Contents

Summary

Tramadol, which goes by the brand names Ultram, Ralivia, or Tramal, is classified as a synthetic opioid in the phenylpropylamine category. It shares structural similarities with codeine and morphine. Its primary actions include acting as a weak agonist at the μ-opioid receptors and inhibiting the reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin.

Initially developed in 1962, Tramadol was introduced to the market as “Tramal” by the German pharmaceutical company Grünenthal GmbH in 1977. Subsequently, in the mid-1990s, it gained approval for use in the United Kingdom and the United States. Physicians frequently prescribe it to manage moderate to moderately severe pain.

The subjective effects of Tramadol closely resemble those of traditional opioids. These effects encompass sedation, pain alleviation, anxiety reduction, muscle relaxation, and a sense of euphoria. Additionally, Tramadol produces mild to moderate entactogenic effects, such as an increased appreciation of music, enhanced empathy, affection, and sociability. These effects are believed to arise from its serotonergic properties.

Distinct from other opioids, Tramadol has been associated with reducing the seizure threshold in humans and elevating the risk of serotonin syndrome. Consequently, its effects and interactions can be relatively unpredictable. Therefore, using high Tramadol or combining it with other psychoactive substances is strongly discouraged.

When considering Tramadol, it is strongly recommended to implement harm reduction practices to minimize potential risks and adverse effects associated with its consumption.

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name | |

| CAS Number | 27203-92-5 |

|---|---|

| PubChem CID | 33741 |

| DrugBank | DB00193 |

| ChemSpider | 31105 |

| UNII | 39J1LGJ30J |

| KEGG | D08623 as HCl: D01355 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:9648 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL1066 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID90858931 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.043.912 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C16H25NO2 |

| Molar mass | 263.381 g·mol−1 |

History and culture

Tramadol was synthesized in 1962 by scientists employed by the German pharmaceutical company Grünenthal. However, it did not receive approval in Germany until 1977, when it was introduced to the market as Tramal. Over the past 38 years, it has gained acceptance in more than 100 countries, including the UK, USA, Republic of China, and Canada, establishing itself as the leading analgesic medication in Germany.

For a time, there was a misconception that tramadol might not be entirely synthetic, as it was thought to have been discovered in the roots of the pin cushion tree. However, subsequent investigations revealed that these reports were incorrect. The presence of tramadol in the hearts was traced back to cows that had been treated with the drug, leading to its excretion in their urine, which in turn seeped into the hearts of the tree.

Chemistry

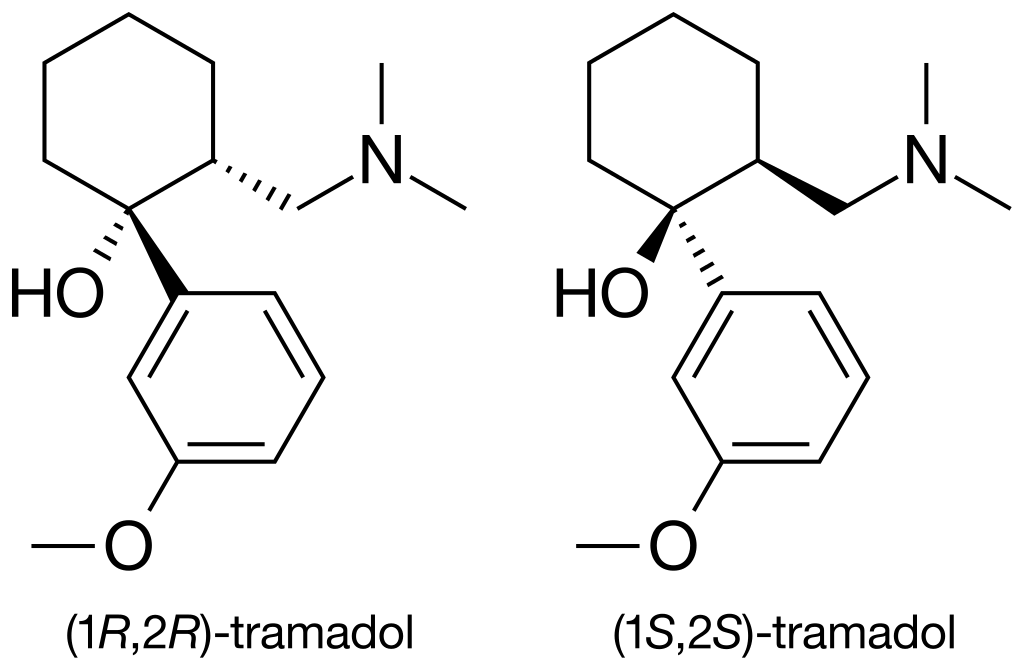

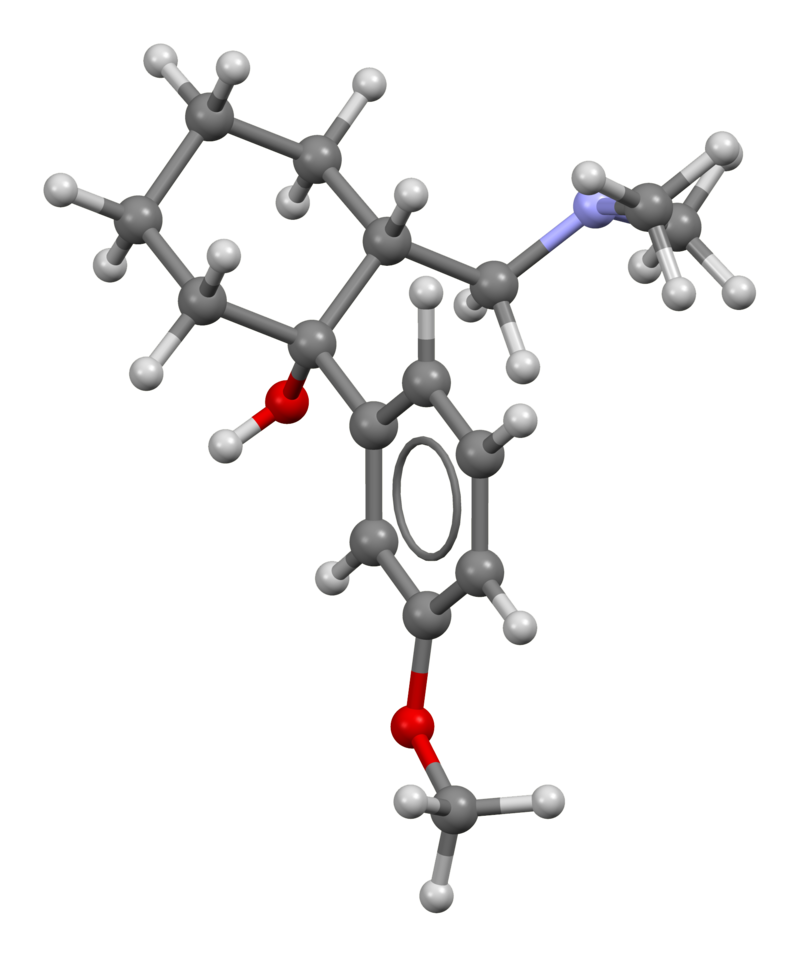

Tramadol, also known by its chemical name 2-[(Dimethylamino)methyl]-1-(3-methoxyphenyl)cyclohexanol, is an unconventional synthetic opioid. Its chemical structure comprises two interconnected rings: a cyclohexane ring bonded to a phenyl ring at R1. At R3 of the phenyl ring, there is a methoxy group (CH3O-), and at the exact location (R1), the cyclohexane ring is connected to an additional hydroxy group. Tramadol exhibits another substitution on its cyclohexane ring at R2, linked to a dimethylamine group via a methyl bridge.

What sets Tramadol apart is its existence as a racemate, a combination of its stereoisomers. These stereoisomers are two molecules with identical chemical structures but differing three-dimensional arrangements. Tramadol is produced as a racemate of these two isomers because this combination is more effective. The image displayed above depicts the R-enantiomer of Tramadol, and inverting the dashed and solid wedges on the molecular skeleton results in the S-enantiomer. Tramadol is typically manufactured as a hydrochloride salt.

Tramadol shares similarities with codeine, being a 4-phenylpiperidine analogue. Importantly, it is distinct from morphinan opiates.

Pharmacology

The R- and S-enantiomers of tramadol exert their actions on distinct receptors in a complementary fashion. The R-enantiomer selectively activates mu receptors and inhibits serotonin reuptake, while the S-enantiomer inhibits the reuptake of noradrenaline. Tramadol functions as an opioid receptor agonist, a serotonin-releasing agent, a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, an NMDA receptor antagonist, a 5-HT2C receptor antagonist, an (α7)5 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist, and an antagonist of M1 and M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors.

Tramadol undergoes a metabolic transformation into O-Desmethyltramadol (O-DSMT), considerably more potent as an opioid.

The euphoric effects of tramadol stem from its interaction with the μ-opioid receptor. This interaction occurs because opioids structurally mimic endogenous endorphins, naturally occurring in the body and activating the μ-opioid receptor. The structural resemblance of opioids to these natural endorphins leads to the experience of euphoria, pain relief, and anxiety reduction. Endorphins are responsible for diminishing pain, inducing drowsiness, and eliciting feelings of pleasure. They can be released in response to pain, vigorous physical activity, orgasm, or general excitement.

Subjective effects

Disclaimer: The effects outlined below are sourced from the Subjective Effect Index (SEI), a compilation of research literature and anecdotal user accounts analyzed by contributors to PsychonautWiki. It is advisable to approach these effects with a healthy dose of scepticism.

Recognizing that these effects may not manifest predictably or consistently is essential. However, higher doses are more likely to encompass the full range of products. Additionally, as quantities increase, the risk of adverse consequences such as addiction, severe injury, or even fatality ☠ becomes more significant.

Physical:

- Sedation & Stimulation: At lower to moderate doses, tramadol exhibits a notably more stimulating quality compared to conventional opiates like codeine and heroin, primarily due to its action as a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. Higher doses, on the other hand, are marked by sedation and lethargy, characteristic of traditional opiates.

- Pain Relief (citation needed)

- Physical Euphoria: Tramadol’s physical euphoria is perceived as less intense when compared to that of morphine or heroin. This sensation can be described as profound feelings of extreme physical comfort, warmth, love, and bliss.

- Itchiness: Tramadol tends to cause more pronounced itchiness than other opioids due to the higher histamine release.

- Constipation (citation needed)

- Cough Suppression (citation needed)

- Dehydration (citation needed): Tramadol can lead to significant dehydration, especially at higher doses. Users are advised to stay hydrated throughout the experience to mitigate the comedown and side effects like headaches.

- Difficulty Urinating

- Nausea (citation needed)

- Pupil Constriction (citation needed)

- Decreased Libido (citation needed)

- Appetite Suppression

- Orgasm Suppression (citation needed)

- Seizures (citation needed)

- Headaches seem to occur more frequently with tramadol than other opioids, although not everyone experiences them. The underlying cause remains unclear, though it may be linked to its SNRI (serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor) properties.

- Restless Legs

Cognitive:

- General Mental State: Tramadol is often described as inducing a mental state characterized by stimulation, euphoria, relaxation, anxiety reduction, and pain relief.

- Disinhibition

- Cognitive Euphoria: Tramadol’s mental euphoria is considered less intense than that of morphine or diacetylmorphine (heroin). It entails a potent and overwhelming sensation of emotional bliss, contentment, and happiness.

- Empathy, Affection, and Sociability Enhancement

- Anxiety Suppression

- Anxiety: While tramadol is more inclined to suppress anxiety, it can induce it under certain conditions. This effect might be attributed to the noradrenergic properties of the substance.

- Irritability: Opioids are known for mood improvement but can paradoxically heighten sensitivity to irritants, leading to aloofness and sudden outbursts of anger and aggression (commonly known as “opiate rage”). This seems to occur more frequently during the comedown or with heavy use, and tramadol’s noradrenergic properties may contribute to this effect.

- Thought Acceleration

- Compulsive Redosing

- Motivation Enhancement

- Dream Potentiation

- Increased Music Appreciation

- Wakefulness

Toxicity

Disclaimer: Tramadol exhibits low toxicity relative to its dose. However, like all opioids, long-term effects can vary, including reduced libido, apathy, and memory impairment. Tramadol can become potentially lethal when combined with depressants like alcohol or benzodiazepines. Furthermore, it possesses a broader range of substances that can be hazardous compared to other opioids. It is strongly cautioned against using tramadol during benzodiazepine withdrawals, as this combination may potentially trigger seizures.

It is highly recommended to practice harm reduction when using this substance.

Dependence and Abuse Potential

As with other opioids, chronic use of tramadol can lead to moderate addiction potential and a high likelihood of abuse, potentially causing psychological dependence in certain users. Once addiction sets in, cravings and withdrawal symptoms may occur if a person abruptly discontinues their usage.

Tolerance develops with prolonged and repeated tramadol use, but the rate of development varies for different effects. For instance, tolerance to the constipation-inducing effects develops slowly. Consequently, users may need increasingly larger doses to achieve the same impact. Patience typically takes 3 to 7 days to reduce by half and 1 to 2 weeks to return to baseline (without further consumption). Tramadol also presents cross-tolerance with all other opioids, meaning that after consuming tramadol, all opioids will have a diminished effect.

Dangerous Interactions

Warning: Several psychoactive substances that are reasonably safe when used independently can become dangerous and even life-threatening when combined with specific other substances. The list below highlights some known dangerous interactions, though it may not encompass all.

It is imperative to conduct independent research (e.g., Google, DuckDuckGo, PubMed) to ascertain the safety of consuming a combination of two or more substances. Some of the interactions listed have been sourced from TripSit.

- Amphetamines: Mixing tramadol with stimulants like amphetamines can lead to serotonin syndrome, as both substances impact monoamine neurotransmitters.

- Cocaine: Similar to amphetamines, combining tramadol with cocaine can result in serotonin syndrome due to their shared impact on monoamine neurotransmitters.

- DXM (Dextromethorphan): DXM has serotonin-releasing properties, and when combined with tramadol’s SNRI activity, it can cause serotonin syndrome.

- GHB/GBL: These substances can potentiate each other unpredictably, leading to rapid unconsciousness and the risk of vomit aspiration while unconscious.

- MAOIs (Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors): Co-administration with certain opioids has been linked to severe adverse reactions, including excitatory and depressive symptoms and, in some cases, death.

- Benzodiazepines: Combining tramadol with benzodiazepines can have an additive central nervous system and respiratory depressant effects, potentially leading to unconsciousness and memory blackouts.

- MXE: MXE can enhance opioid effects and heighten the risk of respiratory depression and organ toxicity.

- Alcohol: Both substances can amplify ataxia and sedation, possibly causing unexpected loss of consciousness, emphasizing the need to place affected individuals in the recovery position.

- Nitrous: Combined, they can potentiate ataxia and sedation, leading to sudden unconsciousness. Vomit aspiration is a risk while unconscious, and memory blackouts are common.

- Grapefruit: While not psychoactive, grapefruit can affect the metabolism of certain opioids, including tramadol, potentially leading to increased toxicity with repeated doses. It may also prolong the drug’s clearance from the body.

Serotonin Syndrome Risk

Combinations with the following substances can result in dangerously elevated serotonin levels, leading to serotonin syndrome, which requires immediate medical attention and can be fatal if left untreated:

- MAOIs include Syrian rue, banisteriopsis caapi, phenelzine, selegiline, and moclobemide.

- Serotonin releasers like MDMA, 4-FA, methamphetamine, methylone, and aMT.

- 2C-T-x

- DXM

Legal status

Austria: Tramadol is legally available for medical use under the AMG (Arzneimittelgesetz Österreich) but is prohibited when sold or possessed without a prescription, as stipulated by the SMG (Suchtmittelgesetz Österreich).

Malaysia: Tramadol is not categorized as a First Schedule drug in Malaysia’s Dangerous Drugs Act of 1952.

Germany: Tramadol is classified as a prescription medication, as outlined in Anlage 1 AMVV.

Sweden: As of May 2008, Sweden has designated tramadol as a controlled substance akin to codeine and dextropropoxyphene. This means that tramadol is a scheduled drug, although it can still be obtained with a regular prescription at this time.

Switzerland: Tramadol is classified as a pharmaceutical in “Abgabekategorie A,” requiring a prescription for acquisition.[citation needed]

Turkey: Tramadol is available solely by ‘green prescription’ and is illegal for sale or possession without a prescription.

United Kingdom: On June 10, 2014, tramadol was reclassified as a Class C drug under the Misuse of Drugs Act.

United States: Tramadol is categorized as a Schedule IV controlled substance in the United States.

FAQ

1. What is Tramadol?

- Tramadol is a synthetic opioid medication that relieves moderate to moderately severe pain. It works by acting on the brain’s opioid receptors and inhibiting the reuptake of certain neurotransmitters like serotonin and norepinephrine.

2. How is Tramadol typically prescribed?

- Tramadol is commonly prescribed in tablet or capsule form, and the dosage depends on the severity of the pain and the individual’s response to the medication. It is often taken every 4 to 6 hours for pain relief.

3. Is Tramadol safe to use?

- Tramadol is generally safe when used as prescribed by a healthcare professional. However, it can have side effects and potential risks, especially when misused or combined with other substances. It should only be taken under medical supervision.

4. What are the common side effects of Tramadol?

- Common side effects may include dizziness, drowsiness, nausea, constipation, headache, and dry mouth. It’s essential to report any unusual or severe side effects to your healthcare provider.

5. Is Tramadol addictive?

- Tramadol has the potential for addiction, especially with long-term use or when taken in higher doses than prescribed. It is classified as a Schedule IV controlled substance in the United States due to its addiction potential.

6. Can Tramadol be taken with other medications?

- Tramadol may interact with other drugs, especially those that affect serotonin levels, such as certain antidepressants. It’s crucial to inform your doctor about all medications, supplements, or herbal products to avoid potential interactions.

7. What precautions should be taken when using Tramadol?

- It’s essential to follow your doctor’s instructions carefully and not exceed the recommended dosage. Tramadol should not be mixed with alcohol or other central nervous system depressants, as it can increase the risk of respiratory depression and other adverse effects.

8. Is Tramadol safe during pregnancy and breastfeeding?

- Tramadol is generally not recommended during pregnancy or breastfeeding, as it can pass through breast milk and potentially harm the infant. Pregnant or breastfeeding individuals should consult with their healthcare provider for safer alternatives.

9. What should I do if I miss a dose of Tramadol?

- If you miss a dose, take it as soon as you remember. However, if it’s close to the next scheduled dose, skip the missed one and continue with your regular dosing schedule. Do not take extra doses to make up for the missed one.

10. Can Tramadol be stopped abruptly?

- Abruptly discontinuing Tramadol can lead to withdrawal symptoms. If you need to stop taking it, consult your doctor, who will typically recommend a gradual reduction in dosage to minimize withdrawal effects.

11. What should I do in case of an overdose?

- An overdose of Tramadol can be life-threatening. If you suspect an overdose or experience symptoms like difficulty breathing, extreme drowsiness, or seizures, seek immediate medical attention.

12. How can I safely dispose of unused Tramadol?

- To prevent misuse, follow local guidelines or ask your pharmacist for proper disposal methods for unused or expired Tramadol.

Please note that this FAQ is for informational purposes only and should not replace professional medical advice. Consult a healthcare provider for personalized guidance regarding Tramadol or any other medication.

References

- Klotz, U. (25 December 2011). “Tramadol — the Impact of its Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Properties on the Clinical Management of Pain”. Arzneimittelforschung. 53 (10): 681–687. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1299812. ISSN 0004-4172.

- Reimann, W., Schneider, F. (22 May 1998). “Induction of 5-hydroxytryptamine release by tramadol, fenfluramine, and reserpine”. European Journal of Pharmacology. 349 (2): 199–203. doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(98)00195-2. ISSN 0014-2999.

- Gobbi, M., Moia, M., Pirona, L., Ceglia, I., Reyes-Parada, M., Scorza, C., Mennini, T. (19 September 2002). “p-Methylthioamphetamine and 1-(m-chlorophenyl)piperazine, two non-neurotoxic 5-HT releasers in vivo, differ from neurotoxic amphetamine derivatives in their mode of action at 5-HT nerve endings in vitro: Effects of MTA and mCPP in synaptosomes”. Journal of Neurochemistry. 82 (6): 1435–1443. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01073.x. ISSN 0022-3042.

- Leppert, W. (November 2009). “Tramadol as an analgesic for mild to moderate cancer pain”. Pharmacological Reports. 61 (6): 978–992. doi:10.1016/S1734-1140(09)70159-8. ISSN 1734-1140.

- Talaie, H., Panahandeh, R., Fayaznouri, M. R., Asadi, Z., Abdollahi, M. (June 2009). “Dose-independent occurrence of seizure with tramadol”. Journal of Medical Toxicology. 5 (2): 63–67. doi:10.1007/BF03161089. ISSN 1556-9039.

- Lassen, D., Damkier, P., Brøsen, K. (August 2015). “The Pharmacogenetics of Tramadol”. Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 54 (8): 825–836. doi:10.1007/s40262-015-0268-0. ISSN 0312-5963.

- Boumendjel, A., Sotoing Taïwe, G., Ngo Bum, E., Chabrol, T., Beney, C., Sinniger, V., Haudecoeur, R., Marcourt, L., Challal, S., Ferreira Queiroz, E., Souard, F., Le Borgne, M., Lomberget, T., Depaulis, A., Lavaud, C., Robins, R., Wolfender, J.-L., Bonaz, B., De Waard, M. (4 November 2013). “Occurrence of the Synthetic Analgesic Tramadol in an African Medicinal Plant”. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 52 (45): 11780–11784. doi:10.1002/anie.201305697. ISSN 1433-7851.

- Kusari, S., Tatsimo, S. J. N., Zühlke, S., Talontsi, F. M., Kouam, S. F., Spiteller, M. (3 November 2014). “Tramadol-A True Natural Product?”. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 53 (45): 12073–12076. doi:10.1002/anie.201406639. ISSN 1433-7851.

- Dayer, P., Desmeules, J., Collart, L. (1997). “[Pharmacology of tramadol]”. Drugs. 53 Suppl 2: 18–24. doi:10.2165/00003495-199700532-00006. ISSN 0012-6667.

- Hennies, H. H., Friderichs, E., Schneider, J. (July 1988). “Receptor binding, analgesic and antitussive potency of tramadol and other selected opioids”. Arzneimittel-Forschung. 38 (7): 877–880. ISSN 0004-4172.

- Frink, M. C., Hennies, H. H., Englberger, W., Haurand, M., Wilffert, B. (November 1996). “Influence of tramadol on neurotransmitter systems of the rat brain”. Arzneimittel-Forschung. 46 (11): 1029–1036. ISSN 0004-4172.

- Driessen, B., Reimann, W. (January 1992). “Interaction of the central analgesic, tramadol, with the uptake and release of 5-hydroxytryptamine in the rat brain in vitro”. British Journal of Pharmacology. 105 (1): 147–151. ISSN 0007-1188.

- Bamigbade, T. A., Davidson, C., Langford, R. M., Stamford, J. A. (September 1997). “Actions of tramadol, its enantiomers, and principal metabolite, O-desmethyltramadol, on serotonin (5-HT) efflux and uptake in the rat dorsal raphe nucleus”. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 79 (3): 352–356. doi:10.1093/bja/79.3.352. ISSN 0007-0912.

- Hara, K., Minami, K., Sata, T. (May 2005). “The Effects of Tramadol and Its Metabolite on Glycine, γ-Aminobutyric AcidA, and N-Methyl-d-Aspartate Receptors Expressed in Xenopus Oocytes:”. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 100 (5): 1400–1405. doi:10.1213/01.ANE.0000150961.24747.98. ISSN 0003-2999.

- Ogata, J., Minami, K., Uezono, Y., Okamoto, T., Shiraishi, M., Shigematsu, A., Ueta, Y. (May 2004). “The Inhibitory Effects of Tramadol on 5-Hydroxytryptamine Type 2C Receptors Expressed in Xenopus Oocytes:”. Anesthesia & Analgesia: 1401–1406. doi:10.1213/01.ANE.0000108963.77623.A4. ISSN 0003-2999.

- Shiraishi, M., Minami, K., Uezono, Y., Yanagihara, N., Shigematsu, A. (October 2001). “Inhibition by tramadol of muscarinic receptor-induced responses in cultured adrenal medullary cells and in Xenopus laevis oocytes expressing cloned M1 receptors”. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 299 (1): 255–260. ISSN 0022-3565.

- Shiga, Y., Minami, K., Shiraishi, M., Uezono, Y., Murasaki, O., Kaibara, M., Shigematsu, A. (November 2002). “The Inhibitory Effects of Tramadol on Muscarinic Receptor-Induced Responses in Xenopus Oocytes Expressing Cloned M3 Receptors”. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 95 (5): 1269–1273. doi:10.1097/00000539-200211000-00031. ISSN 0003-2999.

- Hoque, R., Chesson, A. L. (15 February 2010). “Pharmacologically induced/exacerbated restless legs syndrome, periodic limb movements of sleep, and REM behavior disorder/REM sleep without atonia: literature review, qualitative scoring, and comparative analysis”. Journal of clinical sleep medicine: JCSM: official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 6 (1): 79–83. ISSN 1550-9389.

- Gillman, P. K. (October 2005). “Monoamine oxidase inhibitors, opioid analgesics, and serotonin toxicity”. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 95 (4): 434–441. doi:10.1093/bja/aei210. ISSN 0007-0912.

- First Schedule Drugs Dangerous Drugs Act 1952 and Regulations

- AMVV – Verordnung über die Verschreibungspflicht von Arzneimitteln

- Tramadol Classification in Sweden – http://www.lakemedelsverket.se/Alla-nyheter/NYHETER-2008/Substansen-tramadol-nu-narkotikaklassad-pa-samma-satt-som-kodein-och-dextropropoxifen/

- Tramadol Classification in Turkey – YEŞİL REÇETEYE TABİ İLAÇLAR | https://www.titck.gov.tr/storage/Archive/2019/contentFile/01.04.2019%20SKRS%20Ye%C5%9F%C4%B1l%20Re%C3%A7eteli%20%C4%B0la%C3%A7lar%20Aktif%20SON%20-%20G%C3%9CNCEL_58b1ff4a-2e1c-4867-bad7-eec855d6162a.pdf

- The Misuse of Drugs Act in the United Kingdom – https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2014/1106/made

- DEA Controlled Drugs in the United States – https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/schedules/orangebook/e_cs_sched.pdf