Beautiful Plants For Your Interior

Summary

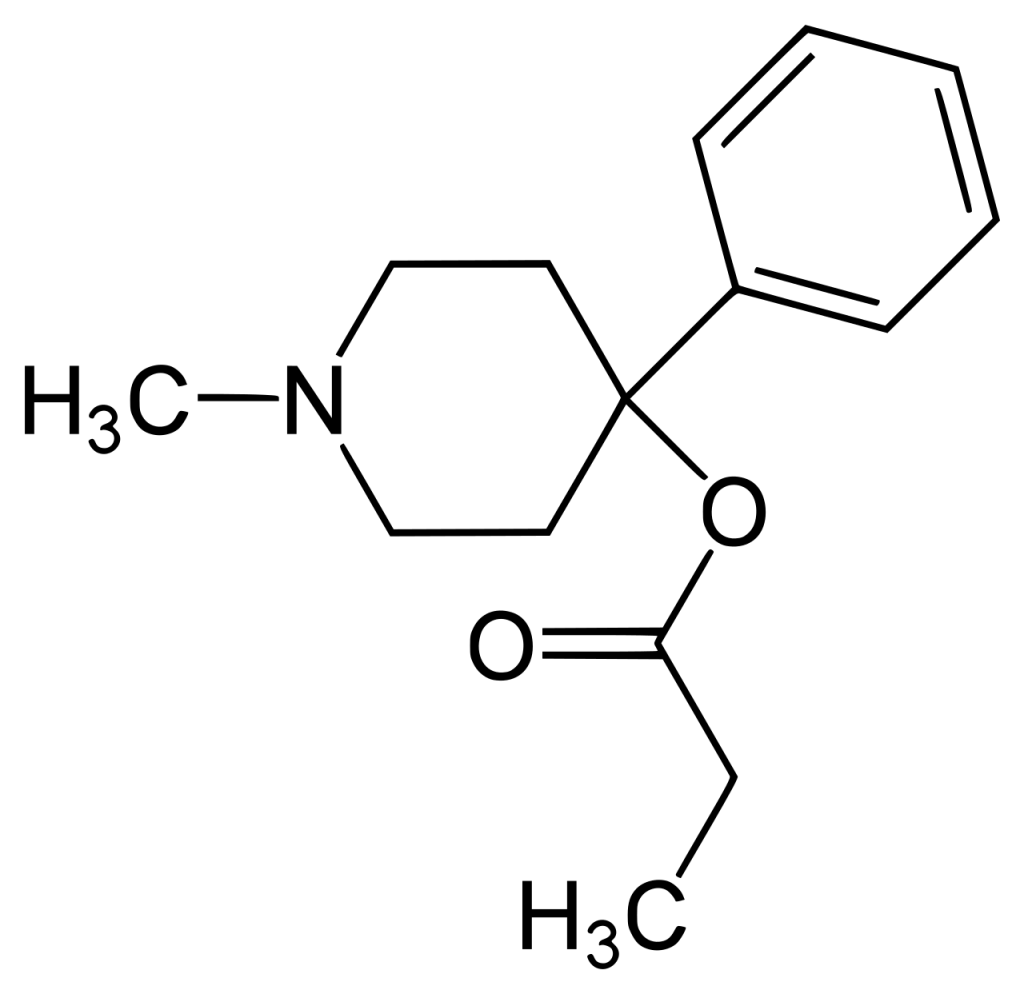

Desmethylprodine, also known as MPPP or Ro 2-0718, is an opioid analgesic initially developed in the 1940s by scientists at Hoffmann-La Roche. In the United States, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) has classified Desmethylprodine as a Schedule I substance, which denotes its controlled and illegal status. Notably, it is an analog of pethidine (meperidine), classified as a Schedule II drug. From a chemical perspective, Desmethylprodine is a reversed ester of pethidine, possessing approximately 70% of the potency of morphine.

Unlike its derivative prodine, Desmethylprodine was not reported to exhibit optical isomerism. Research indicated that it showed approximately 30 times the activity of pethidine and produced a more significant analgesic effect than morphine in rats. Additionally, it was found to induce central nervous system stimulation in mice.

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name | |

| CAS Number | 13147-09-6 |

|---|---|

| PubChem CID | 61583 |

| DrugBank | DB01478 |

| ChemSpider | 55493 |

| UNII | 07SGC963IR |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL279865 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID80157061 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C15H21NO2 |

| Molar mass | 247.338 g·mol−1 |

History

Desmethylprodine, initially synthesized in 1947 at Hoffman-LaRoche Laboratories by Albert Ziering and John Lee, was found to produce effects similar to morphine when administered to rats. This discovery was part of a broader effort to develop synthetic painkillers with lower addictive potential than morphine. Desmethylprodine was essentially a slight variant of pethidine. Still, it was determined to be no more effective than pethidine. It was never brought to market, leading instead to the development of the analgesic alphaprodine (Nisentil, Prisilidine), a closely related compound.

In 1976, a 23-year-old graduate student in chemistry named Barry Kidston, inspired by the research of Ziering and Lee, sought to create a legal recreational drug. He believed that desmethylprodine, being a distinct molecule from pethidine and not covered by existing laws, could offer pethidine-like effects without legal restrictions. Kidston succeeded in synthesizing and using desmethylprodine for several months but eventually experienced symptoms akin to Parkinson’s disease, leading to hospitalization. Physicians were puzzled, as Parkinson’s disease is exceedingly rare in young individuals. However, treatment with L-dopa, a standard drug for Parkinson’s, alleviated his symptoms. L-dopa is a precursor for dopamine, a neurotransmitter whose deficiency leads to Parkinson’s symptoms. Subsequently, it was determined that Kidston’s development of Parkinson’s-like symptoms resulted from a common impurity in the MPPP synthesis known as MPTP (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine). This neurotoxin specifically targets dopamine-producing neurons.

As of 2014, MPPP is classified as a Schedule I substance under the Controlled Substances Act in the United States, with a zero aggregate manufacturing quota. It is also listed under the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs and is subject to similar regulatory controls in most countries as morphine.

Toxic Impurity:

The intermediate tertiary alcohol in the synthesis process can undergo dehydration in acidic conditions when the reaction temperature exceeds 30 °C. Kidston was unaware of this and esterified the intermediate with propionic anhydride at an elevated temperature, resulting in the formation of MPTP as a significant impurity.

1-Methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+), a metabolite of MPTP, induces rapid, irreversible symptoms resembling Parkinson’s disease.[8][9] MPTP is metabolized into the neurotoxin MPP+ by the enzyme MAO-B, predominantly found in glial cells. This selective action leads to the destruction of brain tissue in the substantia nigra region, causing permanent Parkinsonian symptoms.

Analogs

Various structural analogs of desmethylprodine with different N-substituents on the piperidine have been subject to investigation. Some of these analogs exhibit significantly higher in vitro potency compared to desmethylprodine.

FAQ

- What is Desmethylprodine?

- Desmethylprodine, also known as MPPP or Ro 2-0718, is an opioid analgesic drug that was developed in the 1940s. It was initially researched as a potential painkiller.

- Why was Desmethylprodine researched in the 1940s?

- Researchers at Hoffmann-La Roche, where Desmethylprodine was first synthesized, were seeking synthetic painkillers with a reduced risk of addiction compared to traditional opioids like morphine.

- Why is Desmethylprodine classified as a Schedule I drug in the United States?

- In the United States, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) classifies Desmethylprodine as a Schedule I substance, indicating it has a high potential for abuse, no recognized medical use, and poses significant safety risks.

- What were the effects of Desmethylprodine in early research?

- Early research suggested that Desmethylprodine produced effects similar to morphine when administered to rats. However, it was not found to be more effective than pethidine (meperidine), and it was never marketed as a pharmaceutical.

- What is the story behind Barry Kidston’s involvement with Desmethylprodine?

- In 1976, Barry Kidston, a graduate student in chemistry, aimed to create a legal recreational drug inspired by the research on Desmethylprodine. He synthesized and used Desmethylprodine for several months but experienced symptoms similar to Parkinson’s disease, ultimately linked to a toxic impurity in its synthesis.

- What is MPTP, and how is it related to Desmethylprodine?

- MPTP (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine) is a neurotoxin that targets dopamine-producing neurons. Kidston’s development of Parkinson ‘s-like symptoms was attributed to MPTP, which is a byproduct in the synthesis of Desmethylprodine.

- What is the current legal status of Desmethylprodine?

- As of 2014, Desmethylprodine is categorized as a Schedule I substance under the Controlled Substances Act in the United States. It is also subject to regulatory controls in most countries similar to those governing morphine.

- Are there any analogs or related compounds to Desmethylprodine?

- Yes, there have been investigations into structural analogs of Desmethylprodine, some of which have demonstrated significantly higher in vitro potency compared to Desmethylprodine.

References

- US 2765314, Schmidle CJ, Mansfield RC, “Preparation of Esters” (1956) – This patent, issued on 2 October 1956, and assigned to Rohm and Haas, is related to the preparation of esters.

- Reynolds AK, Randall LO (1957) – “Morphine & Allied Drugs” is a reference that provides information about morphine and related drugs.

- Ziering A, Lee J (November 1947) – In this scientific paper, the synthesis of piperidine derivatives, specifically 1,3-dialkyl-4-aryl-4-acyloxypiperidines, is discussed.

- Schwarcz J (2005) – “Aim high: synthetic opiates deliver surprising side effects” is a source that delves into the unexpected side effects of synthetic opiates.

- Gibb, Barry J. (2007) – “The Rough Guide to the Brain” provides insights into various aspects of the brain, including information on opioids.

- “Quotas – 2014” – This source is related to quotas and their allocation in 2014 by the DEA Diversion Control Division.

- Johannessen JN, Markey SP (July 1984) – This scientific article discusses the assessment of the opiate properties of two constituents of a toxic illicit drug mixture.

- Davis GC, Williams AC, Markey SP, Ebert MH, Caine ED, Reichert CM, Kopin IJ (December 1979) – This publication explores chronic Parkinsonism resulting from the intravenous injection of meperidine analogues.

- Wallis C (2001-06-24) – “Surprising Clue to Parkinson’s” is a Time magazine article that uncovers a surprising clue related to Parkinson’s disease.

- Schmidt N, Ferger B (2001) – This scientific article presents neurochemical findings in the MPTP model of Parkinson’s disease.

- Elpern B, Wetterau W, Carabateas P, Grumbach L (1958) – In this scientific publication, the preparation of certain strong analgesics is discussed, particularly 4-acyloxy-1-aralkyl-4-phenylpiperidines.

- Carabateas PM, Grumbach L (September 1962) – This scientific article covers strong analgesics, specifically some 1-substituted 4-phenyl-4-propionoxypiperidines.

- Janssen PA, Eddy NB (February 1960) – This article discusses compounds related to pethidine and new chemical methods for enhancing the analgesic activity of pethidine.