As of my last knowledge update in September 2021, Para-Methoxyamphetamine (PMA) was considered a relatively uncommon and risky designer drug within the amphetamine class. Please note that the market situation may have evolved since then.

PMA, often misrepresented as MDMA (Ecstasy), posed significant dangers due to its delayed onset of effects and higher toxicity levels. Back then, consumers needed extreme caution when attempting to buy substances claiming to be MDMA, as they could unknowingly acquire PMA, which carried a higher risk of adverse reactions, including severe overheating and serotonin syndrome.

In the online marketplace, PMA was occasionally offered for sale by unscrupulous sellers and vendors who may have labelled it as MDMA or as a “research chemical.” This misrepresentation could put users at significant risk, as PMA has a narrower dose-response window than MDMA, making it easier to overdose accidentally.

However, the legal status of PMA and other designer drugs varied widely across different jurisdictions, contributing to the complex and ever-changing market landscape.

Given the potential risks associated with PMA, individuals must prioritize safety, seek accurate information, and comply with local laws and regulations. Additionally, it’s essential to stay updated on the latest developments and emerging substances in the designer drug market.

Contents

- 1 Summary

- 2 Adverse effects

- 3 Overdose

- 4 Pharmacology

- 5 History

- 6 Society and culture

- 7 FAQ

- 7.1 1. What is Para-Methoxyamphetamine (PMA)?

- 7.2 2. Is PMA legal?

- 7.3 3. What are the effects of PMA?

- 7.4 4. What are the risks associated with PMA use?

- 7.5 5. How can I reduce the risks associated with PMA use?

- 7.6 6. Is PMA the same as MDMA (Ecstasy)?

- 7.7 7. What should I do if I or someone I know experiences adverse effects from PMA use?

- 7.8 8. Where can I find help and support for substance abuse issues?

- 8 References

Summary

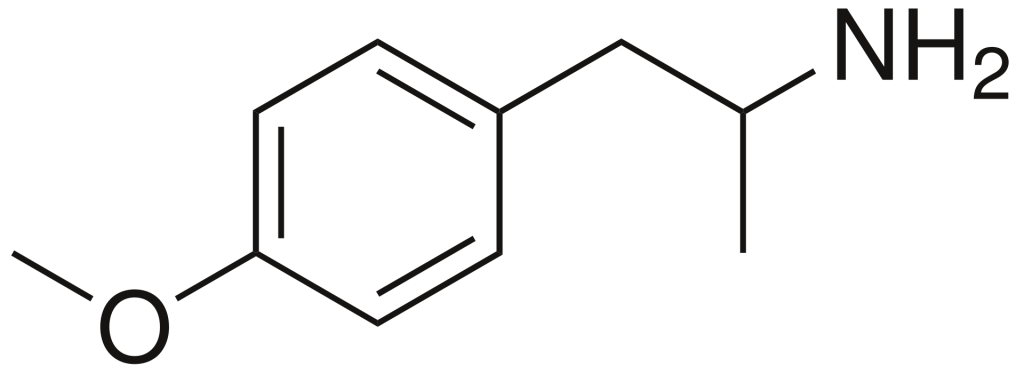

Para-methoxyamphetamine (PMA), also recognized as 4-methoxyamphetamine (4-MA), belongs to the amphetamine class of designer drugs and exhibits serotonergic effects. In contrast to other compounds within this drug family, PMA does not induce stimulant, euphoric, or entactogenic sensations but instead behaves more akin to an antidepressant, albeit with some psychedelic properties.

Notably, PMA has been identified in tablets falsely marketed as MDMA (commonly referred to as ecstasy), even though its effects diverge significantly from those of MDMA. The repercussions of such misrepresentation have frequently led to hospitalizations and fatalities among unsuspecting users. PMA is typically synthesized from anethole, the aromatic compound found in anise and fennel, primarily because the precursor material for MDMA, safrole, has become less accessible due to law enforcement efforts. This has prompted illicit drug manufacturers to turn to anethole as an alternative source for production.

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name | |

| CAS Number | 64-13-1 |

|---|---|

| PubChem CID | 31721 |

| DrugBank | DB01472 |

| ChemSpider | 29417 |

| UNII | OVB8F8P39Q |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL278663 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID7040578 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.525 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C10H15NO |

| Molar mass | 165.236 g·mol−1 |

Adverse effects

PMA has been linked to a range of adverse reactions, including fatalities. Ingesting PMA can lead to effects reminiscent of hallucinogenic amphetamines, including an accelerated and irregular heartbeat, blurred vision, and a profound sense of intoxication that is often unpleasant. Individuals may experience discomforting effects such as nausea, vomiting, severe hyperthermia, and hallucinations at higher doses. Notably, the effects of PMA appear to be significantly more unpredictable and variable among individuals compared to MDMA. Sensitive individuals might face life-threatening consequences from a dose of PMA that would only mildly affect a less susceptible person.

Furthermore, the combination of PMA with MDMA can produce a synergistic effect that is particularly hazardous. Due to PMA’s slow onset of effects, there have been instances where individuals mistakenly believed that a pill containing PMA was inactive, leading them to consume a pill containing MDMA subsequently. This misunderstanding has resulted in several tragic fatalities.

Overdose

Overdosing on PMA can escalate into a critical medical emergency, often occurring even with only slight deviations from the typical recreational dose range. This risk is heightened when PMA is combined with other stimulant substances like cocaine or MDMA. Recognizable symptoms include pronounced hyperthermia, tachycardia, hypertension, agitation, confusion, and seizures.

PMA overdose is also distinctive in its tendency to induce hypoglycemia and hyperkalemia, which can help differentiate it from MDMA overdose. Complications may escalate to more severe conditions like rhabdomyolysis and cerebral haemorrhage, sometimes necessitating emergency surgical interventions. Unfortunately, no specific antidote for PMA overdose exists, so treatment focuses on addressing symptoms.

Typical therapeutic approaches involve external cooling measures and internal cooling via intravenous infusion of cooled saline. Initial control of seizures often requires benzodiazepines, with more potent anticonvulsants like phenytoin or thiopental considered if seizures persist. Blood pressure can be managed by combining alpha and beta blockers or other medications like nifedipine or nitroprusside. Serotonin antagonists and dantrolene may also be administered as needed.

Despite the gravity of the condition, prompt and appropriate treatment typically results in favourable outcomes. However, patients presenting with a core body temperature exceeding 40 °C at the outset tend to have a poorer prognosis.

Pharmacology

PMA functions as a selective serotonin-releasing agent (SSRA) but exerts weaker effects on dopamine and norepinephrine transporters. However, compared to MDMA, its serotonin-releasing potency is significantly lower, exhibiting properties more akin to those of a reuptake inhibitor. In rodent studies, PMA induces robust hyperthermia while causing only modest hyperactivity and serotonergic neurotoxicity, notably less than MDMA and primarily at very high doses. Consequently, rodents do not self-administer PMA, unlike amphetamine and MDMA. Anecdotal human reports suggest that PMA lacks substantial euphoric effects and may even induce dysphoria.

Additionally, PMA has been identified as a potent, reversible inhibitor of the enzyme MAO-A, with no significant impact on MAO-B. Combining this property with serotonin release likely contributes to its high lethality potential.

The significant elevation of body temperature associated with PMA is suspected to arise from its dual action of inhibiting MAO-A and releasing substantial amounts of serotonin, potentially leading to serotonin syndrome. Notably, the concurrent use of amphetamines, particularly serotonergic analogues like MDMA, with MAOIs is strongly contraindicated. Different amphetamines and adrenergic compounds can lead to varied effects on body temperature, with some favouring euphoric activity or peripheral vasoconstriction over pronounced hyperthermia.

PMA’s impact on the hypothalamus appears more pronounced than that of MDMA and similar drugs like ephedrine, resulting in rapid increases in body temperature, a significant factor contributing to PMA-related fatalities. Individuals consuming PMA have been known to employ strategies such as removing clothing, taking cold showers, using wet towels, and even shaving their hair to mitigate overheating.

History

PMA appeared in the early 1970s when it was intentionally utilized as a substitute for the hallucinogenic effects of LSD. At the time, it garnered street names like “Chicken Powder” and “Chicken Yellow” and was associated with drug overdose deaths in the United States and Canada. These fatal incidents typically involved dosages ranging in the hundreds of milligrams. Notably, from 1974 until the mid-1990s, no recorded fatalities were attributed to PMA.

In the mid-1990s, several deaths initially reported as MDMA-induced in Australia are now believed to have been caused by unwitting ingestion of PMA instead of MDMA, as users were unaware of the substitution. Since then, there have been numerous PMA-related fatalities worldwide.

In July 2013, Scotland witnessed seven fatalities linked to PMA-containing tablets mislabeled as ecstasy and bore a Rolex crown logo.[10] During the same period, several deaths in Northern Ireland, particularly in East Belfast, were also linked to “Green Rolex” pills.

Subsequently, in 2014, 2015, and early 2016, PMA disguised as ecstasy was implicated in additional fatalities in the United States, United Kingdom, Netherlands, and Argentina. These pills, containing PMA, were often described as red triangular tablets featuring a “Superman” logo.

A newer variation of these tablets, known as the “Red Ferrari” pills, emerged and was reported in Germany and Norway from 2016 to 2017. These tablets retained the iconic Superman logo.

Society and culture

International

PMA is classified as a Schedule I drug under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.

Australia

In Australia, PMA is categorized as a Schedule 9 prohibited substance according to the Poisons Standard (October 2015). A Schedule 9 substance has the potential for misuse or abuse, and its manufacture, possession, sale, or use is generally prohibited by law, except for authorized medical or scientific research, analytical, teaching, or training purposes, subject to approval by Commonwealth and State or Territory Health Authorities.

Finland

PMA is included in the government decree amending the government decree on substances, preparations, and plants classified as narcotic drugs.

Germany

PMA is listed in Appendix 1 of the Betäubungsmittelgesetz, making its ownership and distribution illegal in Germany.

Netherlands

On June 13, 2012, Edith Schippers, Dutch Minister of Health, Welfare, and Sport, revoked the legality of PMA in the Netherlands due to five reported deaths that year.

United Kingdom

PMA is classified as a Class A drug in the United Kingdom.[citation needed]

United States

In the United States, PMA is designated as a Schedule I hallucinogen under the Controlled Substances Act.

Economics

Distribution

Since PMA is distributed through the same channels as MDMA tablets, the risk of severe injury, hospitalization, or death from ecstasy use increases significantly when batches of ecstasy pills containing PMA enter a specific area. PMA pills can come in various colours or imprints, making it impossible to determine the drug(s) they may contain based on appearance alone. Notable batches of pills containing PMA have included Louis Vuitton, Mitsubishi Turbo, Blue Transformers, Red/Blue Mitsubishi, and Yellow Euro pills. PMA has also been discovered in powder form.[50]

Analogues

Four analogues of PMA are known to be sold on the black market, including PMMA, PMEA, 4-ETA, and 4-MTA. These analogues are the N-methyl, N-ethyl, 4-ethoxy, and 4-methylthio versions of PMA. PMMA and PMEA are reported to be less dangerous and more “ecstasy-like” than PMA, but they can still cause nausea and hyperthermia at slightly higher doses. 4-EtOA was briefly available in Canada in the 1970s, with limited information about its effects. However, 4-MTA is even more hazardous than PMA, causing strong serotonergic effects, intense hyperthermia, and little to no euphoria, and it has been linked to several deaths in the late 1990s.

FAQ

1. What is Para-Methoxyamphetamine (PMA)?

Para-methoxyamphetamine, commonly referred to as PMA, is a synthetic psychoactive substance known for its stimulant and hallucinogenic effects. It is chemically related to amphetamines and belongs to the substituted amphetamines class of drugs.

2. Is PMA legal?

The legal status of PMA varies by country. In many nations, including the United States and several European countries, PMA is classified as a controlled or prohibited substance due to its potential for abuse and health risks. Always check your local laws and regulations for the most up-to-date information on its legality.

3. What are the effects of PMA?

PMA’s effects can include increased energy, alertness, and euphoria, similar to other stimulant drugs. However, it is also known for its hallucinogenic properties, which can lead to altered perceptions, vivid sensory experiences, and, in some cases, severe adverse reactions such as hyperthermia, agitation, and hallucinations.

4. What are the risks associated with PMA use?

PMA use carries several risks, including:

- Overdose: PMA is more potent than MDMA (ecstasy) and can be toxic at lower doses, potentially leading to overdose.

- Hyperthermia: PMA can cause dangerous increases in body temperature, resulting in heatstroke and organ failure.

- Cardiovascular Issues can strain the cardiovascular system, leading to heart problems and high blood pressure.

- Serotonin Syndrome: PMA can lead to serotonin syndrome, a potentially life-threatening condition characterized by excessive serotonin levels in the brain.

5. How can I reduce the risks associated with PMA use?

The safest way to avoid the risks associated with PMA is not to use it. However, if you choose to use substances, consider harm-reduction strategies such as:

- Testing: Use drug testing kits to confirm the contents of substances you plan to consume and avoid adulterated or mislabeled drugs.

- Start with a small dose: If you decide to use PMA, start with a low dose to minimize the risk of overdose or adverse reactions.

- Stay hydrated: Drink water but avoid overhydration. Extreme water consumption can lead to a dangerous condition called hyponatremia.

- Use in a safe environment: Be with trusted friends in a familiar and safe setting to reduce the risk of harm.

6. Is PMA the same as MDMA (Ecstasy)?

No, PMA and MDMA are different substances. While both are stimulant and hallucinogenic drugs, PMA is more potent and has a different chemical structure. It is essential to distinguish between these substances as they have varying effects and risks.

7. What should I do if I or someone I know experiences adverse effects from PMA use?

If you or someone you know experiences adverse effects after using PMA, seek medical attention immediately. Do not hesitate to call emergency services. It’s crucial to address potential health emergencies promptly.

8. Where can I find help and support for substance abuse issues?

If you or someone you know is struggling with substance abuse, various resources are available, including local addiction helplines, support groups, and addiction treatment centres. Reach out to a healthcare professional or a trusted organization specializing in addiction treatment for guidance and assistance.

Please note that the information provided here is for educational purposes only, and it is essential to prioritize safety and make informed decisions regarding substance use.

References

- Anvisa (July 24, 2023). “RDC Nº 804 – Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial” [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 804 – Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Published in Diário Oficial da União (July 25, 2023). Archived from the original on August 27, 2023. Retrieved on August 27, 2023.

- Drug Enforcement Administration (October 2000). “The Hallucinogen PMA: Dancing With Death.”

- Shulgin AT, Shulgin A (1991). “#97 4-MA.” From “Pihkal: A Chemical Love Story” published by Transform Press. ISBN 978-0-9630096-0-9.

- Karlis S (April 7, 2008). “Warning of possible shift to killer drug.” Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax. Retrieved on June 29, 2008.

- Corrigall WA, Robertson JM, Coen KM, Lodge BA (January 1992). “The reinforcing and discriminative stimulus properties of para-ethoxy- and para-methoxyamphetamine.” Published in “Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior,” 41(1), 165–169.

- Preve M, Suardi NE, Godio M, Traber R, Colombo RA (April 2017). “Paramethoxymethamphetamine (Mitsubishi turbo) abuse: Case report and literature review.” Published in “European Psychiatry,” 41(S1), s875.

- Hegadoren KM, Martin-Iverson MT, Baker GB (April 1995). “Comparative behavioural and neurochemical studies with a psychomotor stimulant, an hallucinogen and 3,4-methylenedioxy analogues of amphetamine.” Published in “Psychopharmacology,” 118(3), 295–304.

- Winter JC (February 1984). “The stimulus properties of para-methoxyamphetamine: a nonessential serotonergic component.” Published in “Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior,” 20(2), 201–203.

- “EcstasyData.org: Results: Lab Test Results for Recreational Drugs.”

- Davies C (July 10, 2013). “Warning over fake ecstasy tablets after seven people die in Scotland.” The Guardian. Retrieved on July 10, 2013.

- Barrell R (January 2, 2015). “Four Dead Amid Fears Of Dodgy Batch Of ‘Superman’ Ecstasy Hitting The UK.” HuffPost UK.

- Byard RW, Gilbert J, James R, Lokan RJ (September 1998). “Amphetamine derivative fatalities in South Australia–is ‘Ecstasy’ the culprit?” Published in “The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology,” 19(3), 261–265.

- Waumans D, Bruneel N, Tytgat J (April 2003). “Anise oil as para-methoxyamphetamine (PMA) precursor.” Published in “Forensic Science International,” 133(1–2), 159–170.

- Martin TL (October 2001). “Three cases of fatal paramethoxyamphetamine overdose.” Published in “Journal of Analytical Toxicology,” 25(7), 649–651.

- Becker J, Neis P, Röhrich J, Zörntlein S (March 2003). “A fatal paramethoxymethamphetamine intoxication.” Published in “Legal Medicine,” 5(Suppl 1), S138–S141.

- Smets G, Bronselaer K, De Munnynck K, De Feyter K, Van de Voorde W, Sabbe M (August 2005). “Amphetamine toxicity in the emergency department.” Published in “European Journal of Emergency Medicine,” 12(4), 193–197.

- Lora-Tamayo C, Tena T, Rodríguez A, Moreno D, Sancho JR, Enseñat P, Muela F (March 2004). “The designer drug situation in Ibiza.” Published in “Forensic Science International,” 140(2–3), 195–206.

- Dams R, De Letter EA, Mortier KA, Cordonnier JA, Lambert WE, Piette MH, et al. (July 1, 2003). “Fatality due to combined use of the designer drugs MDMA and PMA: a distribution study.” Published in “Journal of Analytical Toxicology,” 27(5), 318–322.

- Caldicott DG, Edwards NA, Kruys A, Kirkbride KP, Sims DN, Byard RW, et al. (2003). “Dancing with ‘death’: p-methoxyamphetamine overdose and its acute management.” Published in “Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology,” 41(2), 143–154.

- Menon MK, Tseng LF, Loh HH (May 1976). “Pharmacological evidence for the central serotonergic effects of monomethoxyamphetamines.” Published in “The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics,” 197(2), 272–279.

- Hitzemann RJ, Loh HH, Domino EF (October 1971). “Effect of para-methoxyamphetamine on catecholamine metabolism in the mouse brain.” Published in “Life Sciences,” Pt. 1, 10(19), 1087–1095.

- Tseng LF, Menon MK, Loh HH (May 1976). “Comparative actions of monomethoxyamphetamines on the release and uptake of biogenic amines in brain tissue.” Published in “The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics,” 197(2), 263–271.

- Daws LC, Irvine RJ, Callaghan PD, Toop NP, White JM, Bochner F (August 2000). “Differential behavioural and neurochemical effects of para-methoxyamphetamine and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine in the rat.” Published in “Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry,” 24(6), 955–977.

- Green AL, El Hait MA (April 1980). “p-Methoxyamphetamine, a potent reversible inhibitor of type-A monoamine oxidase in vitro and in vivo.” Published in “The Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology,” 32(4), 262–266.

- Ask AL, Fagervall I, Ross SB (September 1983). “Selective inhibition of monoamine oxidase in monoaminergic neurons in the rat brain.” Published in “Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology,” 324(2), 79–87.

- Jaehne EJ, Salem A, Irvine RJ (July 2005). “Effects of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine and related amphetamines on autonomic and behavioral thermoregulation.” Published in “Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior,” 81(3), 485–496.

- Callaghan PD, Irvine RJ, Daws LC (October 2005). “Differences in the in vivo dynamics of neurotransmitter release and serotonin uptake after acute para-methoxyamphetamine and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine revealed by chronoamperometry.” Published in “Neurochemistry International,” 47(5), 350–361.

- Jaehne EJ, Salem A, Irvine RJ (September 2007). “Pharmacological and behavioral determinants of cocaine, methamphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, and para-methoxyamphetamine-induced hyperthermia.” Published in “Psychopharmacology,” 194(1), 41–52.

- Refstad S (November 2003). “Paramethoxyamphetamine (PMA) poisoning; a ‘party drug’ with lethal effects.” Published in “Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica,” 47(10), 1298–1299.

- Felgate HE, Felgate PD, James RA, Sims DN, Vozzo DC (March 1, 1998). “Recent paramethoxyamphetamine deaths.” Published in “Journal of Analytical Toxicology,” 22(2), 169–172.

- Galloway JH, Forrest AR (September 2002). “Caveat Emptor: Death involving the use of 4-methoxyamphetamine.” Published in “Journal of Clinical Forensic Medicine,” 9(3), 160.

- Lamberth PG, Ding GK, Nurmi LA (April 2008). “Fatal paramethoxy-amphetamine (PMA) poisoning in the Australian Capital Territory.” Published in “The Medical Journal of Australia,” 188(7), 426.

- “Renewed warning over ‘Rolex’ pills.” BBC News. July 24, 2013.

- “WATCH OUT FOR DANGEROUS SUPERMAN PILL – News – Deep House Amsterdam.” deephouseamsterdam.com. January 30, 2014.

- “¿Qué es Superman, la droga que ya ha cobrado varias vidas en el mundo?” [What is Superman, the drug that has already claimed several lives in the world?]. ElPais [The Country] (in Spanish). April 18, 2016.

- “Las claves para entender qué pasó.” La Nación. April 17, 2016.

- “Drug Warning – Reagent Tests UK.” www.reagent-tests.uk.

- “Annual Estimates Of Requirements Of Narcotic Drugs, Manufacture Of Synthetic Drugs, Opium Production And Cultivation Of The…” (PDF).

- Poisons Standard October 2015 https://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/F2015L01534

- “Valtioneuvoston asetus huumausaineina pidettävistä aineista, valmisteista ja kasveista annetun valtioneuvoston asetuksen muuttamisesta” [Decree of the Government on amending the government decree on substances, preparations and plants considered to be narcotic drugs]. Finlex (in Finnish). Helsinki: Finland’s Ministry of Justice. October 25, 2018.

- “Valtioneuvoston asetus huumausaineina pidettävistä aineista, valmisteista ja kasveista annetun valtioneuvoston asetuksen muuttamisesta” [Decree of the Government on amending the government decree on substances, preparations and plants considered to be narcotic drugs]. Finlex (in Finnish). Helsinki: Finland’s Ministry of Justice. January 13, 2022.

- “Doden na gebruik speed met 4-MA” [Deaths after using speed 4-MA] (in Dutch). June 13, 2012.

- 21 CFR 1308.11.

- Galloway JH, Forrest AR (September 2002). “Caveat Emptor: Death involving the use of 4-methoxyamphetamine.” Published in “Journal of Clinical Forensic Medicine,” 9(3), 160.

- “Drug Info.” Archived from the original on May 29, 2008.

- “Warning: pills sold as ecstasy found to contain PMA.”

- Chamberlin T, Murray D. NET Syndicated QLD News ‘Louis Vuitton’ designer death drug hits the streets.

- Kraner JC, McCoy DJ, Evans MA, Evans LE, Sweeney BJ (October 2001). “Fatalities caused by the MDMA-related drug paramethoxyamphetamine (PMA).” Published in “Journal of Analytical Toxicology,” 25(7), 645–648.