Contents

Summary

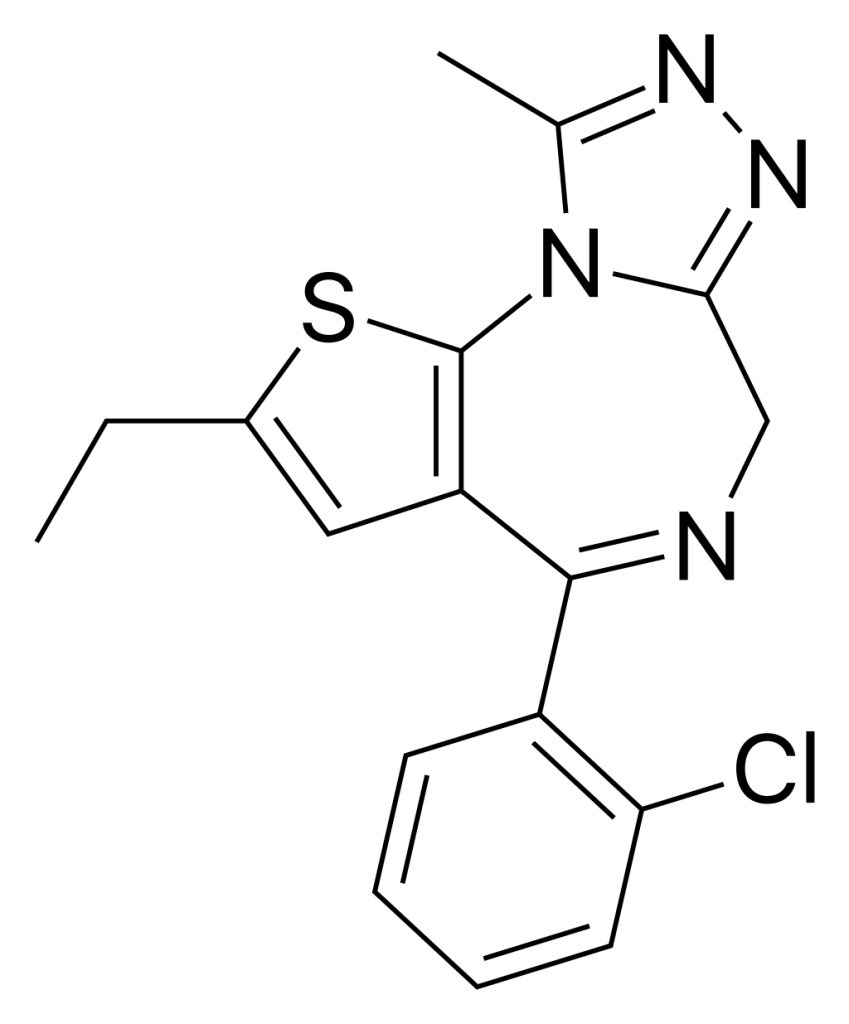

Etizolam, available under numerous brand names, is a derivative of thienodiazepine, essentially an analogue of benzodiazepine. It distinguishes itself by substituting the benzene ring with a thiophene ring and fusing a triazole ring, effectively categorizing it as a thienotriazolodiazepine.

Although categorized as a thienodiazepine, Etizolam is clinically treated as a benzodiazepine due to its mechanism of action via the benzodiazepine receptor, which directly interacts with GABAA allosteric modulator receptors.

Etizolam exhibits a range of properties, including anxiolysis, amnesic effects, anticonvulsant action, hypnotic qualities, sedation, and muscle relaxant capabilities.

This compound was patented in 1972 and received approval for medical use in 1983.

As of April 2021, the export of Etizolam has been prohibited in India.

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name | |

| CAS Number | 40054-69-1 |

|---|---|

| PubChem CID | 3307 |

| ChemSpider | 3191 |

| UNII | A76XI0HL37 |

| KEGG | D01514 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL1289779 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID0023030 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.188.773 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C17H15ClN4S |

| Molar mass | 342.85 g·mol−1 |

Side effects

- Prolonged use may result in the occurrence of blepharospasms, particularly among female individuals.

- Doses exceeding 4 mg may induce anterograde amnesia.

In rare instances, the appearance of erythema annulare centrifugum skin lesions has been reported.

Tolerance, Dependence, and Withdrawal:

Abrupt or swift discontinuation of etizolam, akin to benzodiazepines, can precipitate the onset of benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome, which includes rebound insomnia. It is worth noting that neuroleptic malignant syndrome, a rare occurrence in benzodiazepine withdrawal, has been documented in a case of sudden etizolam withdrawal. This is particularly relevant due to etizolam’s comparatively short half-life in comparison to benzodiazepines such as diazepam, resulting in a more rapid reduction of drug levels in blood plasma.

In a study comparing the effectiveness of etizolam, alprazolam, and bromazepam in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder, all three drugs exhibited effectiveness over 2 weeks. Notably, etizolam’s effectiveness increased from 2 to 4 weeks. Administration of 0.5 mg etizolam twice daily for 3 weeks did not result in cognitive deficits when compared to a placebo.

When multiple doses of etizolam or lorazepam were administered to rat neurons, lorazepam led to the downregulation of alpha-1 benzodiazepine binding sites (indicative of tolerance and dependence). In contrast, etizolam caused an increase in alpha-2 benzodiazepine binding sites, signifying reverse tolerance to anti-anxiety effects. Tolerance to the anticonvulsant effects of lorazepam was observed, but no significant tolerance to the anticonvulsant effects of etizolam was detected. As a result, etizolam exhibits a reduced tendency to induce tolerance and dependence in comparison to traditional benzodiazepines. It is considered a possible anxiolytic choice with a reduced likelihood of producing tolerance and dependence following long-term treatment for anxiety and stress syndromes.

Pharmacology

Etizolam, a derivative of thienodiazepine, is absorbed rather swiftly, with peak plasma levels attained within 30 minutes to 2 hours. It boasts potent hypnotic properties and is on par with other short-acting benzodiazepines. Etizolam functions as a positive allosteric modulator of the GABAA receptor by binding to the receptor’s benzodiazepine site.

According to Italian prescribing information, etizolam belongs to a new class of diazepines known as thienotriazolodiazepines. This class is characterized by easy oxidation, rapid metabolism, and a lower risk of accumulation even after extended treatment. Etizolam’s anxiolytic effect is approximately 6-8 times greater than that of diazepam. It notably reduces the time taken to fall asleep, increases total sleep duration, and reduces the number of awakenings. While there are no significant changes in deep sleep, it may decrease REM sleep. In EEG tests involving healthy volunteers, etizolam exhibited characteristics akin to tricyclic antidepressants.

The primary metabolites of etizolam in humans are alpha-hydroxyetizolam and 8-hydroxyetizolam. Alpha-hydroxyetizolam is pharmacologically active and has a half-life of roughly 8.2 hours.

Interactions:

Itraconazole and fluvoxamine slow down the elimination rate of etizolam, leading to its accumulation and enhanced pharmacological effects. In contrast, carbamazepine accelerates etizolam metabolism, reducing its pharmacological effects.

Overdose

Cases of intentional suicide by overdose involving etizolam in combination with GABA agonists have been reported. While etizolam has a lower LD50 than certain benzodiazepines, it still significantly exceeds the prescribed or recommended dose. Flumazenil, a GABA antagonist used to counter benzodiazepine overdoses, counteracts the effects of etizolam, much like with classical benzodiazepines such as diazepam and chlordiazepoxide. Etizolam overdose deaths are on the rise, with “street” etizolam being implicated in a significant number of drug-related deaths.

Society and Culture:

Brand Names:

Etilaam, Sedekopan, Etizest, Etizex, Pasaden, or Depas

Legal Status:

International drug control conventions: While it was initially suggested in 1990 that etizolam should not be subject to international control, this stance has shifted due to increased abuse. In December 2019, the World Health Organization recommended placing etizolam in Schedule 4 of the 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances, a recommendation that was enacted in March 2020.

Australia: Etizolam is not used medically but has been found in counterfeit Xanax pills.

Denmark: Etizolam is controlled in Denmark under the Danish Misuse of Drugs Act.

Germany: Although controlled in Germany since July 2013, it is not used medically.

Italy: Etizolam is a prescription-only medication used for the treatment of anxiety, insomnia, and neurosis.

India: In India, it is a prescription-only medication used for anxiety disorders, sometimes in combination with other drugs like propranolol.

United Kingdom: Etizolam is classified as a Class C drug in the UK as of the May 2017 amendment to The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971, alongside several other designer benzodiazepine drugs.

United States: Etizolam is not authorized by the FDA for medical use. As of March 2016, it is a controlled substance in various states and was placed under temporary Schedule I status by the DEA in 2023.

Misuse:

Etizolam is a substance at risk of misuse, with cases of dependence documented in the medical literature. Misuse and addiction have significantly increased since 1991, primarily due to varying accessibility and cultural popularity. Illicitly manufactured pills sold as Xanax or other benzodiazepines may often contain etizolam rather than their listed ingredient.

FAQ

- What is Etizolam?

- Etizolam is a thienodiazepine derivative, often used as an anxiolytic or to manage anxiety and sleep disorders. It is similar in action to benzodiazepines but belongs to a distinct chemical class called thienotriazolodiazepines.

- How does Etizolam work?

- Etizolam functions as a positive allosteric modulator of the GABAA receptor by targeting the receptor’s benzodiazepine site. This interaction contributes to its anxiolytic and sedative effects.

- What are the common brand names for Etizolam?

- Etizolam is marketed under various brand names, including Etilaam, Sedekopan, Etizest, Etizex, Pasadena, and Depas.

- Is Etizolam legally available?

- The legal status of Etizolam varies by country. In some places, it is available as a prescription-only medication, while in others, it is classified as a controlled substance. It is essential to check your local regulations.

- What are the potential effects of Etizolam?

- Etizolam possesses anxiolytic, amnesic, anticonvulsant, hypnotic, sedative, and muscle relaxant properties. These effects can vary depending on the dosage and individual factors.

- Can Etizolam lead to dependence or tolerance?

- While Etizolam shares similarities with benzodiazepines, some studies suggest it may have a reduced potential for inducing tolerance and dependence compared to traditional benzodiazepines.

- What is the recommended dosage of Etizolam?

- The appropriate dosage of Etizolam can vary based on an individual’s condition and response to the drug. It is crucial to follow medical advice and not exceed prescribed dosages.

- Are there any potential side effects of Etizolam?

- Common side effects may include drowsiness, dizziness, and impaired coordination. Rarely, skin lesions or more severe side effects can occur. Always consult a healthcare professional for guidance.

- Can Etizolam be abused or misused?

- Yes, Etizolam has been subject to misuse and abuse, leading to cases of dependence and addiction. It is crucial to use it as prescribed and under the guidance of a healthcare provider.

- Is it safe to combine Etizolam with other substances or medications?

- Combining Etizolam with other drugs or substances, including alcohol, can be dangerous and may lead to adverse effects or interactions. Always consult a healthcare professional before combining medications or substances.

- Is Etizolam available over the counter (OTC)?

- No, Etizolam typically requires a prescription for legal use. In many regions, it is not available over the counter.

- Is Etizolam banned in any country?

- The legal status of Etizolam varies by country. Some countries have banned or controlled its use due to concerns about misuse and abuse.

- What is the future of Etizolam’s legal status?

- The legal status of Etizolam may change over time. It’s essential to stay updated with local regulations and any updates from health authorities.

References

- **Anvisa (2023-03-31). “RDC Nº 784 – Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial” [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 – Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 2023-04-04). Archived from the original on 2023-08-03. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- **”Etizolam”. www.drugbank.ca. Retrieved 2020-09-03.

- **”Drug & Chemical Evaluation – Etizolam” (PDF). U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. U.S. Department of Justice. March 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-09-03.

- **Fracasso C, Confalonieri S, Garattini S, Caccia S (1991-02-01). “Single and multiple dose pharmacokinetics of etizolam in healthy subjects”. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 40 (2): 181–185. doi:10.1007/BF00280074. PMID 2065698. S2CID 10176681.

- **Sanna E, Pau D, Tuveri F, Massa F, Maciocco E, Acquas C, et al. (February 1999). “Molecular and neurochemical evaluation of the effects of etizolam on GABAA receptors under normal and stress conditions”. Arzneimittel-Forschung. 49 (2): 88–95. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1300366. PMID 10083975. S2CID 19732765.

- **Manchester KR, Maskell PD, Waters L (March 2018). “Experimental versus theoretical log D7.4, pKa and plasma protein binding values for benzodiazepines appearing as new psychoactive substances” (PDF). Drug Testing and Analysis. 10 (8): 1258–1269. doi:10.1002/dta.2387. PMID 29582576.

- **Niwa T, Shiraga T, Ishii I, Kagayama A, Takagi A (September 2005). “Contribution of human hepatic cytochrome p450 isoforms to the metabolism of psychotropic drugs”. Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 28 (9): 1711–6. doi:10.1248/bpb.28.1711. PMID 16141545.

- **Catabay A, Taniguchi M, Jinno K, Pesek JJ, Williamsen E (1 March 1998). “Separation of 1,4-Benzodiazepines and Analogues Using Cholesteryl-10-Undecenoate Bonded Phase in Microcolumn Liquid Chromatography”. Journal of Chromatographic Science. 36 (3): 111–118. doi:10.1093/chromsci/36.3.111.

- **Mandrioli R, Mercolini L, Raggi MA (October 2008). “Benzodiazepine metabolism: an analytical perspective”. Current Drug Metabolism. 9 (8): 827–844. doi:10.2174/138920008786049258. PMID 18855614.

- **US 3904641, “Triazolothienodiazepine compounds”

- **Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 536. ISBN 9783527607495.

- **”EGazette Home”.[dead link]

- **Lopedota A, Cutrignelli A, Trapani A, Boghetich G, Denora N, Laquintana V, et al. (May 2007). “Effects of different cyclodextrins on the morphology, loading and release properties of poly (DL-lactide-co-glycolide)-microparticles containing the hypnotic agent etizolam”. Journal of Microencapsulation. 24 (3): 214–24. doi:10.1080/02652040601058152. PMID 17454433. S2CID 31434550.

- **Wakakura M, Tsubouchi T, Inouye J (March 2004). “Etizolam and benzodiazepine induced blepharospasm”. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 75 (3): 506–507. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2003.019869. PMC 1738986. PMID 14966178.

- **Kuroda K, Yabunami H, Hisanaga Y (January 2002). “Etizolam-induced superficial erythema annulare centrifugum”. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 27 (1): 34–6. doi:10.1046/j.0307-6938.2001.00943.x. PMID 11952667. S2CID 36251540.

- **Hirase M, Ishida T, Kamei C (November 2008). “Rebound insomnia induced by abrupt withdrawal of hypnotics in sleep-disturbed rats”. European Journal of Pharmacology. 597 (1–3): 46–50. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.08.024. PMID 18789918.

- **Kawajiri M, Ohyagi Y, Furuya H, Araki T, Inoue N, Esaki S, et al. (February 2002). “[A patient with Parkinson’s disease complicated by hypothyroidism who developed malignant syndrome after discontinuation of etizolam]” [A patient with Parkinson’s disease complicated by hypothyroidism who developed malignant syndrome after discontinuation of etizolam]. Rinsho Shinkeigaku = Clinical Neurology (in Japanese). 42 (2): 136–9. PMID 12424963.

- **Greenblatt DJ (February 1985). “Elimination half-life of drugs: value and limitations”. Annual Review of Medicine. 36 (1): 421–7. doi:10.1146/annurev.me.36.020185.002225. PMID 3994325.

- **Bertolino A, Mastucci E, Porro V, Corfiati L, Palermo M, Ecari U, Ceccarelli G (25 June 2016). “Etizolam in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a controlled clinical trial”. The Journal of International Medical Research. 17 (5): 455–60. doi:10.1177/030006058901700507. PMID 2572494. S2CID 43179840.

- **De Candia MP, Di Sciascio G, Durbano F, Mencacci C, Rubiera M, Aguglia E, et al. (December 2009). “Effects of treatment with etizolam 0.5 mg BID on cognitive performance: a 3-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, two-treatment, three-period, noninferiority crossover study in patients with anxiety disorder”. Clinical Therapeutics. 31 (12): 2851–9. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.12.010. PMID 20110024.

- **Sanna E, Busonero F, Talani G, Mostallino MC, Mura ML, Pisu MG, et al. (September 2005). “Low tolerance and dependence liabilities of etizolam: molecular, functional, and pharmacological correlates”. European Journal of Pharmacology. 519 (1–2): 31–42. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.06.047. PMID 16107249.

- **Sanna E, Busonero F, Talani G, Mostallino MC, Mura ML, Pisu MG, et al. (September 2005). “Low tolerance and dependence liabilities of etizolam: molecular, functional, and pharmacological correlates”. European Journal of Pharmacology. 519 (1–2): 31–42. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.06.047. PMID 16107249.

- **Nakamura J, Mukamae H (December 1992). “Effects of thienodiazepine derivatives, etizolam and clotiazepam on the appearance of Fm theta”. The Japanese Journal of Psychiatry and Neurology. 46 (4): 927–31. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.1992.tb02862.x. PMID 1363923. S2CID 11263866.

- **Yakushiji T, Fukuda T, Oyama Y, Akaike N (November 1989). “Effects of benzodiazepines and non-benzodiazepine compounds on the GABA-induced response in frog isolated sensory neurones”. British Journal of Pharmacology. 98 (3): 735–40. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb14600.x. PMC 1854765. PMID 2574062.

- **”Depas”. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- **”Etizolam”. PubChem. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 2020-09-03.

- **Nakamae T, Shinozuka T, Sasaki C, Ogamo A, Murakami-Hashimoto C, Irie W, et al. (November 2008). “Case report: Etizolam and its major metabolites in two unnatural death cases”. Forensic Science International. 182 (1–3): e1-6. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2008.08.012. PMID 18976871.

- **Araki K, Yasui-Furukori N, Fukasawa T, Aoshima T, Suzuki A, Inoue Y, et al. (August 2004). “Inhibition of the metabolism of etizolam by itraconazole in humans: evidence for the involvement of CYP3A4 in etizolam metabolism”. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 60 (6): 427–30. doi:10.1007/s00228-004-0789-1. PMID 15232663. S2CID 22970567.

- **Suzuki Y, Kawashima Y, Shioiri T, Someya T (December 2004). “Effects of concomitant fluvoxamine on the plasma concentration of etizolam in Japanese psychiatric patients: wide interindividual variation in the drug interaction”. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 26 (6): 638–42. doi:10.1097/00007691-200412000-00009. PMID 15570188. S2CID 12164244.

- **Kondo S, Fukasawa T, Yasui-Furukori N, Aoshima T, Suzuki A, Inoue Y, et al. (May 2005). “Induction of the metabolism of etizolam by carbamazepine in humans”. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 61 (3): 185–8. doi:10.1007/s00228-005-0904-y. PMID 15776275. S2CID 9612361.

- **Høiseth G, Tuv SS, Karinen R (November 2016). “Blood concentrations of new designer benzodiazepines in forensic cases”. Forensic Science International. 268: 35–38. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2016.09.006. PMID 27685473.

- **Woolverton WL, Nader MA (December 1995). “Effects of several benzodiazepines, alone and in combination with flumazenil, in rhesus monkeys trained to discriminate pentobarbital from saline”. Psychopharmacology. 122 (3): 230–6. doi:10.1007/bf02246544. PMID 8748392. S2CID 24836734.

- **”Drug-related deaths in Scotland 2018″ (PDF). National Records of Scotland.

- **”Expert Committee on Drug Dependence’s Twenty Seventh Report” (PDF). World Health Organization. September 28, 1990. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- **”Letter of WHO Director-General to UN Secretary-General dated November 15th 2019″ (PDF). www.who.int.

- **”News: Recently scheduled benzodiazepines Flualprazolam and Etizolam associated with multiple post-mortem and DUID cases in UNODC EWA”. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. March 2020.

- **”Warnings over counterfeit benzodiazepines”. NSW Health.

- **”Bekendtgørelse om euforiserende stoffer”. retsinformation.dk (in Danish). Retrieved 2016-11-21.

- **”Verordnungsentwurf der Bundesregierung” [Federal draft regulation] (PDF). Bundesministerium für Gesundheit (Federal Ministry of Health) (in German). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 March 2016.

- **”Gesetz über den Verkehr mit Betäubungsmitteln” [Law on traffic with tranquillizers]. Bundesministerium der Justiz und für Verbraucherschutz (Federal Ministry of Justice and Consumer Protection) (in German).

- **”DEPAS – Etizolam”. 2017-08-31. Retrieved 2018-05-14.

- **PubChem. “Etizolam”. pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2021-03-06.

- **”The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (Amendment) Order 2017″.

- **”Alabama Code Title 20. Food, Drugs, and Cosmetics § 20-2-23″. Findlaw.

- **”List of Controlled Substances” (PDF). State of Arkansas. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2011.

- **”Statutes & Constitution: Online Sunshine”. www.leg.state.fl.us.

- **”HB1231 (As Sent to Governor) – 2014 Regular Session”. billstatus.ls.state.ms.us.

- **”Health and Safety Code Chapter 481. Texas Controlled Substances Act”. statutes.capitol.texas.gov. Retrieved 2019-07-12.

- **”Controlled Substance Schedule | SCDHEC”. www.scdhec.gov. Retrieved 2019-03-20.

- **”18VAC110-20-322. Placement of Chemicals in Schedule I”. Commonwealth of Virginia. 2 December 2015. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- **”Ellington’s bill banning two deadly drugs could soon be law – State of Indiana House of Representatives”. www.indianahouserepublicans.com.

- **”(Proposed Rule) Schedules of Controlled Substances: Temporary Placement of Etizolam, Flualprazolam, Clonazolam, Flubromazolam, and Diclazepam in Schedule I”. Federal Register. DEA. December 23, 2022.

- **”Schedules of Controlled Substances: Temporary Placement of Etizolam, Flualprazolam, Clonazolam, Flubromazolam, and Diclazepam in Schedule I” (PDF). Federal Register. DEA. July 25, 2023. Retrieved 2023-07-25.

- **Gupta S, Garg B (2014). “A case of etizolam dependence”. Indian Journal of Pharmacology. 46 (6): 655–6. doi:10.4103/0253-7613.144943. PMC 4264086. PMID 25538342.

- **Allison D (20 April 2018). “How to tackle Dundee’s fake valium epidemic”. BBC News.

- **Guirguis A. “Novel psychoactive substances: understanding the new illegal drug market”. Pharmaceutical Journal.

- **”Drug Data Xanax”. DrugData.org. Retrieved 9 April 2020.