Alprazolam, commonly known as Xanax, is a prescription medication primarily used to treat anxiety and panic disorders. However, it has gained notoriety as a research chemical, often marketed and sold by various online vendors in recent years. This trend raises several concerns that warrant a critical review.

First and foremost, the accessibility of Alprazolam through online sellers is worrisome. While it is a legitimate medication prescribed by a healthcare professional, its availability as a “research chemical” for sale online suggests a lack of regulation and oversight. This raises questions about the product’s quality, purity, and safety. Buyers are left in the dark regarding these substances’ source and manufacturing standards, potentially putting their health at risk.

Moreover, marketing Alprazolam as a research chemical is a thinly veiled attempt to circumvent legal restrictions. By exploiting legal gray areas, these vendors can sell a substance often subject to strict regulations when prescribed by a doctor. This practice not only jeopardizes public health but also undermines the credibility of legitimate research in chemistry and pharmacology.

The term “designer drug” is frequently associated with these online Alprazolam sellers. This label implies that the drug has been chemically modified to evade legal restrictions and is being marketed as a new, legal alternative. Such practices are unethical and potentially dangerous, as these modified compounds may have unpredictable effects on the human body.

Contents

- 1 Summary

- 2 Chemistry

- 3 Pharmacology

- 4 Subjective effects

- 5 Toxicity

- 6 Legal status

- 7 FAQ

- 7.1 1. What is Alprazolam?

- 7.2 2. How does Alprazolam work?

- 7.3 3. What are the common uses for Alprazolam?

- 7.4 4. How is Alprazolam typically dosed?

- 7.5 5. What are the potential side effects of Alprazolam?

- 7.6 6. Is Alprazolam addictive?

- 7.7 7. Can Alprazolam be used for recreational purposes?

- 7.8 8. What precautions should I take when using Alprazolam?

- 7.9 9. Can I abruptly stop taking Alprazolam?

- 7.10 10. Is Alprazolam legal?

- 7.11 11. How should I store Alprazolam?

- 8 References

Summary

Alprazolam, known by its brand name Xanax, belongs to the benzodiazepine class of depressant substances. It is recognized for its distinct effects, which include alleviating anxiety, sedation, reduced inhibitions, and muscle relaxation.

Like other benzodiazepines, alprazolam exerts its influence by binding to specific sites on the GABAA receptor. It is commonly prescribed to manage conditions such as panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and social anxiety disorder (SAD).

Alprazolam is notable for its rapid onset of action, providing prompt relief from symptoms. In cases of panic disorder, approximately ninety percent of the peak effects are typically realized within the initial hour of use, with full peak effects manifesting at around 1.5 to 1.6 hours. Meanwhile, for individuals with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), it may take up to a week to attain the maximum therapeutic benefits.

It’s crucial to emphasize that abruptly discontinuing benzodiazepines can pose serious risks, even life-threatening ones, particularly for those who have been using them regularly over an extended period. Such abrupt cessation can lead to seizures or, in extreme cases, fatalities. Consequently, individuals should follow a tapering regimen, gradually reducing their daily dose over an extended duration, as opposed to suddenly ceasing use. This gradual approach minimizes potential withdrawal effects and ensures a safer transition.

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| show IUPAC name | |

| CAS Number | 28981-97-7 |

| PubChem CID | 2118 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 7111 |

| DrugBank | DB00404 |

| ChemSpider | 2034 |

| UNII | YU55MQ3IZY |

| KEGG | D00225 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:2611 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL661 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID4022577 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.044.849 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C17H13ClN4 |

| Molar mass | 308.77 g·mol−1 |

Chemistry

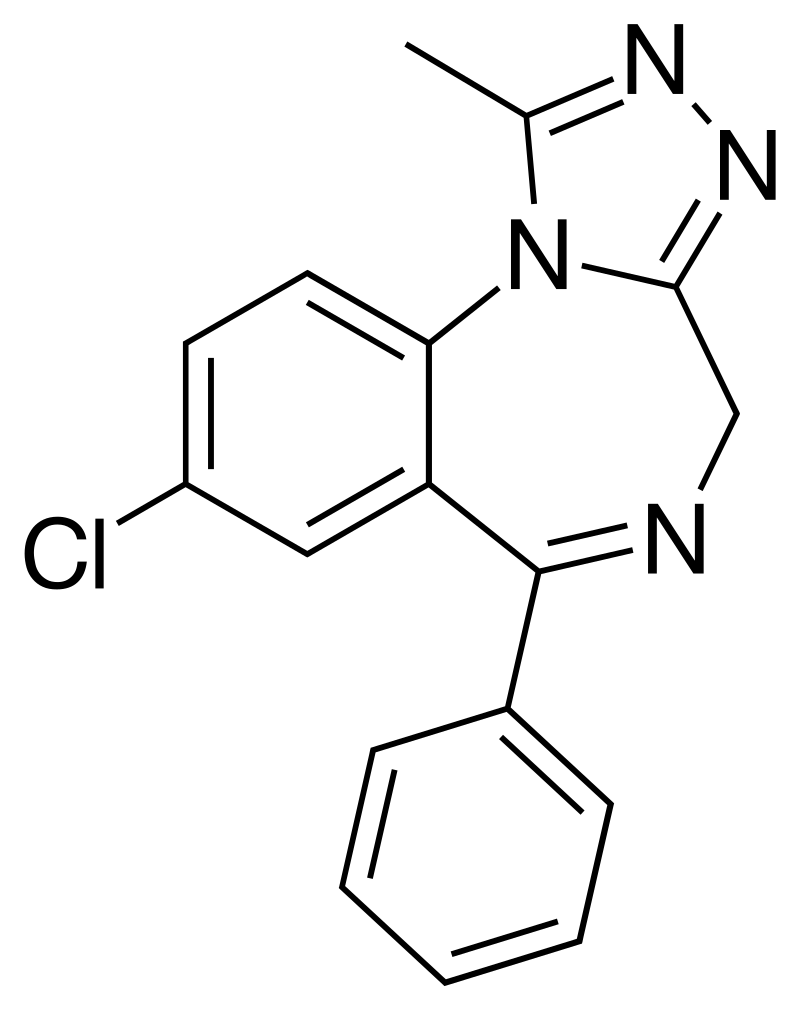

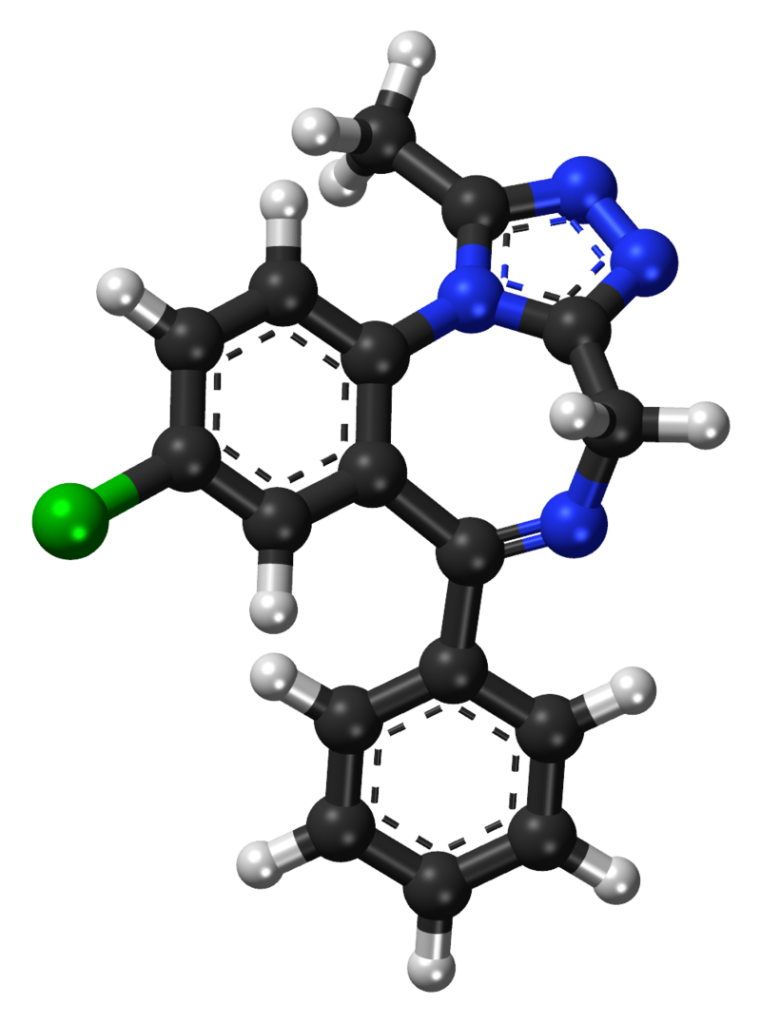

Alprazolam falls within the benzodiazepine drug category. Benzodiazepines are characterized by a benzene ring fused to a diazepine ring, forming a seven-membered ring with nitrogen constituents at R1 and R4 positions. In the case of alprazolam, its benzyl ring is altered with a chlorine group at R8. Additionally, the diazepine ring is connected at R5 to a phenyl ring. Notably, alprazolam features a 1-methylated triazole ring fused to and incorporating R1 and R2 of its diazepine ring. Within the class of benzodiazepines containing this fused triazole ring, it belongs to the subgroup known as triazolobenzodiazepines, identified by the suffix “-zolam.”

Alprazolam carries substitutions, including a phenyl group at position 6, a chlorine atom at position 8, and a methyl group at position 1. It shares similarities with triazolam, with the primary distinction being the absence of a chlorine atom in the ‘ortho’ position of the phenyl ring. This compound exhibits solubility in alcohol but remains insoluble in water.

Pharmacology

Benzodiazepines exert a diverse range of effects by binding to the benzodiazepine receptor site and enhancing the efficiency and impact of the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) through its receptors. Alprazolam is a positive allosteric modulator of the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) type A receptor. This receptor site, notably abundant in the brain, plays a pivotal role in inhibitory functions, resulting in the calming and sedating effects of alprazolam on the central nervous system. It’s worth noting that the anticonvulsant properties of benzodiazepines may, in part or wholly, stem from their interaction with voltage-dependent sodium channels rather than benzodiazepine receptors.

Alprazolam profoundly suppresses the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Its administration has been observed to elevate striatal dopamine levels, yielding effects like anxiety reduction, muscle relaxation, antidepressant action, and anticonvulsant activity. The GABA neurotransmitter and its receptor system mediate the inhibitory and calming impact of alprazolam on the nervous system. Alprazolam’s binding to the GABAA receptor, a chloride ion channel, amplifies the effects of GABA. When GABA engages the GABAA receptor, it initiates the opening of the channel, enabling chloride influx into the cell, thereby enhancing resistance to depolarization. Consequently, alprazolam exerts a depressant effect on synaptic transmission, mitigating anxiety.

The GABAA receptor comprises five subunits from a potential 19, and receptors composed of varying subunit combinations exhibit distinct characteristics, brain locations, and, crucially, benzodiazepine-related activities. Alprazolam and other triazolobenzodiazepines like triazolam, which feature a triazole ring fused to their diazepine ring, appear to possess antidepressant properties. This could be attributed to their structural resemblance to tricyclic antidepressants, characterized by two benzene rings fused to a diazepine ring. Alprazolam shares therapeutic attributes with other benzodiazepines, encompassing anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, muscle relaxant, hypnotic, and amnesic effects; however, its primary application lies in anxiolysis.

When compared to lorazepam, administering alprazolam has been shown to produce a statistically significant increase in extracellular dopamine D1 and D2 concentrations in the striatum.

Subjective effects

The general effects of alprazolam are often described as inducing intense sedation, relaxation, anxiety reduction, and diminished inhibitions.

Disclaimer: The following effects are based on anecdotal user reports and the subjective analysis of contributors to the Subjective Effect Index (SEI). Therefore, they should be regarded with some skepticism. It’s also essential to note that these effects may not consistently or predictably occur, with higher doses more likely to encompass the full range of effects. Furthermore, elevated doses increase the risk of adverse effects, including addiction, severe harm, or even death ☠.

Physical:

- Sedation[citation needed]: Alprazolam can induce profound sedation, leading to extreme lethargy. Users may feel intensely sleep-deprived at higher doses, struggling to stay awake, and eventually succumbing to deep unconsciousness.

- Perception of Bodily Heaviness: Alprazolam may result in sensations of bodily heaviness, ranging from mild motor impairment and difficulty moving at lower doses to complete lethargy or an inability to stand or move at higher doses.

- Appetite Enhancement: Some users report that alprazolam can increase appetite like alcohol, potentially having a synergistic effect with cannabis.

- Muscle Relaxation[citation needed]: Alprazolam produces moderate muscle relaxation, exceeding alcohol but falling short of diazepam (Valium).

- Motor Control Impairment[citation needed]: Alprazolam impairs motor control, akin to alcohol, with higher doses significantly raising the risk of physical injury, such as stumbling or falling over, particularly near stairs or slopes.

- Respiratory Depression[citation needed].

- Dizziness[citation needed]: Dizziness may manifest with higher doses, though generally less pronounced than the dizziness induced by alcohol (commonly referred to as “the spins”).

- Seizure Suppression[citation needed]: Alprazolam exhibits seizure-suppressing properties due to its GABA-mediated inhibitory effects on the nervous system.

Cognitive:

- Analysis Suppression.

- Anxiety Suppression.

- Compulsive Redosing: Alprazolam’s disinhibiting and memory-suppressing effects can lead to users blacking out and repeatedly redosing until their supply is exhausted or they lose consciousness. This behavior poses a risk of fatal overdose, particularly when combined with alcohol or other depressants.

- Confusion: Heavy doses of alprazolam can induce confusion stemming from the drug’s suppression of fundamental cognitive functions like comprehension, memory, and reasoning skills.

- Delusions of Sobriety: Some users may falsely believe they are sober despite clear evidence, such as severe cognitive impairment and difficulty communicating with others, often at heavy dosages.

- Disinhibition.

- Dream Suppression[citation needed]: Benzodiazepines like alprazolam typically inhibit REM sleep and reduce dreaming experience. Sleep under the influence of benzodiazepines is generally reported as deep and refreshing. However, it’s important to note that sleep quality is diminished, making long-term use as a sleep aid unadvisable.

- Emotion Suppression: While alprazolam primarily dampens anxiety, it also blunts other emotions to a lesser extent than antipsychotics.

- Euphoria: Some users report experiencing a notable sense of emotional well-being and comfort while under the influence of alprazolam. However, this effect is not consistently observed and may be more prevalent among individuals with high baseline anxiety levels.

- Language Suppression: Alprazolam can lead to slurred speech and difficulty communicating clearly.

- Memory Suppression[citation needed]: Alprazolam primarily suppresses short-term memory, resulting in forgetfulness and disorganized behavior.

- Amnesia: Higher doses of alprazolam can lead to complete short-term amnesia, similar to the amnesia induced by high alcohol doses.

- Motivation Suppression: Due to alprazolam’s pronounced sedation and lethargy, engaging in activities requiring movement or significant effort can be challenging, especially at higher doses.

- Sleepiness.

- Thought Deceleration.

- Visual:

- Visual Acuity Suppression: Like many depressants, alprazolam is known to cause blurred or reduced visual acuity.

After:

- Rebound Anxiety: Alprazolam and similar anxiety-relieving substances may lead to rebound anxiety, often correlating with the duration of substance influence and the total amount consumed during a given period. This effect can contribute to cycles of dependence and addiction.

- Dream Potentiation.

- Residual Sleepiness: Although benzodiazepines can effectively induce sleep, their effects may persist the following morning, leaving users feeling “groggy” or mentally sluggish for several hours.

- Thought Deceleration.

- Thought Disorganization.

- Irritability.

Paradoxical:

- Paradoxical Reactions: In rare instances, paradoxical reactions to benzodiazepines may occur, including increased seizures (in individuals with epilepsy), heightened anxiety, aggressive behavior, loss of impulse control, irritability, and suicidal tendencies. These effects are more likely in recreational users, individuals with mental disorders, children, and those on high-dosage regimens.

Toxicity

Alprazolam exhibits low toxicity relative to its dosage; however, it can become potentially lethal when mixed with other depressants like alcohol or opioids.

The responsible use of this substance is strongly encouraged, emphasizing harm reduction practices.

In animal studies, the acute oral LD50 in rats ranged from 331 to 2171 mg/kg. In some cases, the administration of massive intravenous doses of alprazolam has resulted in cardiopulmonary collapse.

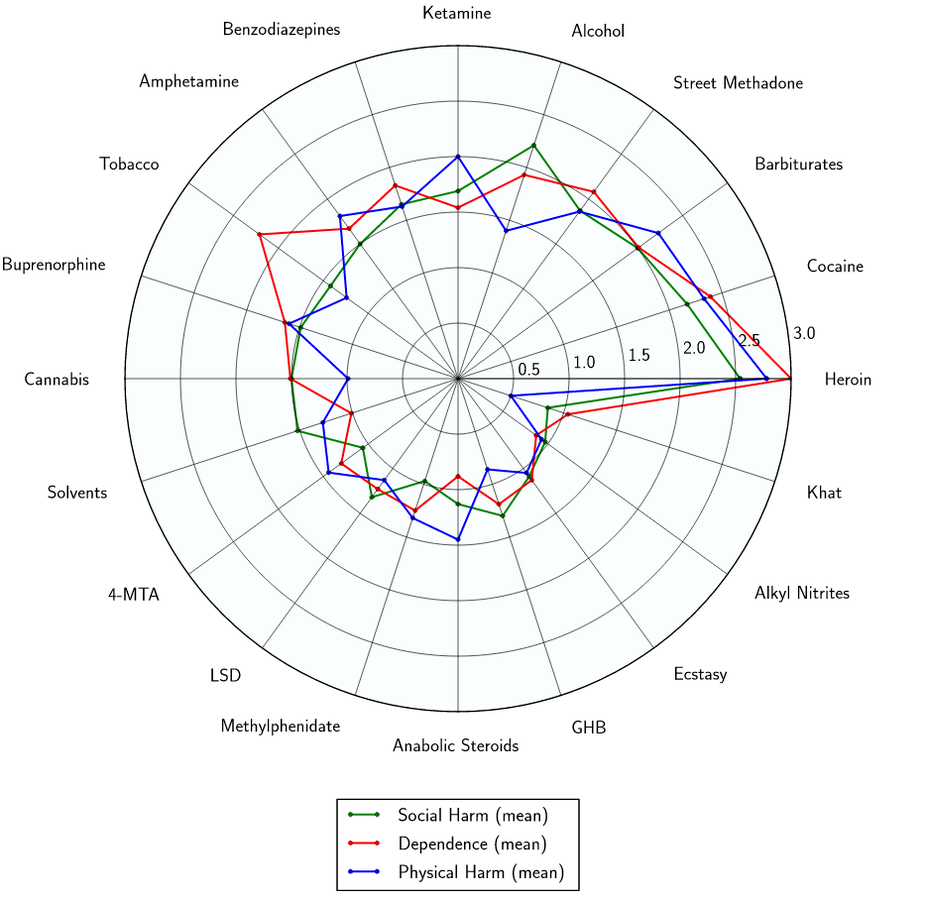

Dependence and Abuse Potential:

Alprazolam is highly physically and psychologically addictive. Tolerance to its sedative-hypnotic effects typically develops within a few days of continuous use. Following cessation, tolerance returns to baseline within 7-14 days, though in certain instances, this may extend for a more extended period, proportional to the duration and intensity of long-term usage. Importantly, alprazolam engenders cross-tolerance with all benzodiazepines, diminishing the effectiveness of other benzodiazepines.

Overdose:

Benzodiazepine overdose can occur with extremely high doses or, more commonly, combined with other depressants. The risk is particularly pronounced when combined with other GABAergic depressants like barbiturates and alcohol, as they operate similarly but bind to distinct sites on the GABAA receptor, leading to significant cross-potentiation. Benzodiazepine overdose is a medical emergency that may result in coma, permanent brain damage, or even death if not promptly treated. Symptoms may include severe slurred speech, confusion, delusions, respiratory depression, and unresponsiveness, sometimes resembling a sleepwalking state. Impaired judgment during overdose may lead to further substance consumption, a behavior less commonly observed with other substances during overdose. Benzodiazepine overdoses are generally treatable in a hospital setting, often with positive outcomes. Treatment primarily involves supportive care, though overdoses may be managed with flumazenil, a GABAA antagonist[22], or additional interventions like adrenaline injections if other substances are involved.

Discontinuation:

The discontinuation of benzodiazepines is notoriously challenging and potentially life-threatening for individuals with regular use. It is strongly recommended to taper the dose gradually over several weeks to avoid elevated blood pressure, seizures, or even death. Substances that lower the seizure threshold, such as tramadol, should be avoided during withdrawal. Abrupt cessation may result in rebound stimulation, manifesting as anxiety, insomnia, and restlessness. If one intends to discontinue after prolonged use, it is safest to reduce the daily dose by a minimal amount over a couple of weeks, approaching abstinence. In the case of short half-life benzodiazepines like alprazolam or etizolam, they can be substituted with longer-acting varieties like diazepam or clonazepam to alleviate symptoms, although some may persist.

Dangerous Interactions:

Caution is warranted when combining psychoactive substances, as certain combinations can abruptly become dangerous or even life-threatening. Conducting independent research to ensure the safety of combining multiple substances is essential. Some of the following interactions have been sourced from TripSit:

Depressants (1,4-Butanediol, 2M2B, alcohol, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, GHB/GBL, methaqualone, opioids):

This combination potentiates muscle relaxation, amnesia, sedation, and respiratory depression, increasing the risk of unconsciousness and life-threatening respiratory suppression, mainly if nausea or vomiting occurs.

Dissociatives:

Combining these substances can unpredictably amplify amnesia, sedation, motor control loss, and delusions, potentially leading to a sudden loss of consciousness accompanied by dangerous respiratory depression. If nausea or vomiting occurs, users should try to sleep in the recovery position or seek assistance.

Stimulants:

Stimulants can mask the sedative effects of depressants, potentially leading to an underestimated level of intoxication. Once the stimulant effects wear off, the depressant effects can intensify, resulting in severe disinhibition, motor control loss, and blackouts. This combination also risks severe dehydration if fluid intake is not closely monitored, requiring strict dosing schedules to minimize risks.

Legal status

Alprazolam’s legal status varies internationally, with each country imposing its regulations:

United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances: Alprazolam is classified as a Schedule IV substance under this international convention.

Australia: Originally categorized as Schedule 4 (prescription-only), as of January 2014, it became a Schedule 8 medication, subject to more stringent prescription requirements.

Austria: Alprazolam is legal for medical use under the AMG (Arzneimittelgesetz Österreich) but is illegal when sold or possessed without a prescription under the SMG (Suchtmittelgesetz Österreich).

Czechia: Alprazolam is a Schedule IV (List 7) substance, available exclusively with a prescription “without a blue stripe.”

Germany: Alprazolam has been controlled under Anlage III BtMG (Narcotics Act, Schedule III) since August 1, 1986. It can only be prescribed using a narcotic prescription form, except for preparations containing up to 1 mg of triazolam in each dosage form.

Ireland: Alprazolam is classified as a Schedule 4 medicine.

Italy: Alprazolam is a Schedule IV drug (Tabella 4) under the “Testo unico sulla droga (D.P.R. 309/90).” Medical prescriptions for its use fall under Pharmaceuticals section B and E (Tabella medicinali sezione B ed E).

Russia: Since 2013, alprazolam is a Schedule III controlled substance in Russia.

Sweden: Alprazolam is a prescription drug in List IV (Schedule 4) under the Narcotics Drugs Act (1968).

Switzerland: Alprazolam is a controlled substance listed explicitly under Verzeichnis B, with medicinal use permitted.

Turkey: Alprazolam is classified as a ‘green prescription’ only substance and is illegal when sold or possessed without a prescription.

The Netherlands: Alprazolam is a List 2 substance of the Opium Law and is available for prescription.

United Kingdom: Alprazolam is a controlled drug listed under Schedule IV, Part I (CD Benz POM) of the Misuse of Drugs Regulations 2001. Possession is allowed with a valid prescription. The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 classifies it as a Class C drug, making it illegal to possess without a prescription.

United States: Alprazolam is a prescription medication assigned to Schedule IV of the Controlled Substances Act by the DEA.

FAQ

1. What is Alprazolam?

- Alprazolam, commonly known by its brand name Xanax, is a medication from the benzodiazepine class. It is primarily prescribed to treat anxiety and panic disorders.

2. How does Alprazolam work?

- Alprazolam acts on the central nervous system by enhancing the effects of a neurotransmitter called gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). This results in a calming and soothing effect, reducing anxiety and panic symptoms.

3. What are the common uses for Alprazolam?

- Alprazolam is prescribed for treating anxiety disorders, panic disorders, and sometimes for other conditions like insomnia. It can also be used as a short-term solution for anxiety associated with depression.

4. How is Alprazolam typically dosed?

- The dosage depends on the individual and their specific condition. Typically, it is taken in divided doses throughout the day. Your healthcare provider will determine the appropriate dosage for your needs.

5. What are the potential side effects of Alprazolam?

- Common side effects include drowsiness, dizziness, dry mouth, and changes in appetite. Less common but more severe side effects can include memory problems, mood changes, and allergic reactions. Always consult your healthcare provider if you experience any unusual symptoms.

6. Is Alprazolam addictive?

- Alprazolam can be addictive, mainly when used for extended periods or in higher doses than prescribed. It’s essential to take it only as directed by your healthcare provider and to avoid misuse.

7. Can Alprazolam be used for recreational purposes?

- Using Alprazolam recreationally is illegal and highly discouraged. It can lead to addiction, overdose, and severe health risks.

8. What precautions should I take when using Alprazolam?

- Never mix Alprazolam with alcohol or other drugs without your doctor’s approval. Inform your healthcare provider of any other medications or supplements you’re taking. Do not drive or operate heavy machinery while under the influence of Alprazolam, as it impairs cognitive and motor skills.

9. Can I abruptly stop taking Alprazolam?

- No, you should not stop taking Alprazolam suddenly, especially if you’ve been using it for an extended period. Doing so can lead to withdrawal symptoms, which can be severe. Consult your healthcare provider to create a tapering plan for discontinuation.

10. Is Alprazolam legal?

- Alprazolam is a prescription medication and is legal when used as prescribed by a healthcare provider. Using it without a prescription or for non-medical purposes is illegal in many countries.

11. How should I store Alprazolam?

- Keep Alprazolam secure, out of reach of children and unauthorized users. Store it at room temperature, away from moisture and heat.

References

- Mandrioli, R., Mercolini, L., Raggi, M. A. (October 2008). “Analyzing Benzodiazepine Metabolism: An In-Depth Perspective.” Current Drug Metabolism, 9(8), 827–844. doi:10.2174/138920008786049258.

- Nuss, P. (17 January 2015). “GABA Neurotransmission Disturbance and its Connection to Anxiety Disorders.” Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 11, 165–175. doi:10.2147/NDT.S58841.

- FDA-approved labeling for Xanax revision 08/23/2011. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/018276s045lbl.pdf.

- Smith, R. B., Kroboth, P. D., Vanderlugt, J. T., Phillips, J. P., Juhl, R. P. (1984). “Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Alprazolam Following Oral and IV Administration.” Psychopharmacology, 84(4), 452–456. doi:10.1007/BF00431449.

- Sheehan, D. V., Sheehan, K. H., Raj, B. A. (2007). “Comparing the Onset of Action of Alprazolam-XR to Alprazolam-CT in Panic Disorder.” Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 40(2), 63–81.

- Verster, J. C., Volkerts, E. R. (7 June 2006). “A Comprehensive Review of Alprazolam: Clinical Pharmacology, Efficacy, and Behavioral Toxicity.” CNS Drug Reviews, 10(1), 45–76. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2004.tb00003.x.

- Lann, M. A., Molina, D. K. (June 2009). “A Fatal Case of Benzodiazepine Withdrawal.” The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology, 30(2), 177–179. doi:10.1097/PAF.0b013e3181875aa0.

- Kahan, M., Wilson, L., Mailis-Gagnon, A., Srivastava, A. (November 2011). “Canadian Guideline for Safe Benzodiazepine Use in Chronic Noncancer Pain: Appendix B-6 on Benzodiazepine Tapering.” Canadian Family Physician, 57(11), 1269–1276.

- Haefely, W. (29 June 1984). “Understanding Benzodiazepine Interactions with GABA Receptors.” Neuroscience Letters, 47(3), 201–206. doi:10.1016/0304-3940(84)90514-7.

- McLean, M. J., Macdonald, R. L. (February 1988). “Benzodiazepines and Their Effects on Spinal Cord Neurons.” The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 244(2), 789–795.

- Bentué-Ferrer, D., Reymann, J. M., Tribut, O., Allain, H., Vasar, E., Bourin, M. (February 2001). “Role of Dopaminergic and Serotonergic Systems in the Behavioral Effects of Low-Dose Alprazolam and Lorazepam.” European Neuropsychopharmacology, 11(1), 41–50. doi:10.1016/s0924-977x(00)00137-1.

- Hitchings, A., Lonsdale, D., Burrage, D., Baker, E. (2014). “Top 100 Drugs: Clinical Pharmacology and Practical Prescribing.” Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 9780702055164.

- Barbee, J. G. (October 1993). “Memory, Benzodiazepines, and Anxiety: Integrating Theory and Clinical Perspectives.” The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 54 Suppl, 86–97; discussion 98–101.

- Goyal, Sarita. “Drugs and Dreams.” Indian Journal of Clinical Practice. Read here.

- Saïas, T., Gallarda, T. (September 2008). “Paradoxical Aggressive Reactions to Benzodiazepine Use: A Comprehensive Review.” L’Encephale, 34(4), 330–336. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2007.05.005.

- Paton, C. (December 2002). “Benzodiazepines and Disinhibition: A Review.” Psychiatric Bulletin, 26(12), 460–462. doi:10.1192/pb.26.12.460.

- Bond, A. J. (1 January 1998). “Drug-Induced Behavioral Disinhibition.” CNS Drugs, 9(1), 41–57. doi:10.2165/00023210-199809010-00005.

- Drummer, O. H. (February 2002). “Benzodiazepines – Effects on Human Performance and Behavior.” Forensic Science Review, 14(1–2), 1–14.

- Nutt, D., King, L. A., Saulsbury, W., Blakemore, C. (24 March 2007). “Development of a Rational Scale to Assess the Harm of Drugs of Potential Misuse.” The Lancet, 369(9566), 1047–1053. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4.

- Janicak, P. G., Marder, S. R., Pavuluri, M. N. (25 October 2010). “Principles and Practice of Psychopharmacotherapy.” Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9781605475653.

- Hoffman, E. J., Warren, E. W. (September 1993). “Flumazenil: A Benzodiazepine Antagonist.” Clinical Pharmacy, 12(9), 641–656; quiz 699–701.

- List of Psychotropic Substances under International Control. Read here.

- Alprazolam is to be Rescheduled for Next Year. [Read here](http://www.australiandoctor.com.au/news/latest-news