Contents

Summary

Clonidine, marketed under various trade names such as Catapres, Kapvay, Nexiclon, Clophelin, and more, is categorized as a depressant belonging to the imidazoline class of substances. While its primary application is in managing high blood pressure, it is versatile and can be employed for various medical conditions. These include attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, anxiety disorders, tic disorders, substance withdrawal, migraines, diarrhoea, and certain pain conditions.

Initially developed by Boehringer Ingelheim for its blood pressure-lowering properties, clonidine debuted in clinical practice in 1966. It marked a significant milestone as the first anti-hypertensive agent with a well-defined central mechanism of action, aiding in exploring central α-adrenoceptors’ role in regulating central blood pressure.

Clonidine is categorized as a centrally acting α2 adrenergic agonist and an imidazoline receptor agonist. Its influence on α2 receptors within the brainstem results in the inhibition of norepinephrine (NE) release, reducing sympathetic nervous system activity.

In addition to its approved uses, clonidine finds application in various off-label scenarios. Healthcare professionals may prescribe it for psychiatric conditions like stress, sleep disorders, and heightened arousal associated with post-traumatic stress disorder, borderline personality disorder, and other anxiety disorders.

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name | |

| CAS Number | 4205-90-7 |

|---|---|

| PubChem CID | 2803 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 516 |

| DrugBank | DB00575 |

| ChemSpider | 2701 |

| UNII | MN3L5RMN02 |

| KEGG | D00281 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:3757 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL134 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID6022846 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.021.928 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C9H9Cl2N3 |

| Molar mass | 230.09 g·mol−1 |

History and culture

During the early 1960s, the pharmaceutical scientist Helmut Stähle was assigned the task by Boehringer Ingelheim to create a peripherally active α-adrenergic compound for nasal decongestion through simple nasal drops. The aim was to develop a locally acting α-adrenergic vasoconstrictor that could alleviate the common cold symptoms by reducing the swelling of nasal membranes and facilitating unobstructed airflow.

The synthetic blueprint for clonidine materialized when Stähle conceived the notion of substituting two chlorine groups on the phenyl component of the imidazoline structure, which was the basis for most contemporary decongestive agents. At that juncture, incorporating a double halogen substitution into pharmaceuticals was still an uncommon practice, with the prevalent belief that compounds bearing multiple halogen atoms would, at best, serve as pesticides. Nonetheless, clonidine was pursued, and it was soon revealed to possess an exceptionally potent vasoconstrictive and decongestive effect, even at remarkably low doses.

The decongestive properties were subsequently verified through experiments conducted on the nasal cavities of anaesthetized dogs. However, after the inaugural human trials, it became evident that clonidine’s decongestant attributes were overshadowed by its remarkable antihypertensive effects. Consequently, the compound was repurposed for this newfound application and was introduced into clinical practice in 1966 under the trade name Catapres, gaining widespread use.

The discovery of clonidine played a pivotal role in bringing central α-adrenergic receptors to the attention of chemists, pharmacologists, and physicians. It became an indispensable pharmacological tool in elucidating the role of central α-adrenoceptors in central blood pressure regulation and the functioning of the nervous system.

In the 2010s, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved clonidine, either as a standalone treatment or in combination with stimulants, for managing attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in both pediatric and adult patients. Although clonidine is acknowledged in Australia, it does not hold official approval for use in ADHD by the TGA.

Chemistry

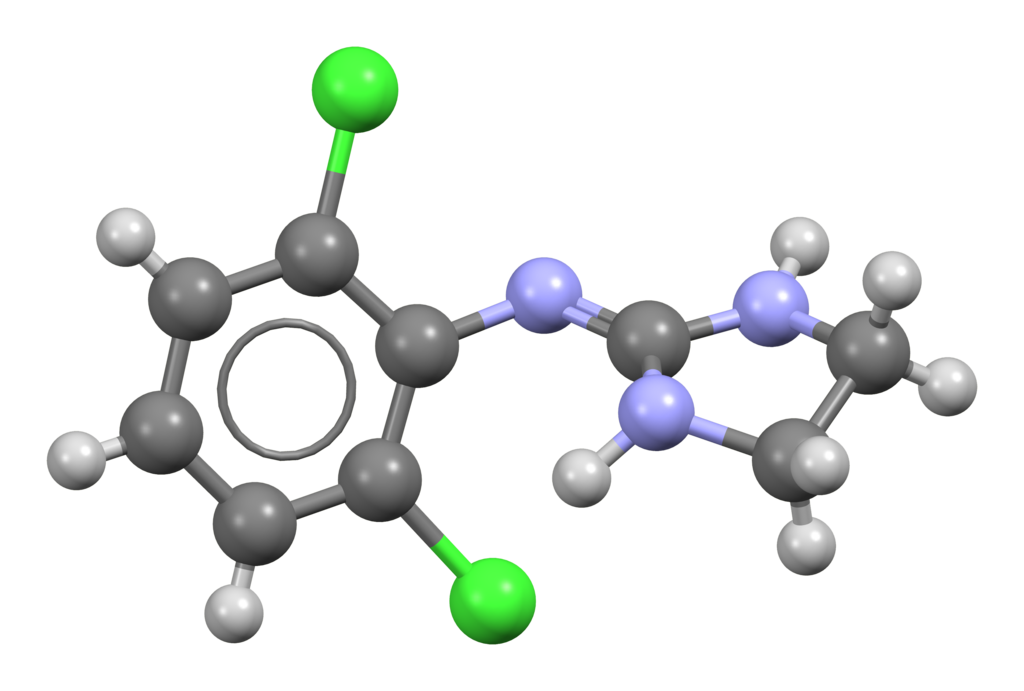

Clonidine, chemically known as 2-[(2,6-Dichlorophenyl)imino]imidazoline, belongs to the imidazoline chemical class, characterized by substituted amidines with the amidine function integrated into an imidazoline ring. This structural element is connected to an aromatic core through a methylene bridge.

Furthermore, two chlorine atoms are introduced at the 2- and 6-positions of the phenyl ring. This addition is pivotal in enhancing the molecule’s lipophilicity, allowing it to cross the blood-brain barrier effectively. In this chemical class, you can find other compounds like the α-adrenergic agents tolazoline, naphazoline, and phentolamine. The α-adrenergic effects of clonidine and its imidazolidine counterparts can be elucidated by recognizing a structural similarity between clonidine and norepinephrine.

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Clonidine acts as an agonist for the α2 adrenergic receptor. When these α2 receptors within the brain are activated, it reduces peripheral vascular resistance, subsequently causing a decrease in blood pressure. Clonidine exhibits a particular affinity for the presynaptic α2 receptors in the vasomotor centre within the brainstem. Upon binding to these receptors, it results in the reduction of presynaptic calcium levels and inhibition of norepinephrine (NE) release. The overall outcome is a decline in sympathetic nervous system activity.

There are three distinct G-protein coupled α2-receptor subtypes: α2A, α2B, and α2C. Each subtype exhibits a unique distribution pattern within the central nervous system and peripheral tissues. α2A receptors are widely distributed throughout the central nervous system, including regions such as the locus coeruleus, various brain stem nuclei, cerebral cortex, septum, hypothalamus, and hippocampus. Additionally, α2A receptors are found in peripheral tissues like the kidneys, spleen, thymus, lungs, and salivary glands. In contrast, the α2C receptor is predominantly expressed within the central nervous system, encompassing areas like the striatum, olfactory tubercle, hippocampus, and cerebral cortex. The α2B receptor, on the other hand, is primarily situated in peripheral tissues, including the kidney, liver, lung, and heart.[citation needed]

Both α2A and α2C receptors are located presynaptically and play a role in inhibiting the release of noradrenaline from sympathetic nerves. Activation of these receptors reduces sympathetic activity, resulting in lowered blood pressure and heart rate. Centrally located α2A receptors mediate sedation and analgesia, while peripheral α2B receptors are responsible for the constriction of vascular smooth muscle. α2A receptors also contribute to essential aspects of the analgesic effects of nitrous oxide in the spinal cord. Clonidine exhibits a similar potency in stimulating all three α2 receptor subtypes.

Moreover, clonidine possesses peripheral α1 agonist activity.

Additionally, clonidine acts as an agonist for the imidazoline I1 receptor, which is believed to underlie its antihypertensive effects.

| Binding Sites | Binding Affinity Ki (nM)[17] |

|---|---|

| α1A | 316.23 |

| α1B | 316.23 |

| α1D | 125.89 |

| α2A | 42.92 |

| α2B | 106.31 |

| α2C | 233.1 |

Subjective effects

Disclaimer: The following effects are sourced from the Subjective Effect Index (SEI), a research literature based on anecdotal user reports and the personal assessments of PsychonautWiki contributors. It is advisable to approach these effects with a degree of scepticism.

It’s important to note that these effects may not consistently manifest predictably, and their occurrence can vary. Higher doses are more likely to elicit the complete range of products but also increase the likelihood of adverse outcomes, including addiction, severe injury, or even death ☠.

Physical:

- Sedation: Clonidine can induce a potent sedative effect, often likened to the sedation caused by benzodiazepines. Users may become exceedingly tired and may sleep through attempts to awaken them.

- Decreased Heart Rate: Whether used in a standard or overdose scenario, clonidine lowers heart rate, and the extent of this effect correlates with dosage.

- Decreased Blood Pressure: Clonidine’s sympatholytic properties rapidly and efficiently reduce blood pressure. Users should exercise caution when transitioning from sitting to standing to avoid sudden lightheadedness or potential fainting spells.

- Abnormal Heartbeat: This effect is relatively rare, but warrants caution when clonidine is combined with substances that affect heart rhythm. Vigorous physical activity should be avoided while using this substance.

- Dry Mouth: Users may experience dryness in the mouth.

- Constipation: Clonidine use can lead to constipation.

- Physical Fatigue: A sense of physical fatigue may be encountered.

- Pupil Constriction: Clonidine can cause constriction of the pupils.

- Dizziness: Users may experience dizziness, increasing the risk of falls and injuries.

- Raynaud’s Phenomenon: This occurs due to arterial spasms, reducing blood flow to the extremities. Symptoms include pale skin, tingling, coldness, and numbness.

Cognitive:

- Cognitive Fatigue: Clonidine may induce mental fatigue.

- Addiction Suppression: Clonidine has effectively treated alcohol, opioid, and nicotine substance use disorders. It can also alleviate opiate withdrawal symptoms.

- Anxiety Suppression: Clonidine exhibits mild to moderate anxiolytic effects and is occasionally used clinically to address anxiety.

- Focus Enhancement: Typically observed at lower doses, clonidine can enhance focus, which is sometimes employed in treating ADHD.

- Focus Suppression: Higher doses of clonidine may result in a suppression of focus.

- Memory Enhancement: Some users report memory enhancement as an effect.

- Thought Deceleration: Clonidine can slow down thought processes.

Auditory:

- Auditory Suppression: Described as a “hollow” loss of hearing, this effect is attributed to reduced blood pressure.

After:

- Irritability: Users may experience heightened agitation and annoyance, particularly when discontinuing the medication abruptly. It is advised to taper off clonidine gradually rather than sudden cessation.

- Increased Heart Rate: Following prolonged use, an increased heart rate may manifest as a rebound effect of clonidine’s antihypertensive actions.

- Increased Blood Pressure: Similarly, a rebound effect to clonidine’s antihypertensive properties may lead to an elevation in blood pressure, especially with sustained use.

Toxicity

At Therapeutic Doses

In the typical therapeutic dosage range of 0.2-0.9 mg/day, clonidine is commonly associated with several adverse effects, including dry mouth, sedation, dizziness, and constipation. While generally considered safe within therapeutic limits, clonidine can pose significant risks at toxic doses, potentially leading to severe cardiopulmonary instability and central nervous system (CNS) depression in children and adults. Caution is advised when combining clonidine with other depressant substances.

It is strongly recommended to practice harm reduction when using clonidine.

Lethal Dosage

The oral LD50 (lethal dose for 50% of the population) for clonidine is approximately 206 mg/kg in mice and 465 mg/kg in rats. However, human lethality is rare, with only a few reported fatalities. Notably, cardiorespiratory and CNS dysfunction morbidity tends to be more severe in young individuals than adults.

Overdose

Signs of clonidine overdose include constricted pupils, drowsiness, initially high blood pressure followed by a drop in pressure, irritability, lowered body temperature, slowed breathing, reduced heart rate, delayed reflexes, and weakness.

Some case reports suggest that naloxone may be a potential antidote for clonidine overdoses, although this remains relatively uncommon in clinical practice.

Tolerance and Addiction Potential

Clonidine is not considered addictive and carries a low risk of abuse. However, chronic clonidine use can lead to physical dependence, and sudden discontinuation may result in withdrawal symptoms, including rebound hypertension. Gradual tapering is generally recommended to prevent this complication.

While not inherently addictive, instances of misuse have been documented, particularly among individuals with pre-existing substance use disorders. Sometimes, clonidine is used with opioids to enhance and prolong their effects, potentially elevating the risk of oversedation and respiratory depression associated with opioid use.

Dangerous Interactions Warning:

Many psychoactive substances that are typically safe when used alone can become hazardous or even life-threatening when combined with specific other substances. The following list outlines some known dangerous interactions (though it may not encompass all potential risks).

It is crucial to conduct independent research (e.g., using Google, DuckDuckGo, or PubMed) to confirm the safety of combining two or more substances. Some of these interactions have been sourced from TripSit.

- Depressants (e.g., 1,4-Butanediol, 2M2B, alcohol, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, GHB/GBL, methaqualone, opioids): Combining these substances can amplify muscle relaxation, amnesia, sedation, and respiratory depression. At higher doses, there is an increased risk of sudden loss of consciousness and dangerously decreased respiration. Additionally, unconscious individuals may be at risk of suffocating from vomit.

- Dissociatives: Combining dissociatives and depressants can unpredictably enhance amnesia, sedation, loss of motor control, and delusions. It may also lead to sudden loss of consciousness and significant respiratory depression. If nausea or vomiting occurs before losing consciousness, it is advisable to try to fall asleep in the recovery position or have someone assist with this.

- Stimulants: Stimulants can mask the sedative effects of depressants, making it challenging for users to gauge their level of intoxication accurately. When the stimulating effects wear off, the impact of the depressant can markedly intensify, leading to increased disinhibition, loss of motor control, and potentially dangerous blackout episodes. This combination can also raise the risk of severe dehydration if fluid intake is not carefully monitored. If choosing to combine these substances, strict limits on Dosage and timing are essential to avoid adverse outcomes.

Legal status

Germany: Clonidine is categorized as prescription medicine, as per Anlage 1 AMVV.

Switzerland: Clonidine is classified under “Abgabekategorie B” pharmaceuticals, necessitating a prescription for acquisition.

United States: Clonidine is exclusively obtainable with a valid prescription.

FAQ

- What is Clonidine, and what is it used for?

- Clonidine is a medication belonging to the class of alpha-2 adrenergic agonists. It primarily treats conditions like high blood pressure (hypertension). However, it can also be prescribed for other states, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety disorders, and substance withdrawal symptoms.

- How does Clonidine work?

- Clonidine works by stimulating alpha-2 receptors in the brain. This stimulation leads to a decrease in peripheral vascular resistance, resulting in lowered blood pressure. It also decreases the release of norepinephrine, reducing sympathetic nervous system activity.

- What are the common side effects of Clonidine?

- Common side effects of Clonidine can include dry mouth, sedation, dizziness, constipation, and decreased heart rate. It’s essential to discuss any side effects with your healthcare provider.

- Is Clonidine addictive?

- Clonidine itself is not considered addictive. However, physical dependence can develop with chronic use. Following your healthcare provider’s instructions when discontinuing Clonidine is essential to avoid withdrawal symptoms.

- Are there any dangerous interactions with Clonidine?

- Yes, Clonidine can interact with various substances, including depressants, dissociatives, and stimulants. Combining Clonidine with certain substances can lead to dangerous respiratory depression and other adverse effects. Always consult a healthcare professional or research to ensure the safety of combining Clonidine with other substances.

- What should I do in case of a Clonidine overdose?

- Symptoms of a Clonidine overdose may include pupil constriction, drowsiness, and high blood pressure, followed by a drop in anxiety, irritability, and slowed breathing. Seek immediate medical attention if you suspect an overdose. Naloxone may be used as an antidote in some cases.

- Is Clonidine available without a prescription?

- No, Clonidine is not available without a prescription in most countries. It is a prescription medication, and you should only use it under the guidance of a qualified healthcare provider.

- Can Clonidine be used for anxiety or ADHD treatment?

- Clonidine is sometimes prescribed for anxiety disorders due to its mild to moderate anxiolytic (anxiety-reducing) effects. It is also used to treat ADHD, particularly at lower doses.

- How should I taper off Clonidine if I need to stop taking it?

- To avoid rebound hypertension and other withdrawal symptoms, it’s crucial to taper off Clonidine gradually under the supervision of your healthcare provider. Do not discontinue use suddenly.

- Is Clonidine safe during pregnancy and breastfeeding?

- Clonidine use during pregnancy and breastfeeding should be discussed with a healthcare provider. They can weigh the potential benefits against the risks and provide guidance based on your situation.

References

- Soni, H., Brayfield, A., eds. (13 January 2014). “Exploring Clonidine in “Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference”. Published by Pharmaceutical Press. Volume 22, Issue 5, Pages 12–12. doi:10.7748/en.22.5.12.s13. ISSN 1354-5752. Retrieved on 28 June 2014.

- Stähle, H. (June 2000). “A Journey through the Development of Clonidine” in “Best Practice & Research Clinical Anaesthesiology”. Volume 14, Issue 2, Pages 237–246. doi:10.1053/bean.2000.0079. ISSN 1521-6896.

- Neil, M. J. (November 2011). “Clonidine: Unveiling Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutic Use in Pain Management” from “Current Clinical Pharmacology”. Volume 6, Issue 4, Pages 280–287. doi:10.2174/157488411798375886. ISSN 2212-3938.

- Shen, Howard (2008). “Illustrated Pharmacology Memory Cards: PharMnemonics”. Minireview, Page 12. ISBN 1-59541-101-1.

- van der Kolk, BA (September–October 1987). “The Medication Approach to Treating Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder” in “Journal of Affective Disorders”. Volume 13, Issue 2, Pages 203–213. doi:10.1016/0165-0327(87)90024-3. PMID 2960712.

- Sutherland, SM; Davidson, JR (June 1994). “Pharmacotherapy for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder” from “The Psychiatric Clinics of North America”. Volume 17, Issue 2, Pages 409–423. PMID 7937367.

- Southwick, SM; Bremner, JD; Rasmusson, A; Morgan CA, 3rd; Arnsten, A; Charney, DS (November 1999). “Role of Norepinephrine in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Insights from Research” in “Biological Psychiatry”. Volume 46, Issue 9, Pages 1192–1204. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(99)00219-X. PMID 10560025.

- Strawn, JR; Geracioti, TD, Jr (2008). “Noradrenergic Dysfunction and the Psychopharmacology of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder” as presented in “Depression and Anxiety”. Volume 25, Issue 3, Pages 260–271. doi:10.1002/da.20292. PMID 17354267.

- Boehnlein, JK; Kinzie, JD (March 2007). “Pharmacologic Reduction of CNS Noradrenergic Activity in PTSD: The Role of Clonidine and Prazosin” from “Journal of Psychiatric Practice”. Volume 13, Issue 2, Pages 72–78. doi:10.1097/01.pra.0000265763.79753.c1. PMID 17414682.

- Huffman, JC; Stern, TA (2007). “Exploring Neuropsychiatric Consequences of Cardiovascular Medications” in “Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience”. Volume 9, Issue 1, Pages 29–45. PMC 3181843 Freely accessible. PMID 17506224.

- Najjar, F; Weller, RA; Weisbrot, J; Weller, EB (April 2008). “Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and its Treatment in Children and Adolescents” as discussed in “Current Psychiatry Reports”. Volume 10, Issue 2, Pages 104–108. doi:10.1007/s11920-008-0019-0. PMID 18474199.

- Ziegenhorn, AA; Roepke, S; Schommer, NC; Merkl, A; Danker-Hopfe, H; Perschel, FH; Heuser, I; Anghelescu, IG; Lammers, CH (April 2009). “Clonidine’s Role in Improving Hyperarousal in Borderline Personality Disorder with or without Comorbid Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Evidence from a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial” as presented in “Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology”. Volume 29, Issue 2, Pages 170–173. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e31819a4bae. PMID 19512980.

- Rossi, S., Australasian Society of Clinical and Experimental Pharmacologists and Toxicologists, Pharmaceutical Society of Australia, Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (2013). “Australian Medicines Handbook 2013”. Published by Australian Medicines Handbook. ISBN 9780980579093.

- Sullivan, P. A., De Quattro, V., Foti, A., Curzon, G. (July 1986). “Effects of Clonidine on Central and Peripheral Nerve Tone in Primary Hypertension” discussed in “Hypertension”. Volume 8, Issue 7, Pages 611–617. doi:10.1161/01.hyp.8.7.611. ISSN 0194-911X.

- Bricca, G., Greney, H., Zhang, J., Dontenwill, M., Stutzmann, J., Belcourt, A., Bousquet, P. (January 1994). “Exploring Human Brain Imidazoline Receptors with [3H]Clonidine” in “European Journal of Pharmacology: Molecular Pharmacology”. Volume 266, Issue 1, Pages 25–33. doi:10.1016/0922-4106(94)90205-4. ISSN 0922-4106.

- Reis, D. J., Piletz, J. E. (November 1997). “The Imidazoline Receptor and its Control of Blood Pressure through Clonidine and Allied Drugs” as covered in “The American Journal of Physiology”. Volume 273, Issue 5, Pages R1569–1571. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.5.R1569. ISSN 0002-9513.

- Roth, BL; Driscol, J (12 January 2011). “PDSP Ki Database”. Accessible through Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP), University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Archived from the original on 8 November 2013. Retrieved on 25 November 2013.

- Anderson, R. J., Hart, G. R., Crumpler, C. P., Lerman, M. J. (February 1981). “Clonidine Overdose: Report of Six Cases and Review of the Literature” from “Annals of Emergency Medicine”. Volume 10, Issue 2, Pages 107–112. doi:10.1016/s0196-0644(81)80350-2. ISSN 0196-0644.

- Mitchell, A., Bührmann, S., Opazo Saez, A., Rushentsova, U., Schäfers, R. F., Philipp, T., Nürnberger, J. (January 2005). “Clonidine’s Effects on Blood Pressure Reduction by Modifying Vascular Resistance and Cardiac Output in Young, Healthy Males” discussed in “Cardiovascular Drugs and Therapy”. Volume 19, Issue 1, Pages 49–55. doi:10.1007/s10557-005-6890-6. ISSN 0920-3206.

- Gold, Mark S., Redmond, D. E., Kleber, Herbert D. (September 1978). “Clonidine’s Role in Mitigating Acute Opiate Withdrawal Symptoms” as documented in “The Lancet”. Volume 312, Issue 8090, Pages 599–602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(78)92823-4. ISSN 0140-6736.

- Hoehn-Saric, R. (1 November 1981). “Effects of Clonidine on Anxiety Disorders” covered in “Archives of General Psychiatry”. Volume 38, Issue 11, Page 1278. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780360094011. ISSN 0003-990X.

- Niemann, J. T., Getzug, T., Murphy, W. (October 1986). “Reversal of Clonidine Toxicity by Naloxone” in “Annals of Emergency Medicine”. Volume 15, Issue 10, Pages 1229–1231. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(86)80874-5. ISSN 0196-0644.

- Dennison, S. J. (2001). “Clonidine’s Misuse among Opiate Addicts” discussed in “The Psychiatric Quarterly”. Volume 72, Issue 2, Pages 191–195. doi:10.1023/a:1010375727768. ISSN 0033-2720.

- “AMVV – Verordnung über die Verschreibungspflicht von Arzneimitteln.”

- “CLONIDINE HYDROCHLORIDE TABLETS, USP Rx only.”