Contents

- 1 Summary

- 2 History

- 3 Marketing as dietary supplement

- 4 Pharmacology

- 5 Safety

- 6 Regulation

- 7 FAQ

- 7.1 1. What is Methylhexanamine?

- 7.2 2. Why is Methylhexanamine Controversial?

- 7.3 3. Where Has Methylhexanamine Been Banned?

- 7.4 4. What Are the Health Risks Associated with Methylhexanamine?

- 7.5 5. Is Methylhexanamine Used in Sports Enhancement?

- 7.6 6. Is Methylhexanamine Found in Dietary Supplements?

- 7.7 7. How Can I Ensure the Safety of Dietary Supplements?

- 7.8 8. Is Methylhexanamine Still Available on the Market?

- 7.9 9. What Should I Do If I Have Used Methylhexanamine-Containing Supplements?

- 7.10 10. Is Methylhexanamine Illegal?

- 8 References

Summary

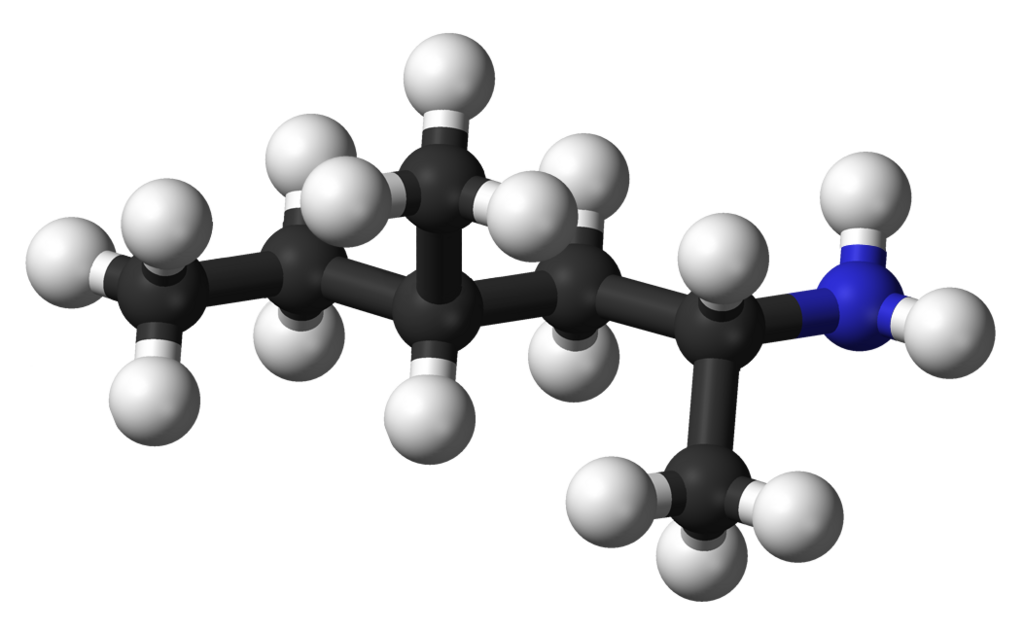

Methylhexanamine, also known as methylhexanamine, 1,3-dimethylamylamine, 1,3-DMAA, dimethylamylamine, and DMAA, was created and developed by Eli Lilly and Company. It was introduced as an inhaled nasal decongestant in 1948 and remained on the market until the 1980s when it was voluntarily withdrawn.

Since 2006, methylhexanamine has resurfaced under various names and has been widely sold as a stimulant or energy-boosting dietary supplement. Some marketing claims suggested it was akin to certain compounds found in geraniums. However, concerns about its safety have arisen due to a number of adverse events and, notably, at least five deaths linked to dietary supplements containing methylhexanamine. Consequently, it has been prohibited by numerous sports authorities and governmental agencies. Despite receiving multiple warning letters from the FDA, as of 2019, this stimulant continued to be available in sports and weight loss supplements.

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name | |

| CAS Number | 105-41-9 |

|---|---|

| PubChem CID | 7753 |

| ChemSpider | 7467 |

| UNII | X49C572YQO |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID60861715 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.002.997 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C7H17N |

| Molar mass | 115.220 g·mol−1 |

History

In April 1944, Eli Lilly and Company introduced a compound known as methylhexanamine, marketed under the brand name Forthane, as an inhaled nasal decongestant. However, in 1983, Lilly made a voluntary decision to withdraw methylhexanamine from the market.[11]: 12 This compound falls into the category of aliphatic amines. During the early 20th century, the pharmaceutical industry exhibited a keen interest in compounds of this class for their potential as nasal decongestants. This interest led to the introduction of methylhexanamine and four other similar compounds for nasal decongestant use: tuaminoheptane, octin (isometheptene), oenethyl (2-methylaminoheptane), and propylhexedrine. Octin and oenethyl eventually received approval for use in maintaining adequate blood pressure levels in patients undergoing anesthesia.

Marketing as dietary supplement

In 2006, Patrick Arnold reintroduced methylhexanamine as a dietary supplement, a move prompted by the final ban on ephedrine in the United States in 2005. Arnold brought it back to the market under the trademarked name Geranamine, which his company, Proviant Technologies, owned. Numerous supplements geared towards fat loss and workout energy, known as thermogenic or general-purpose stimulants, began incorporating methylhexanamine as an ingredient, often in combination with substances like caffeine. This combination mirrored the popular ephedrine and caffeine pairing.

Some methylhexanamine-containing supplements may mention “geranium oil” or “geranium extract” as the source of methylhexanamine. However, it’s important to note that geranium oils naturally lack methylhexanamine, and the methylhexanamine in these supplements is synthetically added material. Several studies have explored the potential presence of DMAA (methylhexanamine) in certain types of geraniums, but as of now, robust evidence supporting DMAA’s presence in plants remains limited.

The synthesis of methylhexanamine involves a chemical process where 4-methylhexan-2-one reacts with hydroxylamine, leading to the conversion of 4-methylhexan-2-one into 4-methylhexan-2-one oxime. This oxime is then reduced through catalytic hydrogenation, ultimately resulting in the production of methylhexanamine, which can be further purified via distillation.

Pharmacology

Methylhexanamine is an indirect sympathomimetic drug with various physiological effects, including the constriction of blood vessels impacting the heart, lungs, and reproductive organs. Additionally, it induces bronchodilation, inhibits intestinal peristalsis, and exhibits diuretic properties. Most research has focused on the drug’s pharmacological effects when administered through inhalation. Understanding its oral effects is largely derived from extrapolating data from similar compounds.[^97^]

According to a 2013 review, the anticipated pharmacological effects of oral intake include bronchodilation and nasal mucosa impact with a single oral dose ranging from 4 to 15 mg. Effects on the heart may occur with a single oral dose of about 50 to 75 mg, while blood pressure effects are expected with approximately 100 mg. Due to its prolonged half-life, repeated doses within 24 to 36 hours can lead to progressively stronger pharmacological effects (build-up).[^98^]

Detection in Body Fluids

Methylhexanamine can be quantified in blood, plasma, or urine through gas or liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. This analytical method serves to confirm poisoning diagnoses in hospitalized patients or provide evidence in medicolegal death investigations. Blood or plasma concentrations of methylhexanamine typically fall within the range of 10 to 100 μg/L for recreational users, exceeding 100 μg/L for intoxicated individuals, and surpassing 300 μg/L in cases of acute overdosage.

Safety

Toxicity and Health Implications

The LD50 for methylhexanamine, when administered intravenously, is 39 mg/kg in mice and 72.5 mg/kg in rats.

The FDA has cautioned that methylhexanamine narrows blood vessels and arteries, potentially raising blood pressure and increasing the risk of cardiovascular events, ranging from breathlessness and chest tightness to heart attacks. Several adverse events and at least five deaths have been associated with dietary supplements containing methylhexanamine. Reports have also linked secondary open-angle glaucoma to methylhexanamine supplementation.

In 2012, a review conducted by a panel convened by the U.S. Department of Defense to assess the potential ban of methylhexanamine supplements on military bases concluded that while existing evidence did not definitively establish a causal link between DMAA-containing substances and adverse medical events, there was a consistent indication that DMAA could impact cardiovascular function, similar to other sympathomimetic stimulants. The panel emphasized the need for further rigorous studies on DMAA’s safety, especially concerning concurrent use of other substances, underlying medical conditions, and high-frequency use. While the overall risk of DMAA-related events might be low, its widespread use among service members, often combined with other substances, could lead to significant consequences for some. As a result, the panel recommended continuing the prohibition of sales of DMAA-containing products on bases.

Deaths and Injuries

In 2010, a 21-year-old man in New Zealand experienced a cerebral hemorrhage after consuming 556 mg of methylhexanamine, caffeine, and alcohol. In Hawaii, health authorities linked cases of liver failure and one death to OxyElite Pro, a dietary supplement used for weight loss and bodybuilding.

The death of Claire Squires, a runner who collapsed near the finish line of the April 2012 London Marathon, was associated with methylhexanamine. The coroner suggested that methylhexanamine was “probably an important factor” during the inquest. Despite having been diagnosed with an irregular heartbeat and advised against methylhexanamine consumption, it is believed that she inadvertently ingested the substance through an energy drink. Subsequently, the formulation of the drink was changed to exclude methylhexanamine.

Regulation

Regulation and Bans

Methylhexanamine has faced stringent restrictions and bans in numerous countries and within various sports organizations due to significant safety concerns. Countries where its use is prohibited or heavily restricted include Australia, Brazil, Canada, Finland, New Zealand, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

In Sports

Many professional and amateur sports bodies, including the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), have banned methylhexanamine as a performance-enhancing substance. Athletes found to have used it have faced suspensions and other penalties:

- In March 2012, minor league baseball player Cody Stanley received a 50-game suspension for testing positive after using a dietary supplement.

- In July 2012, Welsh boxer Enzo Maccarinelli was banned for six months after testing positive for methylhexanamine[^34^].

- VFL player Matthew Clark received a two-year suspension after the substance was detected in his system following a game in 2011.

- In August 2012, minor league baseball player Marcus Stroman was suspended 50 games for testing positive for methylhexanamine.

- On August 8, 2013, US Weightlifter Brian Wilhelm accepted a nine-month suspension after testing positive for the drug.

- MotoGP rider Anthony West faced suspensions, starting with one month and later extended retroactively to 18 months, after testing positive for methylhexanamine.

- In December 2013, boxer Brandon Rios was suspended by the China Professional Boxing Association after testing positive.

- Three athletes at the 2014 Winter Olympics tested positive for methylhexanamine.

- In the 2015 Asian Cup, Iraqi player Alaa Abdul-Zahra faced an investigation over the illegal use of the drug.

- Algerian footballer Kheiredine Merzougi received a four-year ban from FIFA in March 2016.

- In November 2016, heavyweight boxer Bermane Stiverne was fined after testing positive for methylhexanamine.

- In 2017, the International Olympic Committee disqualified Jamaica’s 2008 gold-winning 4×100 men’s relay due to a positive test for methylhexanamine.

- AMA Supercross Championship rider Broc Tickle was provisionally suspended in April 2018.

- Filipino basketball player Kiefer Ravena faced suspension by FIBA in 2018 after testing positive for methylhexanamine.

- NASCAR crew chief Matt Borland was suspended in August 2019 after testing positive for DMAA; the suspension was lifted after completing NASCAR’s mandatory program.

Governmental Agencies

Governmental agencies in various countries have taken action to restrict or ban methylhexanamine:

- In 2010, the US military recalled all methylhexanamine-containing products from its exchange stores worldwide.

- In July 2011, Health Canada classified methylhexanamine as a drug requiring further approval and banned its sales.

- In June 2012, the National Food Agency of Sweden issued a warning about methylhexanamine products, resulting in a sales ban in some areas.

- In July 2012, the National Health Surveillance Agency of Brazil warned the public about the hazards of products containing methylhexanamine and updated its list of prohibited substances.

- Australia banned methylhexanamine in 2012, classifying it as a “highly dangerous substance” in New South Wales.

- In August 2012, the UK Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) ruled that the DMAA-containing sports supplement Jack3D was unlicensed and required removal from the UK market.

- In 2012, the New Zealand Ministry of Health banned the sale of methylhexanamine products, partly due to their recreational use as party pills.

- In April 2013, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) determined that methylhexanamine was potentially dangerous and did not qualify as a legal dietary supplement. The FDA issued warning letters to manufacturers and distributors of methylhexanamine-containing products.

FAQ

1. What is Methylhexanamine?

- Methylhexanamine, also known as DMAA (1,3-dimethylamylamine), is a synthetic compound that was originally developed as a nasal decongestant. It has stimulant properties and has been marketed as a dietary supplement and workout enhancer.

2. Why is Methylhexanamine Controversial?

- Methylhexanamine has raised controversy due to concerns about its safety and potential health risks. It has been associated with adverse events, including cardiovascular issues, and has led to bans and restrictions in various countries and sports organizations.

3. Where Has Methylhexanamine Been Banned?

- Methylhexanamine has been banned or heavily restricted in several countries, including Australia, Brazil, Canada, Finland, New Zealand, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Many sports bodies, like the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), have also prohibited its use.

4. What Are the Health Risks Associated with Methylhexanamine?

- The use of methylhexanamine has been linked to elevated blood pressure, cardiovascular events, liver failure, and even death. It can have various adverse effects on the heart, lungs, and other organs.

5. Is Methylhexanamine Used in Sports Enhancement?

- Yes, some athletes and bodybuilders have used methylhexanamine as a performance-enhancing substance. However, its use in sports is banned by many athletic organizations due to safety concerns and potential unfair advantages.

6. Is Methylhexanamine Found in Dietary Supplements?

- Yes, methylhexanamine has been marketed as dietary supplements and workout products. It has been listed under various names and is often claimed to boost energy and aid in fat loss. However, these supplements are a subject of regulatory scrutiny.

7. How Can I Ensure the Safety of Dietary Supplements?

- To ensure the safety of dietary supplements, it’s essential to be cautious when choosing products. Look for reputable brands and check for third-party testing or certifications. Consult with a healthcare professional before using any supplements, especially those containing controversial ingredients like methylhexanamine.

8. Is Methylhexanamine Still Available on the Market?

- While methylhexanamine-containing products faced regulatory actions and warnings from health authorities, they may still be available in some places. It’s important to stay informed about local regulations and exercise caution when considering their use.

9. What Should I Do If I Have Used Methylhexanamine-Containing Supplements?

- If you have used supplements containing methylhexanamine and have concerns about your health, seek medical advice. Discuss any symptoms or issues with a healthcare professional for proper evaluation and guidance.

10. Is Methylhexanamine Illegal?

- Methylhexanamine’s legal status varies by country and jurisdiction. In some places, it is banned or classified as a controlled substance, while in others, it may be available in limited forms. Always check your local regulations and laws regarding its use and availability.

References

- “DMAA: A Forbidden Stimulant” – United States Department of Defense: Operation Supplement Safety, issued by the U.S. Department of Defense on October 12, 2022, and retrieved on August 28, 2023, discusses the prohibited use of DMAA in supplements.

- “DMAA in Dietary Supplements” – On February 22, 2023, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) addressed the presence of DMAA in products marketed as dietary supplements, emphasizing its illegality and violation of marketing laws.

- “United States v. Hi-Tech Pharmaceuticals, Inc.” – According to Justia Law, a court ruling on August 30, 2019, stated that DMAA does not qualify as an ‘herb or other botanical,’ ‘constituent’ of such, or as generally recognized as safe by qualified experts, based on scientific procedures.

- “Withdrawal of Drug Applications” – In 1983, the Federal Register reported the withdrawal of drug applications related to DMAA by E. R. Squibb & Sons, Inc., under the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

- “Regulation in Brazil” – Anvisa, in a resolution dated July 24, 2023, outlined control measures for substances like DMAA in Brazilian Portuguese, officially published on July 25, 2023.

- “1,3-Dimethylpentylamine – Compound Summary” – The National Center for Biotechnology Information, USA, provided information on DMAA, dating back to March 26, 2005, and last retrieved on May 27, 2012.

- “DMAA as a Dietary Supplement Ingredient” – In July 2012, Archives of Internal Medicine published a study by Cohen discussing DMAA as a dietary supplement ingredient.

- “F.D.A. Warning on Workout Supplement” – On April 16, 2013, The New York Times reported on the FDA’s warning regarding workout supplements containing DMAA.

- “Products & Ingredients – DMAA in Dietary Supplements” – The Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN) addressed DMAA in dietary supplements in May 2019 on behalf of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

- “Prohibited Stimulants in Dietary Supplements” – In December 2018, JAMA Internal Medicine published a study by Cohen et al. on prohibited stimulants in dietary supplements after FDA enforcement action.

- “Department Of Defense: DMAA Safety Review Panel” – On June 3, 2013, a report by Col. John Lammie and others examined the safety of 1,3 Dimethylamylamine (DMAA).

- “Hidden Substance in a Chemist’s Product” – The Washington Post, on May 8, 2006, reported on a chemist’s product containing a hidden substance.

- “Under The Knife: 997” – On August 16, 2010, Baseball Prospectus featured an article by Carroll discussing DMAA.

- “Studies of Methylhexaneamine” – A study by Lisi, Hasick, Kazlauskas, and Goebel in 2011 examined methylhexaneamine in supplements and geranium oil.

- “Analysis of DMAA in Geranium Plants” – In 2012, Fleming et al. conducted an analysis of 1,3-DMAA and 1,4-DMAA in geranium plants using high-performance liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry.

- “DMAA as a Dietary Ingredient – Reply” – In April 2013, JAMA Internal Medicine published a reply by Cohen regarding DMAA as a dietary ingredient.

- “Methylhexaneamine Carbonate” – The entry in Marshall Sittig’s Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia, Second Edition, discussed methylhexaneamine in 1988.

- “Cerebral Hemorrhage Linked to DMAA” – In October 2012, Gee et al. reported a case of cerebral hemorrhage associated with recreational use of DMAA.

- “Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals” – The 10th edition of this publication in 2014 by Baselt includes information on DMAA.

- “Pharmacological Study of Alkoxyalkylamines” – In February 1953, Miya and Edwards conducted a pharmacological study involving certain alkoxyalkylamines.

- “FDA Challenges Marketing of DMAA Products” – On April 27, 2012, the FDA challenged the marketing of products containing DMAA due to potential health risks.

- “Secondary Open-Angle Glaucoma” – In March 2023, Balas and Mathew reported a case of secondary open-angle glaucoma related to dimethylamylamine supplementation.

- “Toxicity from DMAA Party Pills” – In December 2010, Gee et al. documented a case of toxicity associated with DMAA party pills.

- “Dietary Supplement Linked to Acute Hepatitis” – November 2013 saw a link between a dietary supplement and cases of acute hepatitis, as reported in JAMA.

- “Claire Squires’ Marathon Tragedy” – Claire Squires’ tragic death during the London Marathon was linked to DMAA, as reported by BBC News in January 2013.

- “WADA’s Prohibited List” – In September 2009, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) included DMAA on its prohibited list.

- “IAAF’s Jamaica Drug Ruling” – The IAAF awaited a drug ruling related to Jamaica in August 2009.

- “Positive Tests in Cycling” – Positive tests involving DMAA occurred in cycling, including Rui Costa and others in 2010.

- “Minor Leaguer’s Suspension” – In November 2011, a minor league baseball player received a 50-game suspension for DMAA use.

- “Doping Violation in Aquathlon and Duathlon” – In February 2012, doping violations involving DMAA affected aquathlon and duathlon athletes.

- “Suspension of Cody Stanley” – Cody Stanley, a minor league baseball player, faced suspension due to DMAA in 2012.

- “Enzo Maccarinelli’s Suspension” – Enzo Maccarinelli received a six-month suspension in July 2012 for DMAA use.

- “Ahmed Saad’s Two-Year Ban” – St Kilda’s Ahmed Saad faced a two-year ban in July 2013 due to DMAA use.

- “Marcus Stroman’s Suspension” – In February 2013, Jays prospect Marcus Stroman received a 50-game suspension for DMAA use.

- “US Weightlifting Athlete’s Sanction” – A U.S. weightlifting athlete, Wilhelm, accepted a sanction for DMAA-related anti-doping rule violation on August 8, 2013.

- “Anthony West’s Loss of Results” – Anthony West lost his results after an anti-doping appeal related to DMAA.

- “Brandon Rios’ Suspension” – Brandon Rios faced suspension by CPBO until April 24th, as reported on December 16, 2013.

- “Evi Sachenbacher-Stehle’s Case” – In February 2014, Evi Sachenbacher-Stehle and William Frullani faced repercussions related to DMAA.

- “Expulsion of Two Athletes” – In February 2014, two athletes were expelled from competition due to doping violations involving DMAA.

- “Ineligible Iraq Player” – Iran protested the use of an ineligible Iraq player in an Asian Cup quarter-final match.

- “Doping on Algeria’s Football Pitches” – Doping incidents involving DMAA were reported on Algeria’s football pitches.

- “Four-Year Bans for Algerian Players” – FIFA extended four-year bans worldwide for three Algerian players in March 2016.

- “Stiverne Tests Positive” – Bermane Stiverne tested positive for a banned substance, affecting his fight against Alexander Povetkin in 2016.

- “Usain Bolt Loses Olympic Gold” – Sprinter Usain Bolt lost one Olympic gold medal due to a teammate’s failed dope test.

- “Provisional Suspension of Broc Tickle” – Broc Tickle faced a provisional suspension due to DMAA use.

- “FIBA’s Ban on Ravena” – FIBA imposed an 18-month ban on Ravena for a doping violation involving DMAA in May 2018.

- “Matt Borland’s Suspension” – Matt Borland, a crew chief, was suspended after a failed drug test attributed to diet coffee.

- “Reinstatement of Matt Borland” – Matt Borland was reinstated after completing the Road to Recovery Program.

- “DMAA Products Removed from Base Shelves” – DMAA products were removed from military base shelves, as reported on January 24, 2013.

- “DMAA Reformulation by Brands” – DMAA-containing brands started reformulating products without DMAA in May 2012.

- “Warning About DMAA-Containing Supplements” – A warning about DMAA-containing supplements was issued in August 2012, mentioning their illegal status.

- “Supplement Alert in Brazil” – In July 2012, the Brazilian National Health Surveillance Agency (ANVISA) issued an alert about the risks of consuming DMAA-containing supplements.

- “Brazilian Regulation – RDC no. 37” – ANVISA’s Resolution of Collegiate Board (RDC) no. 37 in July 2012 detailed the regulatory measures concerning DMAA.

- “DMAA Banned in Australia” – DMAA in workout drinks was made illegal in Australia in August 2012.

- “MHRA’s Removal of Sports Supplement” – The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) announced the removal of a sports supplement used by international athletes in January 2013.

- “Temporary Class Drug Notice in New Zealand” – New Zealand’s Ministry of Health announced a Temporary Class Drug Notice related to DMAA on March 8, 2012.

- “Concerns About New Pill Ingredient” – In October 2008, concerns were raised about a new pill ingredient, indicating potential issues with DMAA.

- “Party Pill Inventor Supports Restriction” – The inventor of party pills supported restrictions on DMAA, as reported in November 2009.

- “FDA Warns About DMAA” – On April 11, 2013, the FDA issued a warning about the health risks associated with DMAA-containing products.

- “OxyElite Pro Recall” – On November 10, 2013, the FDA recalled OxyElite Pro dietary supplements by USP Labs due to links with liver illnesses.