimulation of serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine release within the brain.

Initially synthesized in 1912 by the pharmaceutical firm Merck, MDMA’s actual human use didn’t surface until the 1970s when it became recognized within underground psychotherapeutic circles in the United States. During the early 1980s, it transitioned into the realm of nightlife and rave culture, eventually becoming a controlled substance in 1985. By 2014, MDMA had gained a reputation as one of the most prevalent recreational drugs worldwide, ranking alongside cocaine and cannabis.

In contemporary times, recreational MDMA consumption is strongly associated with dance parties, electronic dance music events, and the club and rave scenes. Ongoing research endeavours are exploring the potential therapeutic applications of MDMA in addressing treatment-resistant post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), social anxiety among autistic adults, and anxiety associated with life-threatening illnesses.

Subjectively, MDMA induces a range of effects, including heightened stimulation, anxiety alleviation, reduced inhibitions, enhanced empathy and sociability, relaxation, and profound euphoria. It garners its entactogenic classification due to its ability to promote feelings of emotional closeness both with oneself and others. An essential aspect of MDMA is its rapid development of tolerance, with many users reporting a significant loss of effectiveness when used frequently.

To minimize potential harm, it is strongly recommended to allow one to three months between MDMA use to permit the brain sufficient time for serotonin levels to recover and to avert potential toxicity. Furthermore, excessive dosing and repeated redosing are discouraged, as it is believed to elevate the risk of harm associated with MDMA substantially.

MDMA carries a moderate to high potential for abuse and can lead to psychological dependence in some individuals. Acute adverse effects are often linked to high doses or multiple administrations, though susceptibility can result in single-dose toxicity. The most severe short-term health risks associated with MDMA encompass overheating and dehydration, which have tragically led to fatalities. It has also exhibited neurotoxic properties at elevated doses, although the extent of this risk in typical recreational usage remains uncertain. MDMA may induce excessive thirst and hinder urination, potentially leading to water intoxication and electrolyte imbalances. Additionally, it has been associated with sexual dysfunction, including erectile issues and delayed orgasms.

Practising harm reduction strategies is highly recommended for those considering MDMA use to mitigate potential risks associated with its consumption.

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| show IUPAC name | |

| CAS Number | 42542-10-9 [TOXNET] |

| PubChem CID | 1615 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 4574 |

| DrugBank | DB01454 |

| ChemSpider | 1556 |

| UNII | KE1SEN21RM |

| KEGG | D11172 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:1391 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL43048 |

| PDB ligand | B41 (PDBe, RCSB PDB) |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID90860791 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C11H15NO2 |

| Molar mass | 193.246 g·mol−1 |

History and culture

MDMA’s origin traces back to 1912 when the German chemist Dr. Anton Köllisch synthesized it during his tenure at Merck’s pharmaceutical firm. His primary objective was to develop substances for managing excessive bleeding, and MDMA entered the picture as an intermediate in the creation of methylhydrastinin, a methylated derivative of the hemostatic agent hydrastinine. At that point, there were no indications of MDMA being considered for its independent properties or effects.

The compound remained relatively obscure until 1927, when Dr. Max Oberlin conducted the first established pharmacological tests at Merck. He aimed to identify compounds with action profiles akin to adrenaline or ephedrine. Although the results held promise, research was halted due to escalating costs associated with MDMA’s production.

In 1965, American chemist Alexander Shulgin synthesized MDMA as an academic endeavour without exploring its psychoactive potential. It wasn’t until 1967, when Shulgin learned of MDMA’s effects from a student, he decided to experiment with it personally. Impressed by its effects, he believed in its therapeutic potential and introduced it to therapists and psychiatrists, eventually adopting it as an adjunct treatment for various psychological disorders.

During this period, psychotherapist Dr. Leo Zeff, who had come out of retirement, introduced the then-legal MDMA to more than 4,000 patients. From the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s, this period witnessed a surge in clinicians utilizing MDMA, referred to as “Adam” at the time, primarily in California.

Simultaneously, recreational use of MDMA gained popularity, especially in nightclub scenes, eventually drawing the attention of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). Following multiple hearings, a US Federal Administrative Law Judge recommended that MDMA be categorized as a Schedule III controlled substance, potentially allowing its medical use. However, the DEA’s director overturned this recommendation, classifying MDMA as a Schedule I controlled substance instead

In the United Kingdom, the 1971 Misuse of Drugs Act, initially modified in 1977 to encompass all ring-substituted amphetamines, including MDMA, was further amended in 1985 to include Ecstasy, classifying it under the Class A category.

Chemistry

MDMA, also known as 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine, is a synthetic compound in the substituted amphetamine class. Within the amphetamine class, these molecules share a standard phenethylamine core structure, consisting of a phenyl ring connected to an amino (NH2) group through an ethyl chain, with an additional methyl substitution at the Rα position. MDMA features a methyl substitution at the RN position, a characteristic it shares with methamphetamine.

Furthermore, a critical distinguishing feature of the MDMA molecule is the presence of oxygen substitutions at the R3 and R4 positions of the phenyl ring. These oxygen groups are integrated into a methylenedioxy ring through a methylene bridge. This unique methylenedioxy ring is a shared structural element with other substances classified as entactogens and stimulants, such as MDA, MDEA, and MDAI.

Pharmacology

MDMA primarily functions as a substance that induces the release of the three principal monoamine neurotransmitters: serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. Its interaction with trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) and vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) achieves this effect.

MDMA acts as a substrate for monoamine transporters, specifically those responsible for dopamine (DAT), norepinephrine (NET), and serotonin (SERT). This property allows MDMA to enter monoaminergic neurons through these neuronal membrane transport proteins. By serving as a monoamine transporter substrate, MDMA competitively inhibits these transporters’ reuptake of endogenous monoamines.

Furthermore, MDMA inhibits vesicular monoamine transporters (VMATs), with VMAT2 being highly expressed in the vesicular membranes of monoamine neurons. Once inside a monoamine neuron, MDMA acts as a VMAT2 inhibitor and a TAAR1 agonist. Inhibiting VMAT2 leads to increased concentrations of monoamine neurotransmitters in the neuron’s cytosol. The activation of TAAR1 by MDMA triggers protein kinase signalling events, which then phosphorylate the associated monoamine transporters in the neuron.

As a result of this phosphorylation, the monoamine transporters can either reverse their transport direction, moving neurotransmitters from inside the neuron to the synaptic cleft or withdrawing into the neuron. These actions result in an influx of neurotransmitters and noncompetitive reuptake inhibition at the neuronal membrane transporters. MDMA exhibits a much higher affinity for serotonin transporters than dopamine and norepinephrine transporters, leading to predominantly serotonergic effects.

MDMA also possesses weak agonist activity at postsynaptic serotonin receptors, specifically 5-HT1 and 5-HT2 receptors, with its metabolite MDA likely enhancing this effect. MDMA also influences cortisol, prolactin, and oxytocin levels in serum.

Moreover, MDMA acts as a ligand in both sigma receptor subtypes, although the specific roles and efficacies of these interactions are still not fully understood.

Dosage

| Dosage | |

|---|---|

| Threshold | 20 mg |

| Light | 20 – 80 mg |

| Common | 80 – 120 mg |

| Strong | 120 – 150 mg |

| Heavy | 150 mg + |

| Duration | |

| Total | 3 – 6 hours |

| Onset | 30 – 45 minutes |

| Come up | 15 – 30 minutes |

| Peak | 1.5 – 2.5 hours |

| Offset | 1 – 1.5 hours |

| After effects | 12 – 48 hours |

Subjective effects

Disclaimer: The effects described below are based on the Subjective Effect Index (SEI), which relies on anecdotal user reports and personal analyses from contributors to PsychonautWiki’s open research literature. Consequently, these effects should be approached with a critical mindset.

It’s essential to recognize that these effects may manifest differently or consistently, although higher doses are more likely to encompass the entire range of products. Additionally, it’s crucial to know that higher doses increase the risk of adverse effects, including addiction, severe injury, or even death ☠.

Physical:

- Abnormal heartbeat (requires citation)

- Appetite suppression

- Enhanced bodily control

- Bronchodilation (requires citation)

- Dehydration: Avoid excessive water intake; refer to the water intoxication and electrolyte imbalance section.

- Difficulty urinating: Caution against excessive water consumption; see the water intoxication and electrolyte imbalance section.

- Dry mouth: Caution against excessive water consumption; see the water intoxication and electrolyte imbalance section.

- Excessive yawning: Often linked to serotonergic activity, more familiar with higher doses or pure MDMA, sometimes used as a quality indicator.

- Increased blood pressure

- Elevated bodily temperature: MDMA’s serotonin-releasing property results in a rise in core body temperature, which can be dangerous in scorching environments, potentially leading to serotonin toxicity. Avoid excessive water intake; refer to the water intoxication and electrolyte imbalance section.

- Increased heart rate

- Increased perspiration: Caution against excessive water intake; see the water intoxication and electrolyte imbalance section.

- Muscle contractions

- Nausea: More prevalent during the initial phase or at higher doses.

- Neurotoxicity: Prolonged use may lead to significant neurotoxicity.

- Pain relief: Less potent compared to opioids.

- Pupil dilation

- Seizure: Rare but more likely in susceptible individuals, especially at higher doses or when redosing under physically demanding conditions like dehydration, fatigue, malnutrition, or overheating (requires citation).

- Temporary erectile dysfunction & Orgasm suppression

- Spontaneous bodily sensations: MDMA’s “body high” manifests as a euphoric tingling sensation throughout the body, intensifying as the peak is reached.

- Physical euphoria: Prominent during responsible MDMA use (reasonable dosing and spacing between experiences), leading to profound social and physical disinhibition. However, joy diminishes with tolerance, colloquially called “losing the magic.”

- Enhanced stamina

- Stimulation: MDMA is known for its stimulating and energetic effects, encouraging activities like running, climbing, and dancing. Higher doses may lead to involuntary body movements and reduced motor control. Interestingly, it can also produce wave-like feelings of sedation and relaxation.

- Tactile enhancement: MDMA enhances tactile sensations, making users perceive softness and fuzziness on their skin. Touching soft objects can become exceptionally pleasurable.

- Teeth grinding: Often referred to as “gurning,” more pronounced at moderate to high dosages for some individuals.

- Temperature regulation suppression: Caution against excessive water intake; see the water intoxication and electrolyte imbalance section.

- Vasoconstriction

- Vibrating vision: Eyeballs may spontaneously wobble at high doses, causing blurred vision (nystagmus).

Visual:

- The visual effects of MDMA are less consistent than traditional psychedelics, leading some to dismiss them as myths. They are more likely to occur with pure MDMA at high doses, typically towards the end of the experience, especially when combined with cannabis or when the user has a prior psychedelic experience.

- Enhancements: Mild visual enhancements include colour enhancement and pattern recognition enhancement.

- Suppressions: Double vision, distortions, tracers, symmetrical texture repetition, and geometric patterns. MDMA’s visual geometry resembles psilocin more than LSD. It may induce level 8A visual geometry at higher doses, often described as dark and unsettling.

Hallucinatory States:

- MDMA can induce low and high-level hallucinatory states less consistently than other psychedelics, typically during the peak or offset of the experience.

- External hallucination: Rare, resembling deliriant substances, often themed around memory replays and semi-realistic events.

- Internal hallucinations: Spontaneous breakthroughs at extremely high doses, often as hypnagogic scenarios like memory replays.

- Peripheral information misinterpretation

Cognitive:

- MDMA’s headspace includes mental stimulation, love, empathy, openness, rejuvenation, and euphoria. It produces various cognitive effects typical of entactogens and stimulants.

- Amnesia: Occurs at very high doses.

- Anxiety suppression

- Cognitive euphoria: Strong emotional euphoria due to serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine release.

- Compulsive redosing

- Creativity enhancement

- Decreased libido

- Delirium & Confusion: Occurs with overly high doses, typically linked to temperature dysregulation and overheating in crowded, physically demanding environments.

- Disinhibition

- Ego inflation

- Emotion enhancement

- Empathy, affection, and sociability enhancement: Most pronounced and therapeutic with MDMA, but may diminish with repeated use.

- Focus enhancement: Occurs at low to moderate doses.

- Immersion enhancement

- Increased music appreciation

- Increased sense of humour

- Mindfulness

- Motivation enhancement

- Rejuvenation

- Thought acceleration

- Time compression: Strong feeling of time passing quickly.

Auditory:

- Enhancements

- Hallucinations

- Distortions

- Tinnitus: Rare but can occur when using MDMA alone or in combination with other substances, occasionally accompanied by temporary hearing loss.

Transpersonal:

- Existential self-realization: Less pronounced compared to other hallucinogens but often involves self-affirmation and appreciation for oneself and others.

- Unity and interconnectedness: Often experienced in large crowds at events, described as “becoming one with the crowd,” intensified by music.

After (Comedown):

- The comedown following an entactogen or stimulant experience is typically less enjoyable than the peak, attributed to neurotransmitter depletion. Common effects include anxiety, appetite suppression, brain zaps, cognitive fatigue, depression, derealization, dream suppression or potentiation, sleep paralysis, irritability, motivation suppression, thought deceleration, thought disorganization, suicidal ideation, and wakefulness.

- Some individuals may experience an “afterglow” when MDMA is used responsibly in therapeutic contexts, accompanied by feelings of rejuvenation and euthymia. However, afterglows may transition into comedowns with frequent or excessive use over time.

Dose Relationship:

- The optimal single oral dose for an average user is approximately 90 mg, as the diagram suggests. Note that the percentages at the bottom of the chart may not reflect the current substance content in pills. The concentration of MDMA in ecstasy pills increased between 2010 and 2018. It’s essential to exercise caution and seek updated information regarding substance content.

Names and forms

MDMA, a substance known for its euphoric effects, is commonly referred to by various street names:

- MDMA Pills: These are typically called “Ecstasy” and are often abbreviated as “E,” “X,” or “XTC.” They are most commonly found as illicitly pressed pills or tablets.

- Off-White MDMA Crystals: These are commonly known as “Molly.” Originally, “Molly” referred to crystal or powder MDMA that was believed to be of high purity and free from adulteration. However, it has since become a generic street term for various euphoric stimulants sold in powder or crystal form.

Forms of MDMA: MDMA can be encountered in two primary forms:

- Crystals or Powder (Commonly called Molly): This substance ranges from white to brownish. It can be dissolved, crushed, placed into gel capsules, or wrapped in edible paper (called “parachutes”). MDMA in this form can be taken orally, sublingually, buccally, or insufflated through snorting.

- Pills (Ecstasy): Pills are the most prevalent form in which MDMA is distributed. However, it’s essential to exercise caution when dealing with pills, as they often contain various substances or contaminants. These include MDA, MDEA, amphetamine, methamphetamine, caffeine, 2C-B, mCPP, or synthesis by-products like MDP2P, MDDM, or 2C-H. Pills may also contain other unknown substances, such as research chemicals, prescription drugs, over-the-counter drugs, poisons, or nothing. To ensure safety, it is strongly recommended to use harm reduction measures, such as reagent testing kits, when consuming unknown pills.

Research

MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy:

Dosage Guidelines: For MDMA-assisted therapy, the recommended dosages are as follows:

- 1.1-1.7 mg per kilogram of body weight translates to 80-120 mg for an individual weighing 70 kg.

- Alternatively, you can calculate the dosage by adding 50 milligrams to your body weight in kilograms.

MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy for PTSD: In 2011, a pilot study involving 20 patients yielded promising results in treating post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) using MDMA-assisted psychotherapy. After undergoing two or three sessions of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy, 83% of the patients no longer met the criteria for PTSD. In contrast, only 25% of the control group, where MDMA was replaced with a placebo, experienced the same outcome. These positive results persisted at the two-month and twelve-month follow-up assessments. Notably, the MDMA and placebo groups received non-drug psychotherapy before and after the sessions. During the study, patients were administered a dose of 125 mg of MDMA, followed by a supplemental dose of 62.5 mg after two hours.

After the initial study, patients from the placebo group underwent MDMA-assisted psychotherapy. A long-term follow-up study 2013 involving 19 patients revealed positive results endured even after three years.

In 2017, the FDA granted MDMA a breakthrough therapy designation for treating PTSD. This designation means that if further studies continue to show promise, the FDA may expedite the review process for potential medical use. Phase 3 clinical trials to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of MDMA-assisted therapy have already commenced and are expected to conclude in 2021. This suggests that FDA approval for this treatment could potentially occur as early as 2022.

- R-MDMA: MDMA is typically found and consumed in its racemic form, known as SR-MDMA, which consists of equal parts of S-MDMA and R-MDMA. A study conducted in 2017 discovered that high doses of R-MDMA administered to mice led to increased prosocial behaviour and enhanced fear-extinction learning. Notably, R-MDMA did not induce hyperthermia or display signs of neurotoxicity in contrast to SR-MDMA. This observation is believed to be due to R-MDMA’s lower dopamine release than SR-MDMA. These findings suggest that R-MDMA may represent a safer and more viable therapeutic option than racemic MDMA. However, further research is required to validate this discovery.

Reagent results

Exposing compounds to the reagents gives a colour change which is indicative of the compound under test.

| Marquis | Mecke | Mandelin | Liebermann | Froehde | Gallic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purple – Black | Green – Blue / Black | Purple / Blue – Black | Intense brown – Black | Yellow/green – Dark blue | Green to brown | |

| Robadope | Ehrlich | Hofmann | Simon’s | Zimmermann | Scott | Folin |

| No reaction | No reaction | No reaction | Dark blue | No reaction | No reaction | Orange |

Toxicity

The immediate physical health risks associated with MDMA consumption encompass dehydration, bruxism (teeth grinding), insomnia, hyperthermia (elevated body temperature), and hyponatremia (low blood sodium levels). Notably, MDMA typically does not induce severe or life-threatening effects unless combined with external factors, such as prolonged exposure to high ambient temperature and humidity, extended physical exertion, inadequate water intake, or a lack of acclimatization.

Continuous physical activity without adequate rest or rehydration can lead to high body temperatures. Additionally, excessive sweating resulting from the stimulating and euphoric effects of MDMA can cause individuals to overlook their physical condition.

Diuretics, such as alcohol, can exacerbate these risks by promoting excessive dehydration. Therefore, users are strongly advised to monitor their water intake, avoiding excessive and insufficient consumption and avoiding overexertion to prevent heat-related conditions, including potentially fatal heatstroke.

Toxic Dose: The precise toxic dosage of MDMA remains unknown but is considered significantly higher than the effective therapeutic dose.

Water Intoxication and Electrolyte Imbalance:

Symptoms of water intoxication typically manifest when an individual consumes more than 3-4 litres of water within an hour. Furthermore, one significant cause of fatalities following MDMA use is hyponatremia, which results from excessive water consumption.

Users have reported experiencing xerostomia (dry mouth), possibly contributing to excessive drinking. This heightened water consumption can be attributed to hyperpyrexia, a change in the natural urge to drink, and adherence to harm reduction messages emphasizing the importance of hydration. Higher MDMA doses may lead to difficulties in urination, primarily due to MDMA’s promotion of the release of anti-diuretic hormone (ADH), responsible for regulating urination. Relaxation and applying a warm cloth to the genitals can alleviate this effect. However, MDMA can also cause water retention and electrolyte dilution, increasing the risk of overhydration and water intoxication. This was a significant factor in the tragic case of Leah Betts, who consumed an ecstasy tablet followed by approximately 7 litres of water in just 90 minutes, resulting in water intoxication and hyponatremia, which caused severe brain swelling and irreparable damage.

Individuals may exhibit signs of dehydration, such as dry mouth and sweating, particularly when dancing or in a hot environment.

Preventing Water Intoxication and Electrolyte Imbalance:

Users should have access to hydration, drink according to their thirst, and avoid overconsumption of water.

To prevent hyponatremia, it is recommended to consume fluids that contain sodium, such as sports drinks (typically containing around 20 mM NaCl).

Neurotoxicity:

The extent of MDMA’s neurotoxicity remains a topic of debate. Scientific consensus suggests that while responsible use in a controlled context is physically safe, repeated or high-dosage MDMA administration may result in some form of neurotoxicity.

MDMA administration leads to a subsequent down-regulation of serotonin reuptake transporters in the brain. The rate at which the brain recovers from these serotonergic changes remains unclear. Some studies have indicated lasting serotonergic changes in animals exposed to MDMA, while others suggest potential recovery.

MDMA’s metabolites play a significant role in its neurotoxicity. For example, one metabolite, alpha-methyldopamine (α-Me-DA), was initially believed to contribute to the toxicity of MDMA on serotonin receptors. However, further research revealed that α-Me-DA alone did not cause neurotoxicity. Instead, a metabolite of α-Me-DA, produced in higher concentrations when core body temperature is elevated, is primarily responsible for selective damage to 5-HT receptors triggered by MDMA/MDA. This metabolite is taken up into serotonin receptors by transporters and metabolized by MAO-B into a reactive oxygen species, which can induce neurological damage.

Retracted Article on Dopaminergic Neurotoxicity:

An article titled “Severe Dopaminergic Neurotoxicity in Primates After a Common Recreational Dose Regimen of MDMA” by George A. Ricaurte, initially published in September 2002 in the peer-reviewed journal Science, was later retracted. The article had mistakenly used methamphetamine instead of MDMA in the test.

Cardiotoxicity:

Long-term heavy MDMA use has been linked to cardiotoxicity and potential valvulopathy (heart valve damage) due to its interaction with the 5-HT2B receptor. In one study, 28% of long-term users (2-3 doses per week for six years, with an average age of 24.3 years) developed clinically evident valvular heart disease. Thus, harm reduction practices are strongly recommended when using MDMA.

Dependence and Abuse Potential:

Similar to other stimulants, chronic MDMA use carries a moderate risk of addiction and has a high potential for abuse. Some individuals may develop psychological dependence, leading to cravings and withdrawal symptoms when usage is abruptly discontinued.

Tolerance to MDMA’s effects can develop with prolonged and repeated use, necessitating increasingly larger doses to achieve the same desired results. After a single dose, tolerance reduction typically takes about a month to return to half and 2.5 months to reach baseline levels without further consumption. Additionally, MDMA exhibits cross-tolerance with all dopaminergic and serotonergic stimulants, meaning that using MDMA will diminish the effects of other stimulants.

Dangerous Interactions:

Caution should be exercised when combining MDMA with other substances, as it may lead to dangerous interactions. Some potentially risky combinations include:

- 25x-NBOMe: Combining with MDMA is discouraged due to unpredictable and physically strenuous effects.

- Protease Inhibitors (HIV medications): These drugs may slow MDMA metabolism, leading to longer and more robust effects, potentially harming the liver. Lower doses are recommended.

- 5-MeO-xxT: These tryptamines should be used with caution when mixed with MDMA.

- Alcohol: Combining MDMA and alcohol can lead to dehydration and bodily strain, requiring moderation and hydration.

- Cocaine: Cocaine may negate some desired effects of MDMA while increasing the risk of heart issues.

- DOx: Combining DOx and MDMA can result in overbearing stimulation and heightened anxiety, especially during the come-up phase.

- GHB/GBL: Large amounts of GHB/GBL may overshadow the effects of MDMA during the comedown and risk sudden loss of consciousness.

- MXE: Although there have been reports of serotonergic interactions, taking MXE toward the end of an MDMA experience appears to have fewer issues.

- PCP: Combining PCP with MDMA may heighten stimulation, mania, and psychosis.

- Tramadol: Tramadol is known to lower the seizure threshold, which is particularly concerning when combined with MDMA.

Serotonin Syndrome Risk:

Certain combinations can lead to dangerously high serotonin levels, causing serotonin syndrome, which requires immediate medical attention and can be fatal if left untreated. These combinations include:

- MAOIs (e.g., Syrian rue, banisteriopsis caapi, phenelzine, selegiline, and moclobemide): MAO-B inhibitors can potentiate phenethylamines unpredictably, potentially leading to hypertensive crises.

- SSRIs and SNRIs: These antidepressants may diminish MDMA’s psychological effects while retaining physiological side effects.

- Serotonin Releasers: Other substances that release serotonin include MDMA, 4-FA, methamphetamine, methylone, and αMT.

- AMT

- 2C-T-x

- DXM

- 5-HTP: This supplement, which acts as a serotonin precursor, may cause excessive serotonin levels in the brain when taken with MDMA, leading to serotonin syndrome. It is advisable to wait until the day after MDMA use before consuming 5-HTP.

Legal status

Internationally, MDMA was designated as a Schedule I controlled substance by the UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances in February 1986.

Here is the status of MDMA in various countries:

- Australia: MDMA has been classified as a Schedule 8 (Controlled Drugs) substance in Australia, effective from July 1st, 2023.

- Austria: MDMA is illegal to possess, produce, and sell in Austria under the SMG (Suchtmittelgesetz Österreich).

- Belgium: In Belgium, MDMA is prohibited, and it is illegal to possess, produce, or sell it.

- Brazil: MDMA is illegal to possess, produce, and sell in Brazil under Portaria SVS/MS nº 344.Canada: MDMA is categorized as a Schedule I drug in Canada.

- Denmark: MDMA is illegal to possess, produce, and sell in Denmark.

- Egypt: In Egypt, MDMA is classified as a Schedule III drug.

- Finland: MDMA is illegal to possess, produce, and sell in Finland.

- Germany: Germany has regulated MDMA under Anlage I BtMG (Narcotics Act, Schedule I) since August 1, 1986. It is unlawful to manufacture, possess, import, export, buy, sell, procure, or dispense it without proper authorization.

- Latvia: In Latvia, MDMA is designated as a Schedule I drug.

- Luxembourg: MDMA is considered a prohibited substance in Luxembourg.

- The Netherlands: In the Netherlands, MDMA is illegal to possess, produce, and sell.

- New Zealand: MDMA is classified as a Class B1 drug in New Zealand.

- Norway: MDMA is illegal to possess, produce, and sell in Norway.

- Portugal: In Portugal, it is illegal to produce, sell, or trade MDMA. However, individuals found in possession of small quantities (up to 1 gram) are treated as sick individuals rather than criminals. The drugs are confiscated, and suspects may be required to attend a dissuasion session at the nearest CDT (Commission for the Dissuasion of Drug Addiction) or pay a fine in most cases.

- Russia: MDMA is categorized as a Schedule I prohibited substance in Russia.

- Sweden: MDMA is illegal to possess, produce, and sell in Sweden.

- Switzerland: MDMA is a controlled substance listed explicitly under Verzeichnis D.

- United Kingdom: In the UK, MDMA is classified as a Class A drug.

- United States: MDMA is identified as a Schedule I drug under the Controlled Substance Act. This means it is illegal to manufacture, purchase, possess, process, or distribute without a Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) license.

- Czech Republic: MDMA is classified as a Schedule I controlled substance in the Czech Republic.

FAQ

1. What is MDMA?

MDMA stands for 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine. It is a synthetic drug that alters mood and perception. MDMA is known as “Ecstasy” or “Molly” on the street.

2. How is MDMA typically consumed?

MDMA is most commonly taken orally, either in tablets or capsules. It can also be crushed into a powder, snorted, mixed with liquid, and ingested. Less commonly, it’s used intravenously.

3. What are the effects of MDMA?

MDMA produces feelings of increased energy, pleasure, and emotional closeness. Users often experience enhanced sensory perception, empathy, and a desire to socialize. It can also increase heart rate and body temperature.

4. Is MDMA legal?

The legal status of MDMA varies by country. In many places, it is classified as a controlled substance and is illegal to possess, buy, or sell without a prescription. Always check your local laws.

5. Are there any medical uses for MDMA?

Research into the therapeutic potential of MDMA is ongoing, particularly in treating post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Some countries have approved clinical trials for MDMA-assisted psychotherapy.

6. What are the short-term risks of MDMA use?

Short-term risks include dehydration, bruxism (teeth grinding), insomnia, hyperthermia (elevated body temperature), and hyponatremia (low sodium levels). Overdosing can also occur.

7. Can MDMA be addictive?

While MDMA is not considered physically addictive, some users may develop psychological dependence on it. Frequent use can lead to tolerance, requiring higher doses to achieve the same effects.

8. What are the long-term effects of MDMA use?

Long-term MDMA use can adversely affect mood, memory, and cognitive function. An ongoing debate exists about the potential for neurotoxicity with heavy, repeated use.

9. Are there dangerous drug interactions with MDMA?

Yes, MDMA can interact dangerously with other substances. Mixing it with alcohol or certain medications can increase health risks. Always be cautious and research potential interactions.

10. How can I reduce the risks associated with MDMA use?

To reduce risks, use moderation, stay hydrated but avoid overhydration, test your substances for purity, and avoid mixing with other drugs. Practising harm reduction and being informed are crucial.

11. Is it safe to use MDMA recreationally?

The safety of MDMA use depends on various factors, including dosage, frequency of use, individual health, and the context in which it’s taken. It is never entirely risk-free, and responsible use is essential.

If you or someone you know is struggling with MDMA use or its consequences, seek help from a healthcare professional or a substance abuse support organization. They can provide guidance and resources for treatment and recovery.

References

- Freudenmann, Roland W.; Öxler, Florian; Bernschneider-Reif, Sabine (2006). “Revisiting the Origins of MDMA (Ecstasy): Unearthing the True Story from Original Documents.” In Addiction, 101(9), pp. 1241–1245. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01511.x. ISSN 1360-0443.

- Shulgin, Alexander; Shulgin, Ann (1991). “Chapter 12.” In “PiHKAL: A Chemical Love Story.” Part 1. Transform Press, pp. 66–74. ISBN 0963009605.

- “Merck and the Journey of Ecstasy/MDMA.”

- “Findings from the Global Drug Survey of 2014.”

- World Health Organization, ed. (2004). “Neuroscience of Psychoactive Substance Use and Dependence.” World Health Organization. ISBN 9789241562355.

- Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (2022). “A Placebo-controlled, Randomized, Blinded, Dose Finding Phase 2 Pilot Safety Study of MDMA-assisted Therapy for Social Anxiety in Autistic Adults.” clinicaltrials.gov.

- “MDMA-Assisted Therapy for Anxiety Associated with Life-Threatening Illness (MDA-1).”

- Meyer, J. S. (21 November 2013). “Current Perspectives on 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA).” In Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation, 4, pp. 83–99. doi:10.2147/SAR.S37258.

- Parrott, A. C. (March 2014). “The Potential Dangers of Using MDMA for Psychotherapy.” In Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 46(1), pp. 37–43. doi:10.1080/02791072.2014.873690. ISSN 0279-1072.

- Meyer, J. S. (2013). “3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA): Current Perspectives.” In Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation, 4, pp. 83–99. doi:10.2147/SAR.S37258. ISSN 1179-8467.

- Greene, S. L., Kerr, F., Braitberg, G. (October 2008). “Review article: Amphetamines and Related Drugs of Abuse.” In Emergency Medicine Australasia: EMA, 20(5), pp. 391–402. doi:10.1111/j.1742-6723.2008.01114.x. ISSN 1742-6723.

- Nestler, E. J., Hyman, S. E., Malenka, R. C. (2009). “Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience.” 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 9780071481274.

- Gouzoulis-Mayfrank, E., Daumann, J. (2009). “Neurotoxicity of Drugs of Abuse: The Case of Methylenedioxyamphetamines (MDMA, Ecstasy), and Amphetamines.” In Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 11(3), pp. 305–317. ISSN 1294-8322.

- Karch, Steven (2011). “A Historical Review of MDMA.” “The Open Forensic Science Journal,” 4, pp. 20–24. doi:10.2174/1874402801104010020. ISSN 1874-4028.

- Sessa, B. (2017). “The Psychedelic Renaissance: Reassessing the Role of Psychedelic Drugs in 21st Century Psychiatry and Society.” Muswell Hill Press. ISBN 9781908995278.

- Young, Francis L. (May 22, 1968). “In The Matter Of MDMA Scheduling: Opinion And Recommended Ruling, Findings Of Fact, Conclusions Of Law And Decision Of Administrative Law Judge On Issues Two Through Seven.” Retrieved from maps.org on November 14, 2019.

- “3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine.” Hazardous Substances Data Bank. National Library of Medicine. August 28 2008. Retrieved August 22 2014.

- Miller, G. M. (January 2011). “The Emerging Role of Trace Amine-Associated Receptor 1 in the Functional Regulation of Monoamine Transporters and Dopaminergic Activity: TAAR1 Regulation of Monoaminergic Activity.” In Journal of Neurochemistry, 116(2), pp. 164–176. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07109.x. ISSN 0022-3042.

- Eiden, L. E., Weihe, E. (January 2011). “VMAT2: A dynamic regulator of brain monoaminergic neuronal function interacting with drugs of abuse.” In Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1216, pp. 86–98. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05906.x. ISSN 0077-8923.

- Glennon, R. A., Dukat, M. (January 2011). “Stereoselective Interaction of Novel Analogues of 1-(2,5-Dimethoxy-4-methylphenyl)-2-aminopropane with the Serotonin Transporter.” In Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 54(2), pp. 437–444. doi:10.1021/jm101221t. ISSN 0022-2623.