Summary

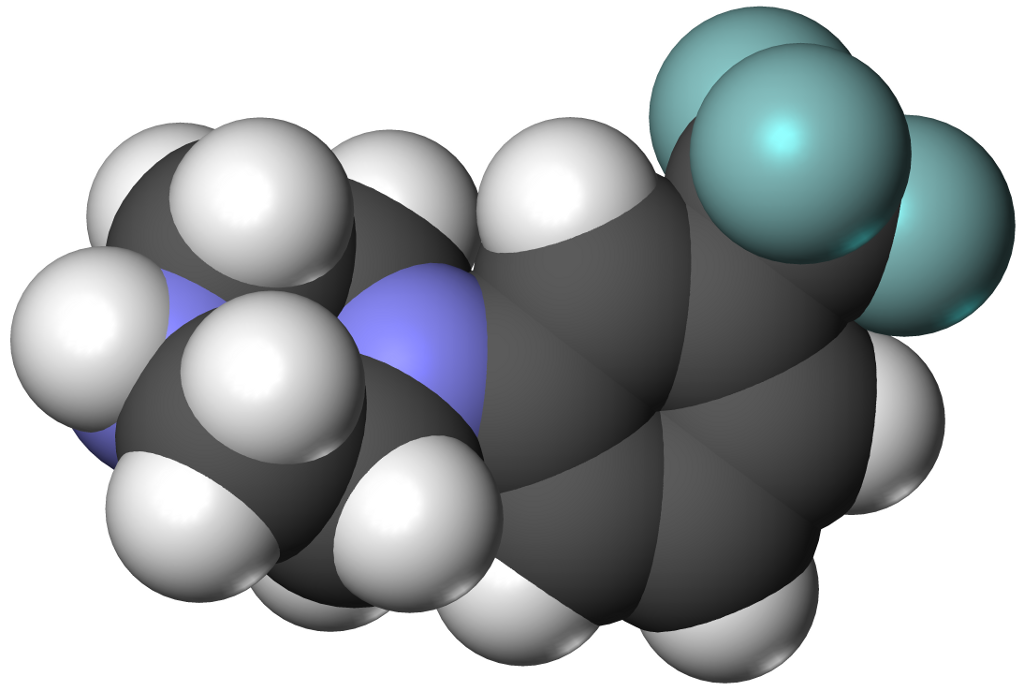

3-Trifluoromethylphenylpiperazine (TFMPP) belongs to the phenylpiperazine chemical class and is a substituted piperazine with recreational use. It is often marketed alongside benzylpiperazine (BZP) and similar compounds as a substitute for the illegal substance MDMA, commonly known as “Ecstasy.”

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name | |

| CAS Number | 15532-75-9 |

|---|---|

| PubChem CID | 4296 |

| ChemSpider | 4145 |

| UNII | 25R3ONU51C |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:83536 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID10165876 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.035.962 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C11H13F3N2 |

| Molar mass | 230.234 g·mol−1 |

Pharmacology

TFMPP exhibits a notable affinity for various serotonin receptors, specifically 5-HT1A (Ki = 288 nM), 5-HT1B (Ki = 132 nM), 5-HT1D (Ki = 282 nM), 5-HT2A (Ki = 269 nM), and 5-HT2C (Ki = 62 nM). At each of these receptor sites, TFMPP acts as a full agonist, with the exception of the 5-HT2A receptor, where it functions as a weak partial agonist or antagonist. In contrast to the piperazine compound meta-chlorophenylpiperazine (mCPP), TFMPP demonstrates minimal affinity for the 5-HT3 receptor (IC50 = 2,373 nM).

TFMPP also binds to the serotonin transporter (SERT) with an EC50 of 121 nM and triggers the release of serotonin. Significantly, it does not influence the reuptake or efflux of dopamine or norepinephrine.

Use and effects

TFMPP is seldom used on its own, primarily because it tends to decrease locomotor activity and induce aversive effects in animals, discouraging self-administration. This outcome may explain why the DEA opted not to classify TFMPP as a controlled substance permanently.

More commonly, TFMPP is co-administered with BZP, which serves as a releasing agent for norepinephrine and dopamine. The combination of BZP and TFMPP results in an increase in serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine levels, alongside serotonin agonist effects. Consequently, this drug blend generates effects that crudely resemble those of MDMA.

Side effects

The combination of BZP and TFMPP has been linked to a spectrum of side effects, encompassing insomnia, anxiety, nausea, vomiting, headaches, muscle discomfort resembling migraines, seizures, impotence, and, on rare occasions, psychosis. Additionally, users may experience a prolonged and unpleasant hangover effect. These side effects tend to intensify when the BZP/TFMPP combination is consumed alongside alcohol, particularly exacerbating symptoms such as headaches, nausea, and hangovers.

Determining which of these side effects can be attributed directly to TFMPP alone is challenging, as TFMPP is rarely marketed without the concurrent presence of BZP. Moreover, all the side effects mentioned are also associated with BZP, which has been sold as a standalone drug. Research into other related piperazine drugs, like mCPP, suggests that specific side effects such as anxiety, headaches, and nausea are common to all compounds within this class. Users report that pills containing TFMPP tend to induce more severe hangover effects compared to those holding only BZP. Furthermore, the drug can lead to sustained trembling in the body.

Legal status

Canada:

Since 2012, TFMPP has been categorized as a Schedule III controlled substance in Canada, rendering its possession a federal offense. Additionally, it has been included in Part J of the Food and Drug Regulations, which prohibits the substance’s production, export, or import.

China:

As of October 2015, TFMPP is classified as a controlled substance in China.

Finland:

TFMPP is scheduled as a prohibited psychoactive substance for the consumer market according to government decree.

Denmark:

Since December 3, 2005, TFMPP has been illegal in Denmark.

Japan:

In Japan, TFMPP and BZP became unlawful in 2003.

Netherlands:

TFMPP remains unscheduled in the Netherlands, with no specific restrictions noted.

New Zealand:

The New Zealand government, in line with the EACD’s recommendation, passed legislation to place BZP, TFMPP, mCPP, pFPP, MeOPP, and MBZP into Class C of the New Zealand Misuse of Drugs Act 1975. The sale of these substances became illegal in New Zealand as of April 1, 2008, following a prior amnesty period.

Sweden:

As of March 1, 2006, TFMPP is classified as a “dangerous substance” in Sweden.

Switzerland:

TFMPP became a controlled substance in Switzerland as of December 1, 2010.

United Kingdom:

In December 2009, TFMPP was designated as a Class C drug in the United Kingdom, alongside BZP.

United States:

TFMPP is not currently scheduled at the federal level in the United States; however, it was briefly emergency designed in Schedule I, a scheduling that expired in April 2004 and was not renewed. Nevertheless, some states like Florida have banned the drug through their criminal statutes, making its possession a felony.

Florida:

TFMPP is categorized as a Schedule I controlled substance in the state of Florida, rendering it illegal to purchase, sell, or possess in the form.

Texas:

TFMPP is controlled in Texas under Penalty Group 2 as a hallucinogenic substance, making its possession illegal in any quantity in the state.

FAQ

- What is TFMPP?

- TFMPP, or Trifluoromethylphenylpiperazine, is a chemical compound that belongs to the phenylpiperazine class of drugs. It has been used recreationally and is often found in combination with other substances.

- What are the recreational uses of TFMPP?

- TFMPP has been used recreationally, primarily in combination with substances like benzylpiperazine (BZP), as an alternative to the illegal drug MDMA, commonly known as “Ecstasy.”

- How does TFMPP affect the body?

- TFMPP acts on various serotonin receptors in the brain, affecting serotonin levels. It can lead to feelings of altered mood and perception.

- What are the common side effects of TFMPP use?

- Common side effects of TFMPP use may include insomnia, anxiety, nausea, vomiting, headaches, muscle aches, seizures, impotence, and, rarely, psychosis. TFMPP can also lead to a prolonged and unpleasant hangover effect.

- Is TFMPP legal?

- The legal status of TFMPP varies by country and region. It is classified as a controlled substance in some places, while in others, it remains unscheduled or not regulated. Always check your local laws and regulations.

- Is TFMPP safe to use recreationally?

- The safety of using TFMPP recreationally is a matter of concern. The potential for adverse side effects and interactions with other substances makes its recreational use risky. It is essential to exercise caution and be aware of the legal implications in your area.

- Are there any long-term health effects associated with TFMPP use?

- The long-term effects of TFMPP use are not well-documented due to its limited recreational use. However, given its impact on serotonin receptors, there may be potential risks to mental health and overall well-being with prolonged use.

- Can TFMPP be detected in drug tests?

- The detection of TFMPP in drug tests may vary depending on the specific test used and the substances being screened for. It’s important to note that testing methods may only sometimes specifically target TFMPP.

- What should I do if I suspect TFMPP use or abuse?

- If you suspect someone is using or abusing TFMPP or any other substances, it is advisable to seek help from a medical professional or a substance abuse counselor. Open and non-judgmental communication can be vital in helping someone address potential substance abuse issues.

- Where can I find more information about TFMPP and its legal status?

- To learn more about TFMPP and its legal status in your region, consult your local drug enforcement agencies or visit government websites dedicated to drug regulations and policies. It’s essential to stay informed and make responsible choices regarding substance use.

References

- Anvisa (2023-07-24). “RDC Nº 804 – Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial” [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 804 – Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 2023-07-25). Archived from the original on 2023-08-27. Retrieved 2023-08-27.

- “Ustawa z dnia 15 kwietnia 2011 r. o zmianie ustawy o przeciwdziałaniu narkomanii ( Dz.U. 2011 nr 105 poz. 614 )”. Internetowy System Aktów Prawnych. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- “4-(Piperazin-1-yl)-2-(trifluoromethyl)phenol”.

- “Erowid TFMPP Vault: Basics”. Erowid. Retrieved 2014-02-15.

- Schep LJ, Slaughter RJ, Vale JA, Beasley DM, Gee P (March 2011). “The clinical toxicology of the designer “party pills” benzylpiperazine and trifluoromethylphenylpiperazine”. Clin Toxicol. 49 (3): 131–41. doi:10.3109/15563650.2011.572076. PMID 21495881. S2CID 42491343.

- Baumann MH, Clark RD, Budzynski AG, Partilla JS, Blough BE, Rothman RB (March 2005). “N-substituted piperazines abused by humans mimic the molecular mechanism of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, or ‘Ecstasy’)”. Neuropsychopharmacology. 30 (3): 550–60. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300585. PMID 15496938. S2CID 24217984.

- Robertson DW, Bloomquist W, Wong DT, Cohen ML (1992). “mCPP but not TFMPP is an antagonist at cardiac 5HT3 receptors”. Life Sciences. 50 (8): 599–605. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(92)90372-V. PMID 1736030.

- Partilla JS, Dempsey AG, Nagpal AS, Blough BE, Baumann MH, Rothman RB (October 2006). “Interaction of amphetamines and related compounds at the vesicular monoamine transporter”. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 319 (1): 237–46. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.690.6669. doi:10.1124/jpet.106.103622. PMID 16835371. S2CID 22730478.

- Yarosh HL, Katz EB, Coop A, Fantegrossi WE (November 2007). “MDMA-like behavioral effects of N-substituted piperazines in the mouse”. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 88 (1): 18–27. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2007.06.007. PMC 2082056. PMID 17651790.

- Wilkins C, Girling M, Sweetsur P, Huckle T, Huakau J. “Legal party pill use in New Zealand: Prevalence of use, availability, health harms and ‘gateway effects’ of benzylpiperazine (BZP) and trifluorophenylmethylpiperazine (TFMPP)” (PDF). Centre for Social and Health Outcomes Research and Evaluation (SHORE). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-03-18. Retrieved 2007-04-14.

- “SOR/2012-65 March 30, 2012 Controlled Drugs and Substances Act”. Canada Gazette. Government of Canada. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- “关于印发《非药用类麻醉药品和精神药品列管办法》的通知” (in Chinese). China Food and Drug Administration. 27 September 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- “FINLEX ® – Säädökset alkuperäisinä: Valtioneuvoston asetus kuluttajamarkkinoilta… 1129/2015”.

- “FINLEX ® – Säädökset alkuperäisinä: Valtioneuvoston asetus kuluttajamarkkinoilta… 225/2017”.

- “FINLEX ® – Säädökset alkuperäisinä: Valtioneuvoston asetus kuluttajamarkkinoilta… 733/2021”.

- “Misuse of Drugs (Classification of BZP) Amendment Bill 2008”.

- “Erowid TFMPP Vault : Legal Status”. Erowid.

- “RO 2010 4099”. Fedlex. Retrieved 2022-08-16.

- “RO 2011 2595”. Fedlex. Retrieved 2022-08-16.

- “§1308.11 Schedule I.” Archived from the original on 2009-08-27. Retrieved 2014-12-17.

- “Scheduling Actions 2002”. U.S. Department of Justice, Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). Archived from the original on 2003-01-02.

- Florida Statutes – Chapter 893 – DRUG ABUSE PREVENTION AND CONTROL.