Contents

Summary

Fentanyl, known by various brand names such as Sublimaze, Actiq, Durogesic, and others, belongs to the anilidopiperidine class of potent opioid substances. It acts as a strong agonist at μ-opioid receptors and is approximately 40 to 50 times more powerful than pure heroin and roughly 80 to 100 times more potent than morphine.

Pharmaceutical fentanyl is available in various forms, including transdermal skin patches, lollipops, buccal tablets or patches, nasal sprays, and inhalers. On the illicit market, it is often encountered in powder form, where it may be mixed with or sold as other drugs like heroin, leading to a significant number of accidental overdoses and fatalities. In fact, in 2016, fentanyl and its analogs became the leading cause of overdose deaths in the United States, contributing to over 20,000 fatalities, constituting approximately half of all opioid-related deaths.

The subjective effects of fentanyl are similar to those of heroin and include pain relief (analgesia), sedation, respiratory depression, and euphoria. However, fentanyl has a rapid onset and relatively short duration of action compared to other opioids, potentially leading to compulsive redosing. Many users also report experiencing less euphoria with fentanyl and its analogs, making it generally less appealing for recreational use.

Fentanyl is a highly hazardous substance due to its high addictiveness and the challenges associated with safe dosing because of its remarkable potency. Users are strongly advised to recognize the immense risks associated with its use. Additionally, users must employ reagent testing kits to check all opioids and substances for the presence of fentanyl and other potential contaminants to ensure their safety.

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name | |

| CAS Number | 437-38-7 |

|---|---|

| PubChem CID | 3345 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 1626 |

| DrugBank | DB00813 |

| ChemSpider | 3228 |

| UNII | UF599785JZ |

| KEGG | D00320 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:119915 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL596 |

| PDB ligand | 7V7 (PDBe, RCSB PDB) |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID9023049 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.468 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C22H28N2O |

| Molar mass | 336.479 g·mol−1 |

History and culture

Fentanyl, initially synthesized by Paul Janssen in 1960, emerged following the earlier development of pethidine for medical use. Janssen’s work involved the assessment of analogs of the structurally related compound pethidine to identify their opioid activity. This research led to the creation of fentanyl.

The introduction of fentanyl into clinical practice paved the way for the production of fentanyl citrate, which entered the medical field as a general anesthetic under the trade name Sublimaze during the 1960s. Subsequently, numerous other fentanyl analogs were developed and incorporated into medical applications, including sufentanil, alfentanil, remifentanil, and carfentanil.

In the mid-1990s, fentanyl gained widespread use for palliative care with the introduction of the Duragesic patch. Over the next decade, quick-acting prescription forms of fentanyl intended for personal use were introduced, such as the Actiq lollipop and Fentora buccal tablets, delivered through the innovative method of estradiol Mylan transdermal patches.

As of 2012, fentanyl had become the most extensively utilized synthetic opioid in clinical settings. Furthermore, various new delivery methods have since become available, including a sublingual spray designed to assist cancer patients. In 2013, a total of 1,700 kilograms of fentanyl were utilized on a global scale.

Chemistry

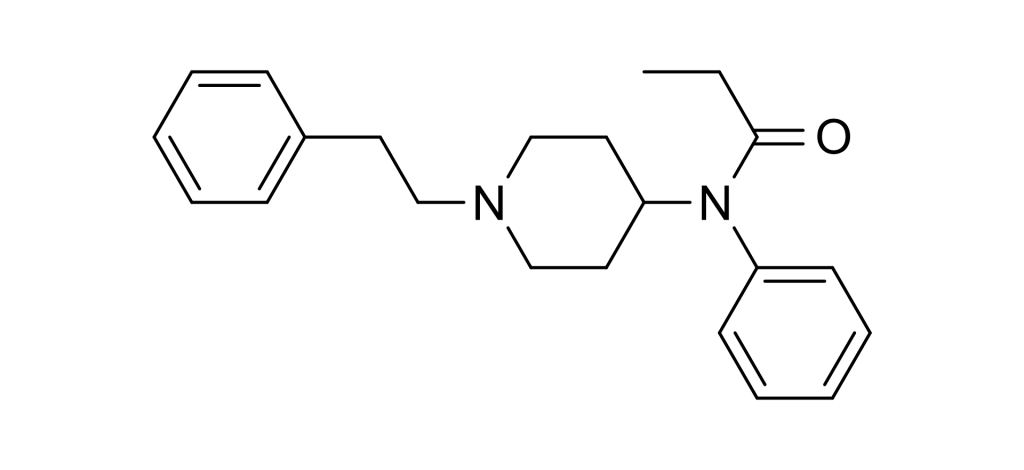

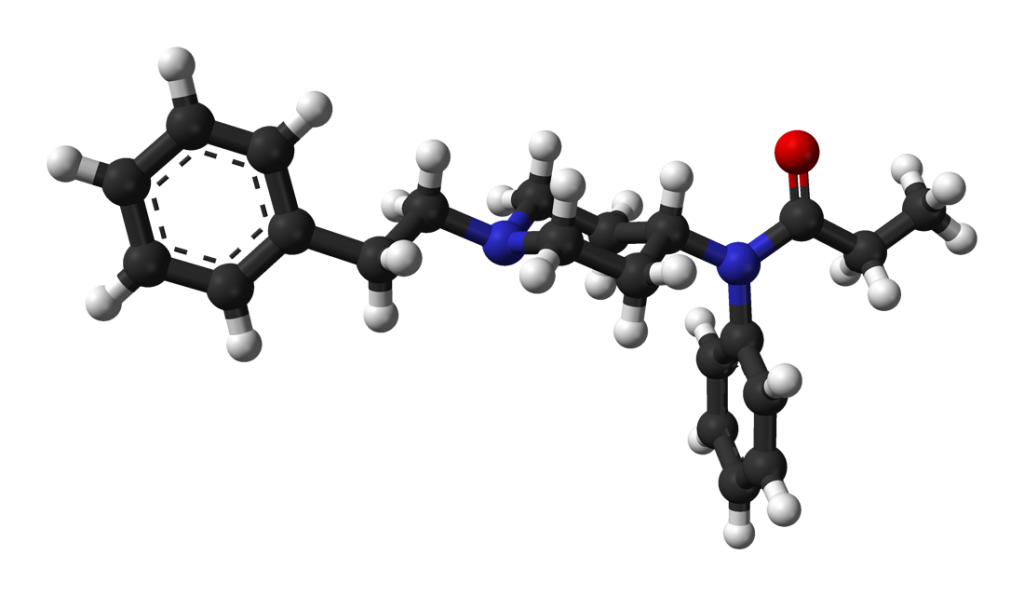

Fentanyl belongs to the synthetic opioids known as the anilidopiperidine class. Its chemical structure comprises a piperidine ring, which is connected at its nitrogen atom (RN) to a phenyl ring via an ethyl chain. On the other side of the piperidine ring, there is a propanamide group attached, consisting of a three-carbon chain with a nitrogen atom adjacent to a carbon atom bonded to an oxygen atom in a ketone group. Additionally, this propanamide group is further substituted with an extra phenyl ring at the RN position.

Pharmacology

The recreational effects of fentanyl stem from its structural resemblance to endogenous endorphins, which naturally occur in the body and interact with the μ-opioid receptor system. Opioids mimic these natural endorphins, leading to sensations of euphoria, pain relief, and reduced anxiety. Endorphins are responsible for diminishing pain, inducing drowsiness, and eliciting feelings of pleasure. They are released in response to various stimuli, including pain, vigorous physical activity, orgasm, or moments of excitement.

Fentanyl’s remarkable potency, exceeding that of morphine, can be primarily attributed to its high lipophilicity, signifying its ability to dissolve in fats, oils, and lipids readily. This property enables it to more effectively permeate the central nervous system when compared to other opioids.

Subjective effects

Disclaimer: The effects described below are based on anecdotal user reports and the insights of contributors to the Subjective Effect Index (SEI) at PsychonautWiki. It’s essential to approach these descriptions with a healthy dose of skepticism.

Please note that individual experiences can vary, and the effects of fentanyl may not occur predictably or reliably, with higher doses increasing the likelihood of experiencing the full range of products. It’s crucial to be aware that higher doses may also lead to adverse effects, including addiction, severe harm, or even death ☠.

Physical

Sedation: Fentanyl is known for its pronounced sedative properties, often causing significant drowsiness and fatigue even at moderate dosages. This sedation can be more profound than that of heroin or oxycodone. Pain Relief – Fentanyl is a potent analgesic, providing relief from pain even at non-recreational doses. Physical Euphoria – While less intense than morphine or heroin, fentanyl can induce strong feelings of material comfort, warmth, and bliss throughout the body. Itchiness – Fentanyl tends to cause minimal itchiness compared to other opioids, mainly due to the low histamine release associated with it. Respiratory Depression – Fentanyl exhibits respiratory depression effects at lower doses relative to euphoria compared to other opioids. Even at low doses, it may mildly to moderately slow down breathing, but it typically doesn’t cause noticeable impairment. At high doses and overdoses, opioid-induced respiratory depression can lead to shortness of breath, abnormal breathing patterns, semi-consciousness, or unconsciousness. Severe overdoses can result in coma or death without prompt medical intervention. Constipation Cough Suppression Decreased Libido Difficulty Urinating Pupil Constriction Increased Perspiration Decreased Blood Pressure Appetite Suppression Orgasm Suppression

Cognitive

Cognitive Euphoria: Fentanyl’s mental euphoria is considered less intense than that of morphine or heroin due to limitations in the conversion of the drug into its active form through metabolism. Nonetheless, it can still induce extreme intensity and overwhelming bliss at higher doses with low tolerance. This sensation involves a decisive and overwhelming feeling of emotional joy, contentment, and happiness. Anxiety Suppression Compulsive Redosing Dream Potentiation

Visual

Suppressions Double Vision: At high doses, fentanyl can cause uncontrollable eye focus and refocus, resulting in blurred vision and double vision that persists regardless of where one directs one’s gaze.

Toxicity

Fentanyl use, especially for non-medical purposes and by individuals without opioid tolerance, can be hazardous and has resulted in numerous fatalities. Even individuals with opioid tolerance are at a heightened risk of overdosing. Once fentanyl enters the user’s system, it becomes challenging to halt its effects due to its rapid absorption. Given its exceptionally high potency in pure powder form, proper dilution is difficult to achieve, often resulting in mixtures that are too potent and, consequently, highly dangerous. Combining fentanyl with depressants like alcohol or benzodiazepines can also be potentially lethal.

Similar to most opioids, the primary long-term concerns associated with fentanyl use are dependence and constipation. Harmful or toxic consequences of opioid use typically result from insufficient precautions regarding administration, overdose, or the use of impure substances.

Fentanyl possesses an extraordinary potency, approximately 1000 times more absorbent than morphine. Although fentanyl absorption through the skin is relatively slow, inadvertently transferring the substance from the skin to the mouth, nose, or eyes can be hazardous.

Heavy doses of fentanyl can lead to respiratory depression, potentially resulting in fatal or hazardous oxygen deprivation. This occurs because fentanyl suppresses the breathing reflex in a dose-dependent manner.

Fentanyl can also induce nausea and vomiting, and a substantial number of opioid overdose deaths are attributed to unconscious victims aspirating on their vomit. This can be prevented by ensuring that individuals lie on their sides with their heads tilted downward, preventing airway blockage in case of unconscious vomiting (known as the recovery position). In case of an overdose, it is advisable to administer naloxone intravenously or intramuscularly to counteract the effects of the substance.

It is strongly recommended that harm reduction practices be employed when using this substance.

Tolerance and Addiction Potential

Like other opioids, fentanyl’s chronic use is highly addictive and carries a substantial risk of abuse, leading to both psychological and physical dependence. If individuals suddenly cease usage, cravings and withdrawal symptoms may occur.

Tolerance to various fentanyl effects develops with prolonged and repeated use. The rate of tolerance development differs for different products, with constipation-inducing effects developing particularly slowly. Consequently, users often need to increase their doses to achieve the same impact. Fentanyl induces cross-tolerance with all other opioids, meaning that after using fentanyl, other opioids will have a reduced effect.

The risk of fatal opioid overdoses significantly rises after a period of abstinence and relapse, primarily due to reduced tolerance. To account for this lack of patience, it is safer to administer only a fraction of the usual dosage when relapsing. Additionally, the environment in which the substance is used may influence opioid tolerance. In one scientific study, rats with the same history of heroin use were significantly more likely to overdose after receiving their dose in an environment not associated with the substance, as opposed to a familiar environment.

Dangerous Interactions

Warning: Many psychoactive substances that are reasonably safe when used alone can become dangerous, even life-threatening when combined with certain other substances. The following list highlights some known dangerous interactions, but it may not cover all possible ones.

Always conduct independent research (e.g., through Google, DuckDuckGo, or PubMed) to ensure the safety of combining two or more substances. Some interactions mentioned here are sourced from TripSit.

Alcohol – Both alcohol and fentanyl potentiate each other’s ataxia and sedation, potentially leading to unexpected loss of consciousness at high doses. Placing affected individuals in the recovery position is crucial to prevent aspiration of vomit due to excess sedation. Memory blackouts are also likely.

Amphetamines: Stimulants increase respiration rate, allowing for higher opioid doses than would otherwise be safe. If the stimulant’s effects wear off before the opioid, the latter may overwhelm the user and cause respiratory arrest.

Benzodiazepines: Combining benzodiazepines with fentanyl can result in central nervous system and respiratory depressant effects that may be additive or synergistic. This can rapidly lead to unconsciousness, and while unconscious, there is a risk of vomit aspiration. Memory loss or blackouts are common.

Cocaine: Stimulants like cocaine increase respiration rate, allowing for higher opioid doses than would otherwise be safe. If the stimulant’s effects wear off first, the opioid may overcome the user and cause respiratory arrest.

DXM – Combining DXM with opioids is generally considered toxic. It may result in central nervous system depression, difficulty breathing, heart issues, and liver toxicity. Additionally, taking DXM can slightly lower opioid tolerance, potentially leading to additional synergistic effects.

GHB/GBL – These substances intensely and unpredictably potentiate each other, rapidly leading to unconsciousness. While unconscious, there is a risk of vomit aspiration if the individual is not placed in the recovery position.

Ketamine: Both substances pose a risk of vomiting and unconsciousness if the user falls unconscious while under the influence; there is a severe risk of vomit aspiration if they are not placed in the recovery position.

MAOIs – Combining monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) with certain opioids has been associated with rare but severe adverse reactions. These interactions can manifest in two ways: an excitatory response and a depressive one. Symptoms of the excitatory response may include agitation, headache, sweating, hyperpyrexia, flushing, shivering, myoclonus, rigidity, tremors, diarrhea, hypertension, tachycardia, seizures, and coma, with potential fatalities.

MXE – MXE can potentiate the effects of opioids while increasing the risk of respiratory depression and organ toxicity.

Nitrous – Both nitrous and fentanyl potentiate each other’s ataxia and sedation, potentially leading to unexpected loss of consciousness at high doses. While unconscious, there is a risk of vomit aspiration. Memory blackouts are common.

PCP – PCP may reduce opioid tolerance, increasing the risk of overdose.

Tramadol: Combining tramadol with fentanyl may heighten the risk of seizures. Tramadol itself is known to induce seizures and may have additive effects on seizure threshold when combined with other opioids. Central nervous system- and respiratory-depressant impact may also be additively or synergistically present.

Grapefruit: Although grapefruit is not psychoactive, it may affect the metabolism of certain opioids. Substances like tramadol, oxycodone, and fentanyl are primarily metabolized by the enzyme CYP3A4, which grapefruit juice potently inhibits. This can delay the clearance of the drug from the body and increase its toxicity with repeated doses. Methadone may also be affected. Codeine and hydrocodone, on the other hand, are metabolized by CYP2D6. Individuals taking medications that inhibit CYP2D6 or those with a genetic mutation lacking the enzyme will not respond to codeine, as it cannot be metabolized into its active product, morphine.

Serotonin Syndrome Risk

Combining fentanyl with the following substances can lead to dangerously high serotonin levels, resulting in serotonin syndrome. This condition requires immediate medical attention and can be fatal if left untreated:

MAOIs – Such as banisteriopsis caapi, Syrian rue, phenelzine, selegiline, and moclobemide. Serotonin Releasers – Such as MDMA, 4-FA, methamphetamine, methylone, and αMT. SSRIs – Such as citalopram and sertraline. SNRIs – Such as tramadol and venlafaxine. 5-HTP

Legal status

Austria: Fentanyl is legally available for medical use under the AMG (Arzneimittelgesetz Österreich) but is considered illegal when sold or possessed without a prescription, classified as such under the SMG (Suchtmittelgesetz Österreich).

Australia: Fentanyl falls under Schedule 8 in Australia, allowing for its medical use. However, unauthorized possession, production, or supply of fentanyl is prohibited.

Canada: In Canada, fentanyl is classified as a Schedule I drug under the Controlled Drugs and Substance Act.

Germany: Fentanyl is categorized as a controlled substance under Anlage III of the BtMG in Germany. It can only be prescribed with a narcotic prescription form.

Netherlands: Fentanyl is listed as a List I substance under the Opium Law in the Netherlands.

Russia: Fentanyl is recognized as a Schedule II controlled substance in Russia.

Switzerland: Fentanyl is identified as a controlled substance mentioned explicitly in Verzeichnis A in Switzerland, and its medicinal use is allowed.

Turkey: Fentanyl is classified as a ‘red prescription’ only substance in Turkey and is illegal to sell or possess without a prescription.

United Kingdom: Fentanyl is considered a controlled Class A drug in the United Kingdom under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971.

United States: Fentanyl is categorized as a Schedule II controlled substance according to the Controlled Substance Act in the United States. Distributors of Abstral are required to implement an FDA-approved risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) program. Health insurers have also started to impose precertification and quantity limits for Actiq prescriptions.

FAQ

1. What is Fentanyl?

- Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid medication that is used for pain management, particularly for severe and chronic pain. It is one of the most potent opioids available and is many times stronger than drugs like morphine or oxycodone.

2. How is Fentanyl administered?

- Fentanyl can be administered in various ways, including as a patch applied to the skin (transdermal), tablets or lollipops, nasal sprays, injections, or as a sublingual tablet.

3. What are the medical uses of Fentanyl?

- Fentanyl is primarily prescribed by medical professionals to manage severe pain, often in situations such as surgery, cancer treatment, or for patients with chronic pain who require opioid therapy.

4. Is Fentanyl safe to use?

- Fentanyl is safe when used as prescribed by a healthcare provider. However, it is a potent medication and can be dangerous if misused or abused. It should only be taken under the guidance of a medical professional.

5. What are the risks associated with Fentanyl?

- The significant risks associated with Fentanyl use include respiratory depression (slowed breathing), overdose, and addiction. Overdosing on Fentanyl can be life-threatening.

6. Can I become addicted to Fentanyl?

- Yes, like other opioids, Fentanyl has a high potential for addiction. Even when used as prescribed, some individuals may develop physical and psychological dependence.

7. Are there any side effects of Fentanyl?

- Common side effects of Fentanyl use may include dizziness, nausea, vomiting, constipation, and drowsiness. More severe side effects can occur significantly if the medication is misused.

8. What precautions should I take when using Fentanyl?

- Always follow your healthcare provider’s instructions for Fentanyl use. Do not exceed the prescribed dose. Do not consume alcohol or other drugs while using Fentanyl, as it can increase the risk of dangerous side effects.

9. Is Fentanyl available without a prescription?

- No, Fentanyl is a prescription medication and should only be obtained through a licensed healthcare provider. Possessing Fentanyl without a prescription is illegal in many countries.

10. What should I do if I suspect an overdose of Fentanyl? – An overdose of Fentanyl can be life-threatening. If you suspect an overdose or encounter someone showing symptoms of an overdose (such as slow or irregular breathing, extreme drowsiness, or loss of consciousness), seek immediate medical help by calling emergency services.

11. How can I safely dispose of unused Fentanyl patches or medication? – Properly disposing of unused Fentanyl medication is crucial to prevent misuse. Follow local guidelines or consult with your pharmacist for safe disposal options, which often include designated drop-off locations or disposal kits.

12. Is Fentanyl the same as other opioids like heroin or morphine? – Fentanyl is chemically distinct from other opioids like heroin or morphine but acts on the same receptors in the brain and body. It is significantly more potent than many other opioids.

13. Can Fentanyl interact with other medications? – Fentanyl can interact with various medications, including certain antidepressants and sedatives. Inform your healthcare provider about all the medications you are taking to avoid potential interactions.

14. Are there alternatives to Fentanyl for pain management? – Yes, there are alternatives to Fentanyl for pain management, including other opioid medications and non-opioid pain relief options. Your healthcare provider can help determine the most appropriate treatment for your specific condition.

References

- Combining depressants can pose significant risks to individuals. Below are various sources and reports related to the use of depressants and their potential dangers:

- SUBLIMAZE Injection – Information available at this link: SUBLIMAZE Injection

- European Public Assessment Report (EPAR) for Instanyl – Detailed information can be found here: Instanyl EPAR

- Lazanda (Fentanyl) Nasal Spray CII – Refer to this source for insights: Lazanda Nasal Spray

- Fentanyl – Comprehensive information on Fentanyl can be accessed via Drugs.com

- NIOSH CDC Report – “Fentanyl: Incapacitating Agent,” a report from 2021, provides relevant data on Fentanyl.

- Mutschler, E., ed. (2001) – “Arzneimittelwirkungen: Lehrbuch der Pharmakologie und Toxikologie,” a textbook with extensive information.

- Fentanyl Fact Sheet – A concise fact sheet on Fentanyl is available at Drugs.com

- SAMHSA “Fact Sheet: Fentanyl-Laced Heroin and Cocaine” – A fact sheet discussing the dangers of Fentanyl-laced drugs: SAMHSA Fact Sheet

- NIDA Report – “Nearly half of opioid-related overdose deaths involve fentanyl,” retrieved on June 14, 2018.

- Hedegaard, H., et al. (December 2018) – “Drugs Most Frequently Involved in Drug Overdose Deaths: United States, 2011-2016.” A vital statistics report from the CDC.

- Stanley, T. H. (April 1992) – “The history and development of the fentanyl series” published in the Journal of Pain and Symptom Management.

- Black, J. (24 March 2005) – A personal perspective on Dr. Paul Janssen, as seen in the Journal of Medicinal Chemistry.

- FENTANYL AND ANALOGUES – Information related to Fentanyl and its analogs: Fentanyl and Analogs

- Subsys (Fentanyl Sublingual Spray) – Details about Subsys can be found at CenterWatch.

- INSYS Therapeutics Inc (2013) – Information on an open-label safety trial of Fentanyl Sublingual Spray for cancer pain treatment.

- UN Narcotic Drugs Report 2014 – Access the report here: Narcotic Drugs Report 2014

- DEA Report – Highlighting the surge in deaths from fentanyl-laced heroin.

- Sidner, R. E., Sara (2016) – Information about Prince’s accidental overdose of opioid fentanyl.

- Larsen, Rikke H., et al. (2003) – “Dermal Penetration of Fentanyl: Inter- and Intraindividual Variations” in Pharmacology and Toxicology.

- Varvel, J. R., et al. (1989) – “Absorption Characteristics of Transdermally Administered Fentanyl” in Anesthesiology.

- “Why Heroin Relapse Often Ends In Death” – An article by Lauren F Friedman in Business Insider.

- Siegel, S., et al. (23 April 1982) – “Heroin “Overdose” Death: Contribution of Drug-Associated Environmental Cues” in Science.

- Ershad, M., et al. (March 2020) – “Opioid Toxidrome Following Grapefruit Juice Consumption in the Setting of Methadone Maintenance” in the Journal of Addiction Medicine.

- Gillman, P. K. (2005) – “Monoamine oxidase inhibitors, opioid analgesics, and serotonin toxicity” in the British Journal of Anaesthesia.

- Poisons Standard February 2019 – Information about the Poisons Standard of February 2019.

- Consolidated Federal Laws of Canada – The Controlled Drugs and Substances Act in Canada.

- Various International Regulations – Including Russian, German, Swiss, and Turkish regulations related to controlled substances.

- Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 – The UK’s Misuse of Drugs Act from 1971.